Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is one of the success stories among the hematologic malignancies. Now, with decades of data informing its management, it is time to change some of the practices to which clinicians have become accustomed, said leukemia expert Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, FASCO, Professor and former Chair of the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Kantarjian described his own approaches at the 2025 Debates and Didactics in Hematology and Oncology conference, sponsored by Emory Winship Cancer Institute.1

Now, 30% to 50% of patients [with CML] can, at some point in time, discontinue treatment, and their disease will not come back.…— HAGOP M. KANTARJIAN, MD, FASCO

Tweet this quote

“Today, CML is an indolent disease where patients are expected to live their normal lives—provided they take a BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor on a daily basis, they can afford treatment, they comply with treatment, and they change the tyrosine kinase inhibitor at the first sign of resistance (which I define as BCR::ABL1 transcript levels [on International Scale] > 1%. It’s as simple as that,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

“Now, 30% to 50% of patients can, at some point in time, discontinue treatment, and their disease will not come back.… If you can get the patient into a deep molecular response—at least a 4-log reduction of the disease—and if it lasts for 2 to 5 years—then there is the probability of a treatment-free remission. I call this a ‘molecular cure,’” he said.

This success is the result of the development of multiple BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor asciminib was the sixth to be approved, and four new tyrosine kinase inhibitors may become available within 5 years. The “third-generation” investigational tyrosine kinase inhibitors are being divided into two categories: those similar to ponatinib—still affecting the ABL1 kinase domain (olverembatinib, ELVN-001)—and those similar to asciminib—specifically targeting the ABL1 myristoyl pocket—being called STAMP inhibitors (TGRX-678, TERN-701).

“These four novel agents have been difficult to develop, because it’s become rare to see a patient with truly resistant disease. The studies are therefore accruing mostly patients failing to respond to treatment because of side effects,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

Reassessing Established Treatment Traditions

The initial recommendations and guidelines for using tyrosine kinase inhibitors “have not stood the test of time” with longer follow-up, according to Dr. Kantarjian. He offered his thoughts on some of the traditional practices:

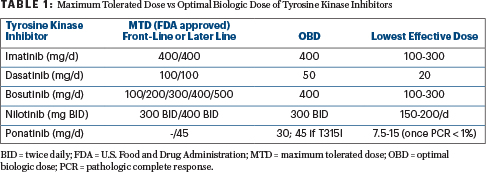

- Use tyrosine kinase inhibitors at the maximum tolerated dose (MTD): It is not necessary to use the maximum tolerated dose or the dose approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The optimal biologic dose (which is typically lower) may be as effective and less toxic in both the front-line and later lines of treatment. For example, this would be 50 mg/day for dasatinib and 15 to 30 mg/day for ponatinib.

- Use the best tyrosine kinase inhibitor first and ignore the cost: Generic imatinib is now available at $500 a year, and generic dasatinib at 50 mg/day costs about $3,800 a year. Thus, costs of front-line therapy can be contained.

- The failure rate of front-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors is about 40%: This is not true. A 2017 study from Germany found the rate of treatment resistance to be only 10% over 10 years.2

- In the setting of tyrosine kinase inhibitor toxicity, switch the tyrosine kinase inhibitor: Concerns that dose reductions would result in reduced efficacy were not established. Unless the toxicity is prohibitive, it is better to reduce the dose than to switch the tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

- Pursue treatment-free remission aggressively by rotating tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Changing the tyrosine kinase inhibitor may harm patients in the pursuit of a pathologic complete response–negative state that may never be achieved. It is more advisable to continue the patient on the tyrosine kinase inhibitor as long as the pathologic complete response level is < 1%.

Front-Line Aims in CML

The first aim is to improve survival, although in a disease with a relative overall survival rate of 92%, this is unlikely; novel third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors might change this. The second aim is to improve the rate of durable deep molecular responses to increase the rate of treatment-free remission. The third aim is to reduce short-term and long-term side effects of treatment. Finally, the cost of front-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors must be contained, Dr. Kantarjian said.

“If you’re aiming for a survival benefit, any of the front-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors can produce that,” he maintained. Data from MD Anderson and elsewhere (Germany) have shown the 10-year CML-relative survival rate to be above 90%.

Unless the toxicity is prohibitive, it is better to reduce the dose than to switch the tyrosine kinase inhibitor.— HAGOP M. KANTARJIAN, MD, FASCO

Tweet this quote

Enthusiasm to prescribe the newest agent asciminib might be tempered by the lack of significant improvement over the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the registrational trial’s primary endpoint, major molecular response at 48 weeks,3 Dr. Kantarjian added. “For any tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is expensive, we have to provide something better than provided by imatinib or dasatinib; in the long run, that should be either better survival or a higher rate of treatment-free remission,” he said.

In the front-line CML setting, Dr. Kantarjian typically uses these tyrosine kinase inhibitors in these doses: imatinib (400 mg/day); dasatinib (50 mg/day); nilotinib (300 mg twice daily; dose-reduced to 150 mg twice daily or 200 mg daily when major molecular response is achieved); bosutinib (400 mg/day, in a dose-escalated fashion to avoid gastrointestinal toxicity); and asciminib (80 mg/day).

Optimal Biologic Dose

Dr. Kantarjian elaborated on using the optimal biologic dose of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor rather than the maximum tolerated or FDA-approved dose—a form of dosing that was developed to allow for long-term dosing and avoidance of toxicity. For most drugs, the optimal biologic dose is established in phase I/II trials, but for dasatinib, the 50-mg/day dose was developed based on clinical observation. “Long-term follow-up has shown that 50 mg/day of dasatinib yields outstanding results in terms of survival and achievement of complete molecular response,” he pointed out.

In a 2023 study of 83 newly diagnosed patients treated with low-dose dasatinib for 5 years, the 5-year overall survival rate was 95% (two deaths were unrelated to CML); the major molecular response rate was 95% at 5 years; no patient developed accelerated-phase or blast-phase CML; and just five patients (6%) switched to another tyrosine kinase inhibitor for possible suboptimal response or resistance.4

Still, Dr. Kantarjian noted, many oncologists have been hesitant to use low-dose dasatinib without evidence from a randomized controlled trial. This has now been provided from a study from India of 120 newly diagnosed patients; no differences in efficacy were observed between the 70-mg/day and the 100-mg/day doses.5 Toxicities, on the other hand, such as pleural effusions, were significantly fewer with 70 mg/day.

Table 1 shows the differences between the maximum tolerated or FDA-approved dose and the optimal biologic dose. Dr. Kantarjian typically tries the optimal biologic dose first.

Front-Line Therapy

Dr. Kantarjian cited a 2017 study from Germany that informed much of the current knowledge about the use of BCL::ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of CML today.2 The study followed 1,551 newly diagnosed patients treated with various imatinib-based regimens. At 10 years, the relative overall survival rate was 92% (“near normal”), the rate of blast phase was 5.8%, and the rate of resistance was about 10% (or 1% per year). Approximately 26% of patients switched from imatinib to a second tyrosine kinase inhibitor, but this was mostly because of toxicity; the toxicity rate was also low, about 1.5% per year.

Is there a “best” front-line therapy? Dr. Kantarjian would opt for imatinib if survival is the endpoint; at $500/year over 30 years, the estimated lifetime treatment cost is $15,000. Generic dasatinib at 50 mg/day is a good choice if earlier treatment-free remission is the endpoint, and a cost of about $3,500 a year is acceptable to many patients, he said, adding that in high-risk patients, dasatinib at 50 to 100 mg/day is recommended. Once a good molecular response is achieved, any tyrosine kinase inhibitor can be dose-reduced.

Elaborating on achieving treatment-free remission, Dr. Kantarjian emphasized the importance of remaining on the same tyrosine kinase inhibitor long term and being “patient.” As a number of studies have shown, treatment-free remission may be achieved in about half the patients treated for at least 2 years before stopping, but by treating for at least 5 years and achieving more durable deep molecular responses, treatment-free remission rates increasingly climb.

“At MD Anderson, we have treated for even longer and have shown in follow-up that if you wait for 5 years or more for a sustained, or durable, deep molecular response, then stop therapy, the potential for a molecular cure goes up to 80%. This is what we advise patients today,” he reasoned.

When to Switch the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor

In the setting of toxicity, Dr. Kantarjian reduces the tyrosine kinase inhibitor dose rather than switching the tyrosine kinase inhibitor unless there is high potential for irreversible organ damage. Such situations include recurrent pleural effusions, pulmonary hypertension, arterio-occlusive or vaso-occlusive events, pancreatitis, certain neurologic problems, serious immune-related events (eg, pericarditis, myocarditis, hepatitis, nephritis), and bosutinib-associated enterocolitis.

Switching the tyrosine kinase inhibitor is necessary for CML-resistant disease, which is indicated by a pathologic complete response level > 1% after at least 1 year of treatment. Dr. Kantarjian noted this tends not to be necessary in older patients with CML, however, as they may still live their normal lives in chronic phase.

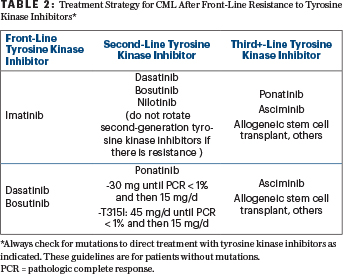

When switching agents is warranted, any second- or third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor is acceptable (Table 2), but Dr. Kantarjian now advocates for trying ponatinib or asciminib in patients who fail to respond to a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. “With asciminib, the data look excellent in terms of a high molecular response rate with minimal side effects,” he said. “Ponatinib is potent but toxic, so I would use it at 30 mg and reduce to 15 mg once patients achieve complete molecular response.”

Finally, Dr. Kantarjian will consider allogeneic stem cell transplant, especially for patients with multiple treatment failures because of either resistance or toxicities. “This one-time therapy is underutilized, highly curative, and cost-effective,” he noted. If a transplant cannot be considered, he hopes to enroll these patients on trials of new tyrosine kinase inhibitors in development.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Kantarjian has received honoraria and served as a consultant or advisor to AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage Pharma, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, KAHR Medical, Novartis, Pfizer, Shenzhen TargetRx, Stemline Therapeutics, and Takeda Pharmaceutical; and has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage Pharma, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, ImmunoGen, and Novartis.

REFERENCES

- Kantarjian H: Contemporary management of CML. 2025 Debates and Didactics in Hematology and Oncology. Presented July 24, 2025.

- Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saußele S, et al: Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-Year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia 31:2398-2406, 2017.

- Hochhaus A, Wang J, Kim DW, et al: Asciminib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 391:885-898, 2024.

- Gener-Ricos G, Haddad FG, Sasaki K, et al: Low-dose dasatinib (50 mg daily) frontline therapy in newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: 5-Year follow-up results. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 23:742-748, 2023.

- Satadeve P, Gupta A, Kachhwaha A, et al: Comparison of molecular response and safety of lower dose (70 mg) versus standard dose (100 mg) of generic dasatinib in newly diagnosed patients with CML-CP: Randomised controlled study from India. European Hematology Congress 2025. Abstract S168. Presented June 12, 2025.