“The function of the formal controlled clinical trial is to separate the relative handful of discoveries that prove to be true advances in therapy from a legion of false leads and unverifiable clinical impressions, and to delineate in a scientific way the extent of and the limitations that attend the effectiveness of drugs.”

—William Thomas Beaver, MD

Over the 4-plus decades following the 1971 National Cancer Act, our clinical trial system has improved the lives of countless cancer patients; however, the process has too often been sluggish and costly, resulting in small, incremental improvements in overall survival. In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report, A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century, which addressed serious concerns that the U.S. clinical trial system is falling far short of its potential to conduct the timely, innovative large-scale trials needed to improve the quality of patient care. Leaders in the oncology community agree that it is time to raise the bar of cancer clinical research by defining clinically meaningful outcomes.

ASCO Takes a Leadership Role

The ability to identify the molecular drivers of carcinogenesis has grown exponentially and, therefore, it is vital to have a trial system nimble and aggressive enough to reap the clinical benefits of that knowledge. In 2012, ASCO President Sandra M. Swain, MD, appointed Lee M. Ellis, MD, as chair of the ASCO Cancer Research Committee. The primary goal of the committee’s efforts during this year was to develop goals for future clinical trials that would produce more clinically meaningful results for our patients. The Committee’s efforts were recently published in a Special Article in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO), “Raising the Bar for Clinical Trials by Defining Clinically Meaningful Outcomes.”1 (See page 120 for more on this important paper.)

Dr. Swain told The ASCO Post, “Far too often, clinical trials result in a statistical endpoint that’s significant but one that doesn’t translate into a meaningful benefit for patients. I fully supported Dr. Ellis, the ASCO Cancer Research Committee, and other members of the working groups, as I felt that it was essential to tackle this issue head on as oncologists and advocates for our patients. We conduct large expensive clinical trials, now we need to emphasize clear clinical benefits for patients. I think the JCO paper is the beginning of an important dialogue to that end.”

The goals and strategies of the ASCO Cancer Research Committee were delineated in the JCO article, in which four disease-specific (pancreatic, breast, lung, and colon cancer) working groups were convened to consider the design of future clinical trials that would produce results that are clinically meaningful to patients.

“Each of the four groups had a chair and co-chair. Along with experts in the four cancers, the groups comprised various stakeholders, including an industry oncologist representative, patient advocates, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-knowledgeable person, and, of course, a statistician. This process began at the initial Committee meeting but evolved into a series of conference calls led by the chairs of each working group,” explained Dr. Ellis, Committee Chair and lead author of the JCO paper.

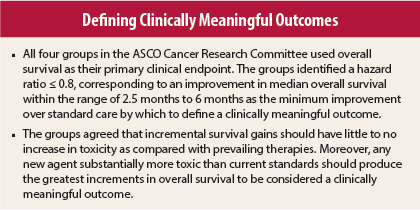

“I pushed for a hazard ratio threshold, recognizing, however, that hazard ratios are dependent on several factors including patient profile and the number of events. Statisticians are reluctant to make hard-and-fast rules when dealing with multiple variables, but I felt it was vital to set a threshold. In the Netherlands, for instance, they’ve been contemplating setting a hazard ratio threshold of 0.07 as a minimum determinate for clinically meaningful outcomes,” said Dr. Ellis, adding, “Europe, for the most part, has employed tougher drug approval standards than the United States.”

Higher Bar for Outcomes

Dr. Ellis commented that pancreatic cancer served as a backdrop for the Committee’s determination to raise the “clinically meaningful” bar. “Once we reached consensus over a higher bar for outcomes, we discussed some recent examples of clinical trials that did not make major advances. The poster child example was erlotinib [Tarceva] in pancreatic cancer, which was presented in a Plenary Session at ASCO’s Annual Meeting in 2005 and published in JCO. However, gemcitabine plus erlotinib didn’t become standard of care, which shows that just because you have a P value doesn’t mean it’s going to be embraced by the oncology community. This illustration, in which an FDA-approved agent conferred an 11-day improvement in overall survival, became the underpinning for the Committee’s work.”

Dr. Ellis noted that the four disease-specific committees worked independently, meeting via regular conference calls to keep everyone in the loop. “There were a lot of strong opinions, and although we didn’t always reach consensus, we did arrive at a reasonable compromise. Since the point of raising the clinical bar is to achieve better outcomes for our patients, I made sure we included patient advocates in all the discussions,” said Dr. Ellis.

After the four committees developed their basic recommendations, they were posted on the ASCO website for feedback from the community. “We read the feedback, which consisted of well over 100 comments, varying in nature from supportive to not shooting high enough or shooting too high. After review, we revised our recommendations based on the consensus of the comments. We presented our revised recommendations to the ASCO Board of Directors and got instructive feedback. This feedback-revision process was repeated several times until the ASCO Board finally accepted it. We then submitted it to JCO, and after peer review, it was published as an ASCO Special Article,” said Dr. Ellis.

Re-envisioning Goals

Dr. Ellis said the Committee recognized that the groups’ descriptions of clinically meaningful outcomes are highly nuanced and affected by numerous factors, which will likely change as standard of care evolves in cancer treatment. He pointed out that although overall survival was selected as the primary endpoint, it did not lessen the value of progression-free survival and other surrogate endpoints in certain clinical scenarios.

“The value of progression-free survival is especially true in disease that produces symptoms related to progression, such as bone metastases, where a significant continuation of progression-free survival could help physicians palliate those symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life,” said Dr. Ellis.

“As pointed out in the IOM’s 2010 report, we need to improve the speed, efficiency, and conduct in our clinical trial network,” he added. “Given the challenge in accruing patients, smaller and smarter trials are needed to lower the costs and turnaround time from concept to completion.”

Asked whether the Committee’s work furthered those goals, Dr. Ellis responded, “Our recommendations do not change the policy of the National Cancer Institute or any other funding organizations, but our work does fit in with the IOM report’s ultimate goals. The days of the 3,000- to 5,000-patient clinical trial evaluating an agent that ultimately leads to marginal improvement is over. Our increasing knowledge of genomics should help us develop smaller and smarter clinical trials that achieve meaningful clinical outcomes. The challenge is in translating what we’ve learned from genomic analyses into a clinical reality.”

Raising the Bar With Innovation

In a JCO editorial, “Time Has Come to Raise the Bar in Oncology Clinical Trials,”2 David M. Dilts, PhD, commented that it is time for oncology trials to become less incremental and more innovative, striving for more, faster. He also stressed that all radical innovations come with risks. For one thing, expectations of patients and regulatory agencies may outstrip the technical capabilities of achieving aspirational trial goals. Thus, it is important to temper expectations with reality.

Another risk is lack of knowledge, noted Dr. Dilts. As acknowledged in the JCO article, validated biomarkers to guide trials are not always available. He suggested that our growing bank of specimens and improved technology to analyze specimens could ameliorate that risk.

Moving forward, Dr. Dilts maintained, every new clinical trial should include “-omics” to help target the right patients and adaptive trial design to help select the treatment arms, thereby reducing total accrual needs. According to Dr. Dilts, several strategies are needed to re-envision and raise the bar for clinical trials. For example, just as there is a need to build a rapid-learning system in oncology, it’s important that such a system is linked to the design of meaningful clinical trials.

Another strategy is learning from institutions that have been set up to drive significant innovations. “The Department of Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), is an organization that focuses on big changes, blending the best of basic and applied research to jump from one innovation curve to another. DARPA makes obsolete current practice and replaces it with something that is an order-of-magnitude better,” Dr. Dilts told The ASCO Post.

“DARPA doesn’t just fund ‘dream teams’; it funds competitions from academia and industry. It focuses on problem-solving regardless of who comes up with the solution. Can you imagine what the state of cancer would be if the government funded that kind of research?” he continued. “Here’s a thought-experiment: A key limiting factor in oncology trials is side effects, so what basic, clinical, and practice teams need to be brought together to achieve the goal of zero side effects regardless of the treatment? That is a DARPA type of goal.”

Important First Step

Dr. Swain noted that the published outcomes of the ASCO Cancer Research Committee represent an important first step that will potentially inspire future investigators to raise the bar in an effort to significantly advance the state of cancer care. Dr. Ellis and his colleagues have laid out an ambitious challenge for clinical investigators, one that will need a concerted effort by government, industry, and patient advocates. An opportunity exists to set the future direction of the entire system, but clinical trialists must be willing to take necessary risks.

“I think that it is past time for some major restructuring of what is considered ‘good research’ in oncology. Raising the bar is an excellent first step, but if we stop there, we are doing a major disservice to oncology patients of 2025,” said Dr. Dilts. ■

Disclosure: For full disclosures of the authors, visit jco.ascopubs.org.

References

1. Ellis LM, Bernstein DS, Voest EE, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology perspective: Raising the bar for clinical trials by defining clinically meaningful outcomes. J Clin Oncol. March 17, 2014 (early release online).

2. Dilts DM: Time has come to raise the bar in oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. March 31, 2014 (early release online).