Illustration by Stephanie Dalton Cowan © 2017

When Amy Berman, BSN, LHD (aged 58), stood in front of the mirror to perform a routine breast self-exam and saw redness and dimpling on her right breast, she feared they were the telltale signs of inflammatory breast cancer. “I have never self-diagnosed myself before, but I had recently read an article on inflammatory breast cancer and knew the symptoms. I also knew the cancer had a very poor prognosis,” said Ms. Berman.

Hoping she caught the cancer at its earliest stage, when aggressive treatment might render a cure, she was shocked to learn the cancer had already metastasized to her lower spine. She was now facing stage IV inflammatory breast cancer, a disease from which many patients have a likely life expectancy of less than 5 years.

Quality and Quantity of Life

Reluctant to endure curative-intent therapy for an incurable cancer, after a conversation with her oncologist, Ms. Berman opted to have palliative care (which emphasizes quality of life and should involve care from specialized professionals) and an anticancer treatment regimen that included letrozole, to tamp down the hormones fueling her cancer, and infusions of zoledronic acid, to keep her bones strong and her cancer manageable without leaving her debilitated and unable to continue her work as Senior Program Officer at the John A. Hartford Foundation in New York, or spend quality time with family and friends. Today, Ms. Berman is receiving third-line therapy with palbociclib (Ibrance) for her advanced breast cancer.

“I didn’t expect to live a long life and wanted to have a life that was as good as possible for as long as possible,” explained Ms. Berman. “Having time with my family, time with my friends, and as much time feeling as well as possible are my primary goals.”

Palliative care is my best friend. I don’t know what I would have done without it.— Amy Berman, BSN, LHD

Tweet this quote

Determined to ensure she was doing everything possible to stay ahead of her cancer and hoping there was perhaps a viable new treatment on the horizon, Ms. Berman sought a second opinion from a top expert in breast cancer. The conversation left her even more convinced that palliative care was the right decision.

“The second oncologist never asked me one question about my goals of treatment or my preferences and wishes for my life. Rather, he proposed the standard aggressive course of treatment: intensive rounds of chemotherapy, followed by a mastectomy, radiation, and more intensive chemotherapy. There was nothing in his plan suggesting a different outcome, and it probably meant I would spend multiple visits in the hospital from the surgery and treatment side effects. I knew what he was suggesting would not offer me any real benefit and only result in compromising the quality of my remaining life,” said Ms. Berman.

Life Extending, Not Life Limiting

Ms. Berman’s decision for a gentler, less aggressive course of therapy for her advanced cancer has resulted in not just more quality of time but more quantity of time as well. Despite further metastasis to her ribs since her diagnosis in 2010, which was remedied by a single, larger dose of radiation, Ms. Berman feels well and continues to live and work at the same breakneck pace she always has. There is, in fact, evidence that palliative care can extend some patients’ lives.1,2

National Consensus Project Definition of Palliative Care

“Palliative care means patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and [facilitating] patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.”

Source: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care.9

When Ms. Berman was diagnosed with terminal cancer she immediately documented her wishes for end-of-life care in an advance care directive—something fewer than 50% of severely or terminally ill patients do.3 She made sure the directive was embedded into her electronic medical record and gave copies of the document to her mother, whom she had designated as her health-care proxy; her oncologist; her primary care physician; members of her palliative care team; and the hospital. She also keeps a copy with her to ensure there is no confusion about her desire to die at home; to remain free of pain; and not to be given life-sustaining procedures, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and artificial nutrition and hydration, when her quality of life deteriorates.

Suing for Not Allowing Patients to Die

Although Ms. Berman is doing everything possible to make certain physicians and hospital and emergency staff are aware of her end-of-life wishes—between 65% and 76% of physicians are unaware if their patients have an advance directive4—her efforts are still no guarantee they won’t be ignored or overridden during a medical crisis.

A recent story5 in The New York Times showed that even with an advance directive or the more comprehensive Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) forms in place, often instructions against life-sustaining interventions are violated. And the family members of these patients are turning to the courts for justice—and compensation—and they are winning.

Appellate courts are now declaring it is wrong to resuscitate a patient if the patient doesn’t want to be resuscitated.— Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD

Tweet this quote

Although, historically, courts have been reluctant to take on lawsuits for failing to let a patient die, that sentiment is changing.6 “Appellate courts are now declaring it is wrong to resuscitate a patient if the patient doesn’t want to be resuscitated,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, Director of the Health Law Institute and Professor of Law at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota. “And that’s helpful because it was not 100% clear in the past that that was the case. Physicians would often say, ‘I saved the patient’s life. How could I get into trouble for that?’”

And families feel a certain duty to hold health-care providers accountable if they go against their loved one’s advance directive and are now more willing to take legal action against physicians and medical institutions charging negligence and intentional infliction of emotional, physical, and financial distress, according to Dr. Pope.

Ms. Berman agrees. “I’ve instructed my family to sue my hospital if my wishes are not followed, because it is a preventable harm, and health-care providers should be respectful of patients’ wishes,” she explained.

Although it is difficult to know how many cases are being brought to trial and won, because the cases are often settled privately or through arbitration, courts are increasingly imposing penalties on health-care providers who deliberately or negligently disregard advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders. “We are only seeing the lawsuits that are public, which is just the tip of the iceberg of the lawsuits filed,” said Dr. Pope.

GUEST EDITOR

Addressing the evolving needs of cancer survivors at various stages of their illness and care, Palliative Care in Oncology is guest edited by Jamie H. Von Roenn, MD. Dr. Von Roenn is ASCO’s Vice President of Education, Science, and Professional Development.Telling Patients the Whole Truth

However, the problem of potential liability for physicians and medical institutions is not limited to unwanted medical treatment. Giving patients insufficient information about a treatment that may not prolong life more than a few weeks may also put physicians in legal jeopardy, according to Dr. Pope. “A big, big problem in oncology is unwanted treatment in a different sense. It’s not unwanted because the patient said he didn’t want it and the treatment was given anyway in a concrete violation of his preferences. In oncology, the problem is patients are often not adequately educated about the risks, benefits, costs, and alternatives to a treatment that is being proposed. Often, that treatment has only a small chance of prolonging patients’ lives for a few weeks or at all. In a way, it is misleading patients into thinking they have more time,” said Dr. Pope. (See “Ensuring Advance Directives Are Followed and Lawsuits Are Avoided,” on page 61.)

More Effective Patient Communication

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology examining how the timing of end-of-life discussions affects patients’ decisions about care in the last days of their lives found that initiating these discussions before the last month of life resulted in less frequent use of chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life, lower use of acute or intensive care in the last 30 days of life, and increased use of hospice care.7

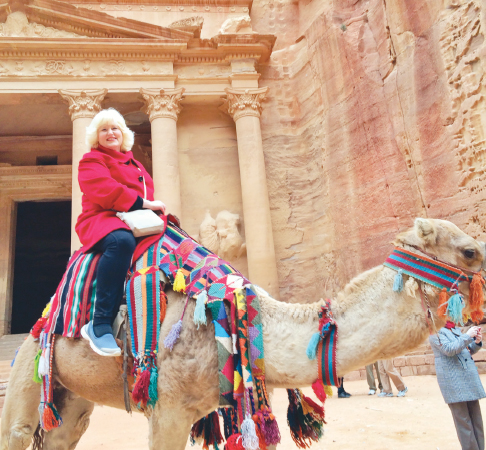

Diagnosed with stage IV inflammatory breast cancer in 2010, Amy Berman opted for palliative care rather than aggressive treatment to preserve her quality of life for as long as possible. Here she is on a visit to the ancient city of Petra, Jordan, in 2016. Today, she continues to feel well and lives and works at the same breakneck pace she always has.

National clinical practice guidelines recommend that conversations about palliative care (which include, but are not limited to, end-of-life issues) begin soon after a patient is diagnosed with a life-limiting or advanced cancer, to ensure care aligns with the patient’s goals and preferences and identifies appropriate quality of life–promoting interventions.2,8,9 Those guidelines also concur with ASCO’s statements and guidelines for individualized care for patients with advanced cancer and their families, which includes an assessment of the patient’s and family’s symptoms and coping needs, goals, and preferences for care and decision-making throughout the trajectory of illness; this may include psychosocial and/or spiritual support. Patients and clinicians may discuss anticancer therapy only when it is likely to result in significant clinical benefit,2,10 The priority throughout the course of disease, according to ASCO, should be on “enhancing patients’ quality of life.”

Studies show that patients with advanced cancer want their oncologists to discuss their advance care plans with them, yet fewer than half of those patients have that conversation. The reasons are many, including the difficulty oncologists have in initiating conversations about noncurative options with their patients, the fear such a conversation will lead patients to abandon hope, and the worry that the news will adversely affect the patient and lead to a worse outcome. Patients may also be hesitant to broach the subject with their oncologists over concern it may be interpreted as an expression of disappointment in their oncologist and in the care they received.11

To remove some of these barriers preventing comprehensive end-of-life conversations, ASCO has developed a decision-making guide: Advanced Cancer Care Planning: A Decision-Making Guide for Patients and Families Facing Serious Illness (www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/advanced_cancer_care_planning.pdf). The guide provides resources to help patients, their families, and caregivers communicate more directly about end-of-life care options with their oncologists and information on choosing a health-care proxy and completing advance directives.

Several years ago, Robert M. Arnold, MD, Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Director of the Institute for Doctor-Patient Communication at the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues launched VitalTalk (vitaltalk.org), a nonprofit educational program for physicians that offers both online courses and in-person workshops to improve effective and honest conversations between clinicians and patients about serious illness and end-of-life preferences. The program’s website also includes short 2- to 3-minute videos that illustrate enactments with patients on delivering difficult news, addressing goals of care, and building family relationships to promote patient-centered care, as well as establishing rapport with patients, balancing hope and realism, and helping patients accept their terminal illness.

“We have set up the perfect storm of misunderstanding the limitations of what medicine can and can’t do.”— Robert M. Arnold, MD

Tweet this quote

“We live in a society in which cancer is viewed as a war, and patients should never surrender. And that sense of perseverance is encouraged by some cancer centers’ advertisements that seem to promise miraculous cures, so we have set up the perfect storm of misunderstanding the limitations of what medicine can and can’t do,” said Dr. Arnold. “If you make talking about advance directives a normal part of your conversation with patients, most patients will be okay with it, because in most cases, they have already thought about what they would do if their situation worsens. Physicians should talk with patients with advanced cancers about what they would like to do if their cancer gets worse and what their hopes and fears are if their lifespan is limited. And that means oncologists need to be okay with their patients being sad, and that is really hard for many of us.”

Amy Berman considers the conversation she had with her oncologist about her treatment preferences following her diagnosis of incurable breast cancer as lifesaving. It allowed her to have a chance at living the best life possible for as long as possible.

“My professional training and my work in the field of palliative care helped me to understand how important it was for me to integrate palliative treatment into my goals of care after my diagnosis of terminal breast cancer,” said Ms. Berman. “And it has allowed me to have a great life for 7 years. Palliative care is my best friend. I don’t know what I would have done without it.” ■

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Pope reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Arnold is on the board of VitalTalk, a not-for-profit company.

REFERENCES

1. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al: Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010.

2. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al: Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2016.

3. Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, et al: Decision aids for advance care planning: An overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med 161:408-418, 2014.

4. Kass-Bartelmes BL, Hughes R: Advance care planning: Preferences for care at the end of life. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 18:87-109, 2004.

5. Span P: The Patients Were Saved. That’s Why the Families Are Suing. The New York Times, April 10, 2017.

6. Pope TM: Legal briefing: New penalties for ignoring advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders. J Clin Ethics 28:74-81, 2017.

7. Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al: Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 30:4387-4395, 2012.

8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Palliative Care National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available from www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed June 22, 2017.

9. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Third Edition. Available from www.hpna.org/multimedia/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2017.

10. Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:755-760, 2011.

11. Gesme DH, Wiseman M: Advance care planning with your patients. J Oncol Pract 7:e42-e44, 2011.