George H. Beauregard, DO

My twin brother and I were adopted at 18 months old, so I don’t know the medical history of our biological parents and family. But for certain, cancer has played an integral—and heartbreaking—role in my life. Both of my adoptive parents were diagnosed with genitourinary cancers at relatively early ages. My mother died of complications related to uterine cancer when she was 53, and my father was diagnosed with kidney cancer when he was in his mid-50s. He later died of dementia when he was 86.

I was diagnosed with stage 3 bladder cancer, in 2005, when I was 49. I can’t help but wonder if environmental factors were involved in contributing to our family’s early-onset cancers, since there couldn’t be an inherited genetic risk. My twin brother’s death at age 31 was unrelated to cancer.

I didn’t know it then, but my greatest anguish from cancer was yet to come.

Deciding on the Best Course of Treatment

As a physician, I recognized immediately when I urinated a drop of blood that I could have cancer, but I quickly dismissed the thought. I knew bladder cancer usually occurs in people older than age 65, and I wasn’t experiencing any other symptoms of the disease, so it was easy for me to initially push the thought out of my mind. Plus, having a busy life practicing medicine and raising a young family provided enough distractions to steer me away from worrying about cancer.

Eventually, however, I could no longer ignore the increasing amounts of blood in my urine. An ultrasound showed a mass in my bladder, and a cystoscopy confirmed a cancer diagnosis. Additional tests found the disease had progressed to stage 3.

Because all of the research data available 20 years ago in the treatment of this cancer were based on protocols for older men, I sought multiple opinions before I committed to a therapy regimen. I met with three surgeons who agreed I needed to have a radical cystectomy, as well as the removal of a segment of my small intestine to construct a neobladder. But when I consulted with three medical oncologists, they each gave a different suggestion for which cisplatin-based systemic chemotherapy regimens might be most effective and when best to use them: before or after surgery.

Since there was no clear evidence of which strategy had the highest probability of even giving me a 50% chance of surviving the cancer for 5 years, I threw a dart at a dart board with the different scenarios and chose neoadjuvant chemotherapy that consisted of cisplatin and gemcitabine. Because the cancer overexpressed the HER2 protein, I also received trastuzumab, which was very experimental at the time.

To my great relief, the treatment was successful, and I’ve remained cancer-free ever since.

Coping With the Death of a Child

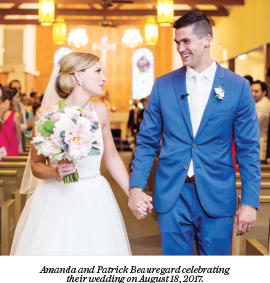

I wish I could say this was the end of cancer’s devastating impact on my life and on my family, but in the fall of 2017, my previously healthy son, Patrick, just 29 years old at the time, was diagnosed with stage 4 colorectal cancer. Complicating the seriousness of the diagnosis was the fact that in addition to the late stage of the cancer, the tumor type was KRAS--positive and microsatellite-stable, further worsening his chance of survival. He died 3 years later on September 6, 2020. (See “Becoming Acquainted With Death,” and “Remembering Patrick H. Beauregard: ‘Selfless in His Efforts to Raise Awareness of Colorectal Cancer in Young Adults,’” both in the October 25, 2020, issue of The ASCO Post.)

As anyone with children knows, the death of a child is a parent’s worst nightmare, and the shock of Patrick’s death remains with me today. I’m not the same person I was prior to Patrick’s diagnosis. His valiant struggle to live, his courage, and his exhaustive attempt to raise awareness of young-onset colorectal cancer and funding for research over the last 3 years of his life are a fitting testament to the amazing person he was. I can say without hesitation or false modesty that he was a better person than I’ll ever be.

Moving Forward

Because of Patrick’s young-onset colorectal cancer diagnosis, my three remaining children are on an earlier colonoscopy screening schedule than the general public. To my relief, their tests have all been negative for any signs of cancer. I’m wondering now whether my young adult daughter should also start mammography screening before the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation that all women get screened every other year starting at age 40.1

Although our family hasn’t undergone genetic counseling and testing, our recent history with cancer has alerted us to the potential that we may be at greater risk for the development of the disease, and we try to stay extra vigilant to reduce that risk.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis and watching loved ones die of the disease leave an indelible mark on your soul. But rather than fall victim to despair, I choose to honor the legacies left by my parents and my son and continue to move forward and live bravely—and positively—like they did.

REFERENCE

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Breast Cancer: Screening. Available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening. Accessed October 28, 2024.

Dr. Beauregard, 68, is Chief Population Health Officer at SoNE Health. He is the author of the forthcoming family memoir Reservation for Nine (Manhattan Book Group Publishers, 2025) and lives in Medfield, Massachusetts.

Editor’s Note: Columns in the Patient’s Corner are based solely on information The ASCO Post received from patients and should be considered anecdotal.