Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, FASCO

Shilpa Paul, PharmD, BCOP

Fadi G. Haddad, MD

With the currently available BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has transformed from an invariably fatal disorder (10-year overall survival < 10%) to an indolent one, associated with a near-normal life expectancy on optimal tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.1-5 Six BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors are now approved in CML, five in the front-line setting (imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, asciminib), and all six (including ponatinib) are approved as later-line therapies. With this cornucopia of treatment options, what is the optimal front-line therapy for CML that would offer the best treatment value?

Goals of Front-Line Therapy for CML

To address this question, the goals of CML therapy, as defined by CML experts and hoped for by patients, need to be clarified. They have changed over the past 25 years from improving survival as best as possible to normalizing survival and even curing CML.

Today, here are the goals of CML therapy:

(1) Provide a normal life expectancy with as high a quality of life as possible;

(2) Attempt to cure CML molecularly by attaining the highest possible rate of sustained or durable deep molecular response, defined (in our view) as BCR::ABL1 transcripts on the International Scale (IS) < 0.01% for at least 5 years of therapy. This would then translate, if the tyrosine kinase inhibitor is stopped, into a treatment-free remission rate of more than 80%.

(3) Minimize the risks of early and late serious (particularly prohibitive) adverse effects and of mild-moderate chronic adverse effects that affect quality of life;

(4) Make the tyrosine kinase inhibitors available and affordable to 100% of patients.2-4,6

How Do Front-Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Fare in Regard to Treatment Goals?

Any of the five front-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors approved will offer a near-normal survival, provided later-line therapies are implemented promptly among patients who exhibit true CML resistance, simply defined as BCR::ABL1 transcripts (IS) > 1% after 12+ months of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (annual true resistance rate of 1%),7 and those who have serious prohibitive toxicities (eg, recurrent pleural effusions, pulmonary hypertension, pneumonitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, hepatitis, nephritis, enterocolitis, progressive chronic renal failure, neurologic deterioration; annual incidence of 1%–1.5%). The 10-year rates of relative survival (patients age-matched to the general population) and CML-specific survival (accounting for deaths related to CML or its treatment complications) are more than 92%, and they are unlikely to be further improved.1,8

Newer-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, asciminib) have been shown to induce earlier major molecular responses (BCR::ABL1 transcripts [IS] < 0.1%) and deep molecular responses. However, none has been shown so far to increase significantly the rates of durable deep molecular response or treatment-free remission over imatinib therapy.9-12

As far as early and late serious or prohibitive adverse effects, imatinib remains probably the safest tyrosine kinase inhibitor available, with very rare prohibitive or serious adverse effects and rare long-term adverse effects. This is now documented in the largest CML populations treated since 2000. Each of the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors exhibits its own serious, prohibitive and late serious adverse effects, which have also been documented in large CML series, with patients monitored for 10 to 20+ years. Asciminib is the newcomer, and the experience with its efficacy and later toxicities is still limited.

Finally, we come to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor “treatment value,” simply defined as how much are we willing to pay for a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and what benefits do we get in return? As mentioned previously, none of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors is likely to improve survival over imatinib; none has shown so far to improve the overall rates of durable deep molecular response and treatment-free remission; and imatinib appears to be the safest. The latter statement needs to be clarified: In the front-line study comparing asciminib with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the early discontinuation rate (for resistance or adverse events) was 4.5% (with a median follow-up of 16 months), about 3.4% per year—on a par with the discontinuation rate of 2.5% per year with imatinib or other tyrosine kinase inhibitors.9-13 However, the discontinuation rate on the imatinib control arm was 11.1%, about 8.3% annually; the discontinuation rate on second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors was 8.2% to 11.9%, about 6.1% to 8.9% annually.14 These figures are significantly higher than the discontinuation rates of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in historical controlled randomized trials.7,9-11 In our view, this suggests a potential (unconscious?) bias toward discontinuing tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the control arms of this study more than might be truly necessary or indicated.

How Cost of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors May Impact Selection of Front-Line Therapies

With so many articles analyzing the prices of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in CML, what prompted this perspective?2-4,15 It is because dasatinib became available, as of March 2025 in the United States, through the Mark Cuban Cost Plus drug company at a price to the patient of $3,855/year for dasatinib at 50 mg daily and of $6,955/year for dasatinib at 100 mg daily.16

Next, we will review the cost of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the United States in 2025. Because the prices of tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be confusing, even to CML experts and much more so to patients, we will clarify some of the variations in prices that are applicable to most cancer drugs.

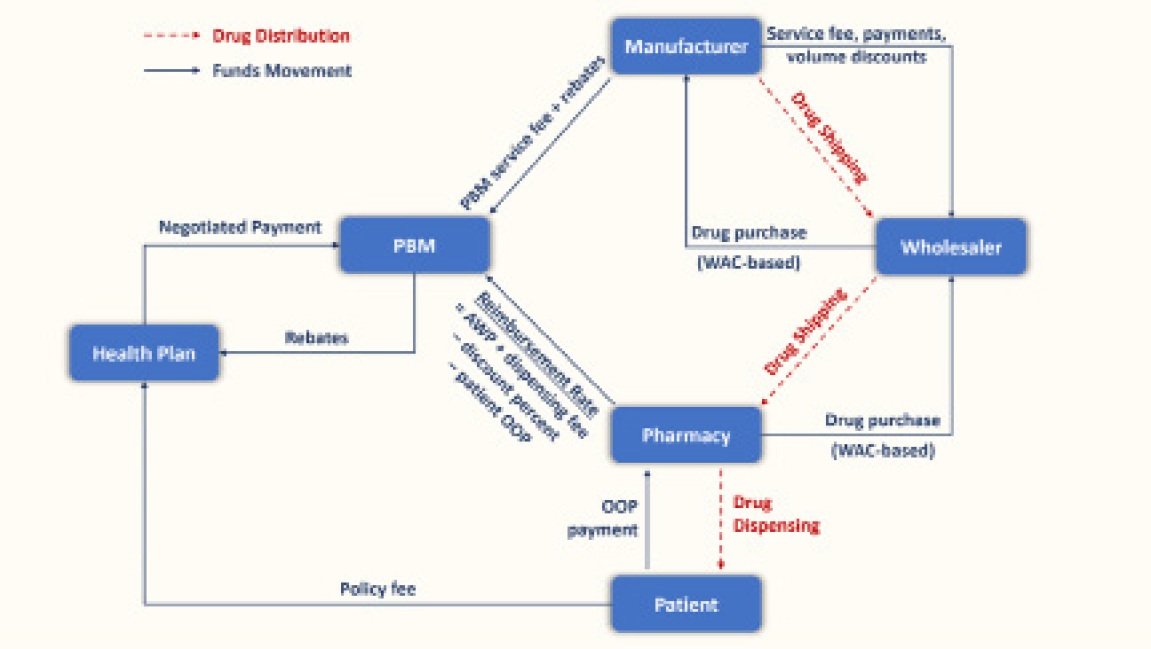

The first question centers on the variations in prices when quoted by drug companies and by pharmacy outlets. Two prices are quoted. The first is the average wholesale acquisition cost (WAC): this is the tyrosine kinase inhibitor price when it leaves the doors of the drug company. The second is the average wholesale price (AWP): this is the price the patient pays for the drug.2,4,15 The latter may or may not be the price paid by the insurers, because of the deals made between the insurers and the drug companies, as well as the in-between interventions of the intermediaries such as the group purchasing organizations and the pharmacy benefit managers. Figure 1 illustrates this complexity, which perplexes the most sophisticated health-care experts, who might even shy away from understanding it.

A brief primer on group purchasing organizations and pharmacy benefit managers is offered here. Pharmacy benefit managers manage prescription drug benefits for about 275 million Americans, acting as intermediaries among pharmacies, drug manufacturers, wholesalers, and insurers. They negotiate rebates from pharmaceutical companies in exchange for favorable placement on insurance formularies, though patients often do not benefit directly from these savings.17-21 Pharmacy benefit managers also profit through “spread pricing,” where they charge insurers more than they pay pharmacies.22 By 2024, the pharmacy benefit managers market was expected to reach nearly $600 billion, with CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx controlling nearly 80% of it.23

Group purchasing organizations, established in 1910, help hospitals to reduce costs by leveraging collective buying power. Their influence grew with the launch of Medicare, Medicaid, and the Medicare Prospective Payment System.24 By 2007, nearly all acute-care and not-for-profit hospitals were group purchasing organization members. Group purchasing organizations fund operations through vendor-paid administrative fees, a practice shielded by a 1986 “Safe Harbor” law exempting them from anti-kickback rules. However, fees often exceed 3% of contract value without strict caps, raising concerns about conflicts of interest.24 Studies in the early 2000s revealed that some group purchasing organization contracts actually raised health-care costs.25,26 Critics argue that the dual roles of group purchasing organizations create anticompetitive risks that warrant greater regulation.24

Let us go back to the two drug prices, the drug company price (WAC) and the patient price (AWP). When the drugs are patented, the AWP is higher than the WAC but not shockingly so. So, the high prices of cancer drugs are blamed fully on drug companies. However, when the drug is a generic, the price spread between the WAC and AWP can be shockingly different, because the for-profit nature of our health-care system has created recent market forces distortions that may not favor patients.4,27-29 Here, the high generic prices are blamed on the intermediaries (group purchasing organizations, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacy outlets, hospitals), who charge additional profits.

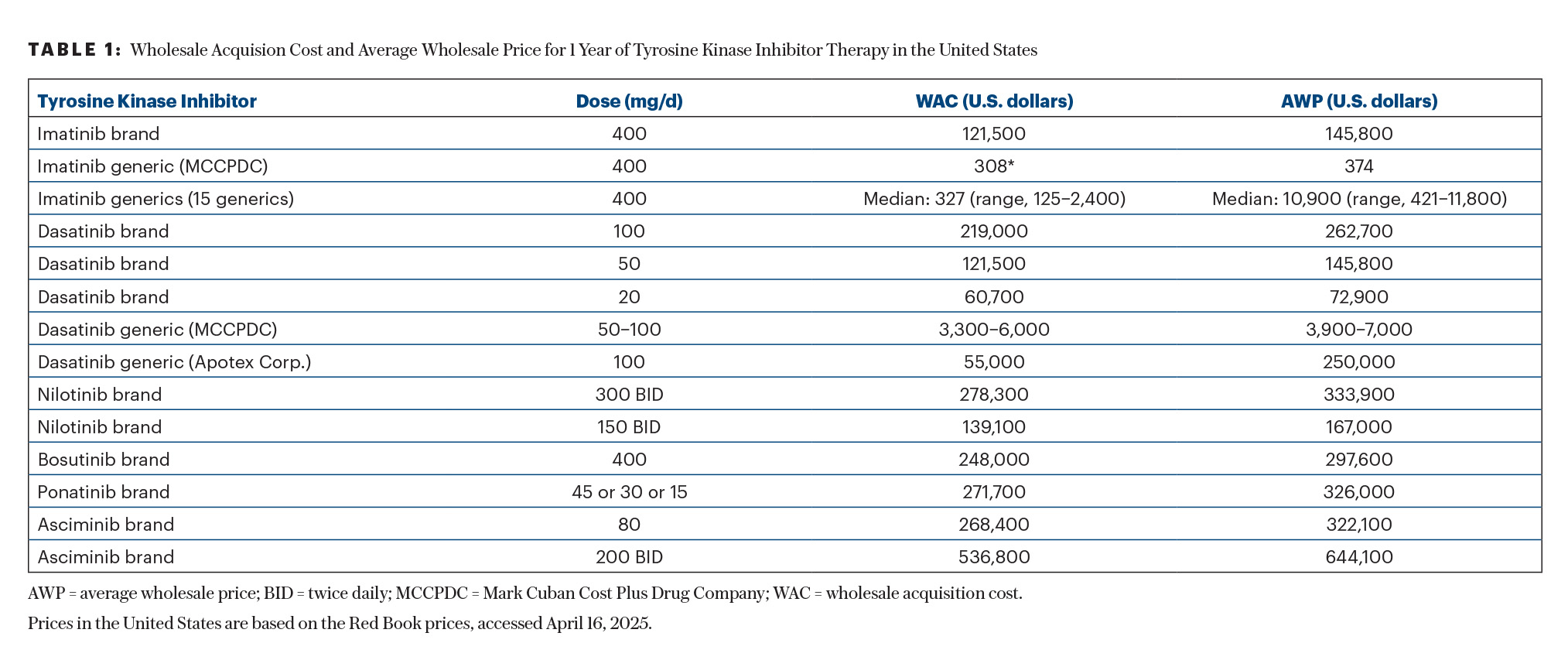

Let us take the example of generic imatinib to clarify the point (Table 1). The patented imatinib (Gleevec) became available in 2001 at a WAC of $26,400/year, a price close to that of interferon (then the competing standard of care).27,30,31 This price increased to $92,000/year by 2012 and to $142,000/year in 2022.6,27,32-35 When the imatinib patent expired in 2015, multiple imatinib generics became available. By historical data, the price of a generic drug should decrease drastically once four to five generics become available. This is what happened to generic imatinib, with the average AWC decreasing to $5,200/year.15

However, the past decade saw the creation of the intermediaries that sustained the high AWP.15,36,37 Despite the availability of more than 15 generics in the United States, the average AWP remained $131,200/year for most imatinib generics.2,38 This was until September 2023, when Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus generic company started offering generic imatinib at cost plus 15%—or at a price to the patient of less than $500/year for imatinib at 400 mg daily.2,4,15 This consequently led to a significant reduction in the prices of imatinib generics—by more than 90%—to an average of approximately $10,000/year—still 20 times higher than the price offered by Cost Plus (Table 1).

In September 2024, generic dasatinib became available in the United States, at a cost of $253,000 per year, due to 180-day exclusivity. In March 2025, Cost Plus started offering dasatinib at 100 mg daily at about $6,955/year and dasatinib at 50 mg daily at about $3,855/year (Table 1). The AWPs of other dasatinib generics and of the patented dasatinib are today more than 60 times the price offered by Cost Plus—for the same drug! This is a real game-changer in cancer care.

Cost Plus and similar generic companies that bypass the drug intermediaries may finally redress the market competition to how it is supposed to function in a capitalistic system, rather than to how it is functioning now, and work better to help patients instead of helping profits at the potential expense of harming patients through financial toxicities or abandonment of care. However, there is one caveat: Cost Plus bills patients directly. This may be an issue with insurers not agreeing to reimburse patients or directing them to buy the drug through their conglomerates’ outlets, which may impose 20% to 25% out-of-pocket cost to the patient reimbursement.

Why Would an Insurer Not Buy the Inexpensive Generic Version?

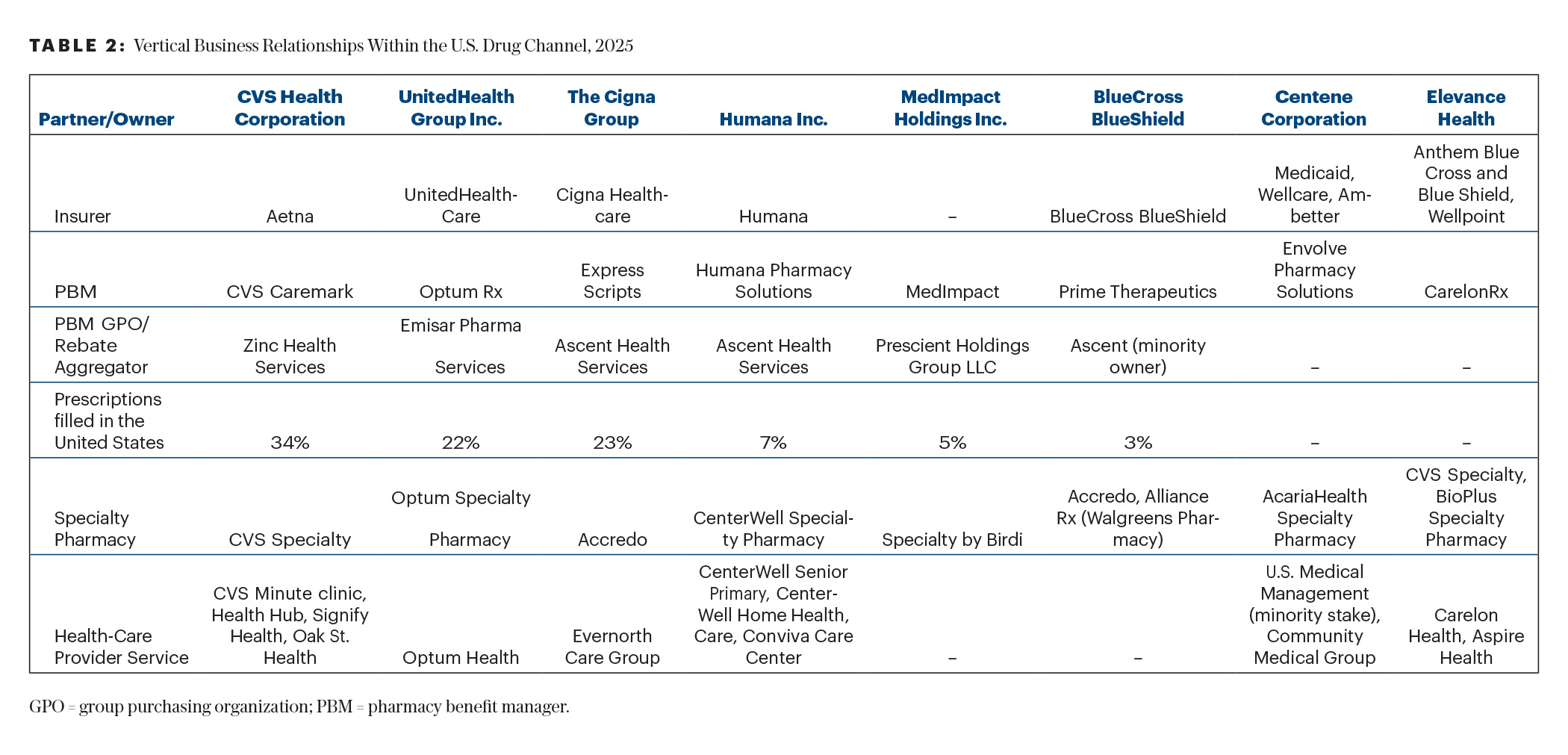

This puzzling question may require a simple primer of the health-care trends that are developing in the past decade. Three of them are important to watch for: (1) the creation and expansion of the group purchasing organizations and pharmacy benefit managers; (2) the consolidation and vertical integration of different health-care entities (that encompass insurers, group purchasing organizations, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacy outlets, hospitals, and physician groups) into large health-care conglomerates (some are illustrated in Table 2); and (3) the increasing out-of-pocket expenses imposed on patients by their insurers (20%–25% today).4 The increasing out-of-pocket expenses were based on the concept of “consumerism”: if patients have “skin in the game,” they would be more prudent consumers. But this could, of course, result in treatment abandonment.39

Why may insurers not want to buy the Cost Plus imatinib (< $500/year) or dasatinib (50 mg/day = $3,855/year) generic drugs and instead buy generics that it pays much more for (and the patient would also pay 20%–25% out-of-pocket expenses = $26,000/year; Table 1). The Affordable Care Act, in particular the Medical Loss Ratio provision, requires that insurers spend 80% to 85% of their premium revenues on patient care.40 Instead of paying outside entities, they started forming larger health-care conglomerates, which include the other entities that provide health care (Table 2).

The purported aim of such vertical integrations and of the health-care conglomerates is to provide continuous care within the same structure and optimize care while reducing cost and waste. At the same time, the 85% mandated patient care would flow in a “closed-loop” system, where 100% of the revenues remain within the conglomerates. In addition, the patients’ out-of-pocket expenses increase the profits for the conglomerated entity through treatment abandonment as well as revenue generation. This complex health-care system is becoming more difficult to comprehend by health-care providers and patients.

What Then Is the Optimal Front-Line Therapy for CML Today?

With the availability and awareness of the existence of generics of imatinib and of dasatinib at low AWP (through Cost Plus and similar generic companies), 100% of patients with CML today should be able to attain all four goals of CML therapy: near-normal survival; high rates of durable deep molecular response and treatment-free remission; low rates of severe and prohibitive adverse effects; and access and affordability to all, the fortunate and the less fortunate.

What then is the optimal front-line CML therapy today? This question may produce different answers depending on which CML expert is asked; therefore, we offer our personal view. When survival and safety are the goals of therapy, generic imatinib at less than $500/year (less than the price of a cup of coffee daily) offers the best treatment value. If earlier achievement of durable deep molecular response or treatment-free remission is the goal, and in patients with higher-risk CML, generic dasatinib at 50 mg through Cost Plus or similar generic companies may offer the best treatment value. The other generic and patented tyrosine kinase inhibitors have to offer such lower prices to be considered as front-line therapies. For later-line therapies necessitated by prohibitive toxicities, true CML resistance, or intolerance to both imatinib and dasatinib, we hope other generic tyrosine kinase inhibitors will become available at reasonable prices and good treatment values, which should not exceed $15,000 to $20,000/year.

Conclusion

The availability of generic imatinib and of generic dasatinib, through Cost Plus and similar generic companies that bypass the intermediaries (pharmacy benefit managers, group purchasing organizations, and pharmacy outlets), now offers the best treatment value for front-line CML therapy. One issue that remains to be resolved is whether Cost Plus can charge the insurers directly or the patients can be reimbursed by the insurers for the amounts they pay to Cost Plus. This appears to be a nonissue, were it not for the “vertical integration” of the different health-care entities into conglomerates.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Kantarjian has received honoraria and served as a consultant or advisor to AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage Pharma, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, KAHR Medical, Novartis, Pfizer, Shenzhen TargetRx, Stemline Therapeutics, and Takeda; and has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage Pharma, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, ImmunoGen, and Novartis. Dr. Paul reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Haddad has received consulting fees from Amgen.

REFERENCES

- Kantarjian H, Jabbour E, Cortes J: Chronic myeloid leukemia, in Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al (eds): Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st ed. New York, NY; McGraw Hill Education; 2022.

- Haddad FG, Kantarjian H: Navigating the management of chronic phase CML in the era of generic BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 22:e237116, 2024.

- Senapati J, Sasaki K, Issa GC, et al: Management of chronic myeloid leukemia in 2023: Common ground and common sense. Blood Cancer J 13:58, 2023.

- Kantarjian HM, Begna K, Jabbour EJ, et al: Optimal frontline therapy of chronic myeloid leukemia today, and related musings. Am J Hematol 99:1855-1861, 2024.

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian H: Chronic myeloid leukemia: A review. JAMA 333:1618-1629, 2025.

- Kantarjian HM, Welch MA, Jabbour E: Revisiting six established practices in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Lancet Haematol 10:e860-e864, 2023.

- Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saubele S, et al: Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-Year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia 31:2398-2406, 2017.

- Sasaki K, Strom SS, O’Brien S, et al: Relative survival in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia in the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor era: Analysis of patient data from six prospective clinical trials. Lancet Haematol 2:e186-e193, 2015.

- Kantarjian HM, Hughes TP, Larson RA, et al: Long-term outcomes with frontline nilotinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: ENESTnd 10-year analysis. Leukemia 35:440-453, 2021.

- Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al: Final 5-year study results of DASISION: The Dasatinb Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients trial. J Clin Oncol 34:2333-2340, 2016.

- Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, et al: Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: Final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia 36:1825-1833, 2022.

- Hochhaus A, Wang J, Kim DW, et al: Asciminib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 391:885-898, 2024.

- Guilhot F, Hehlmann R: Long-term outcomes of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 145:910-920, 2025.

- Cortes JE, Hochhaus A, Hughes TP, et al: Asciminib demonstrates favorable safety and tolerability compared with each investigator-selected tyrosine kinase inhibitor in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase in the pivotal phase 3 ASC4FIRST study. 2024 ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition. Abstract 475. Presented December 8, 2024.

- Kantarjian H, Paul S, Thakkar J, et al: The influence of drug prices, new availability of inexpensive generic imatinib, new approvals, and post-marketing research on the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in the USA. Lancet Haematol 9:e854-e861, 2022.

- Price of generic dasatinib through the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company. Available at https://www.costplusdrugs.com/medications/dasatinib-50-mg-tablet-60/. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Mattingly 2nd TJ, Hyman DA, Bai G: Pharmacy benefit managers: History, business practices, economics, and policy. JAMA Health Forum 4:e233804, 2023.

- Federal Trade Commission: Pharmacy benefit managers: The powerful middlemen inflating drug costs and squeezing main street pharmacies. July 2024. Available at https://www.ftc.gov/reports/pharmacy-benefit-managers-report. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- McNulty R: 5 Things to know about PBMs’ influence on drug costs and access. Available at https://www.ajmc.com/view/5-things-to-know-about-pbms-influence-on-drug-costs-and-access. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Feldman BS: Big pharmacies are dismantling the industry that keeps US drug costs even sort-of under control Available at https://qz.com/636823/big-pharmacies-are-dismantling-the-industry-that-keeps-us-drug-costs-even-sort-of-under-control. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Pharmacy benefit management. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmacy_benefit_management#cite_note-2. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Cohen JP: Lawmakers want to break up healthcare conglomerates, forcing them to shed pharmacies. December 16, 2024. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuacohen/2024/12/16/lawmakers-want-to-break-up-healthcare-conglomerates-force-shedding-of-pharmacies/. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Mikulic M: Pharmacy benefit managers: Statistics & facts. February 28, 2024. Available at https://www.statista.com/topics/11037/pharmacy-benefit-managers/. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Group purchasing organization. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_purchasing_organization. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Schulman KA: Understanding the history of group purchasing organizations and pharmacy benefit managers. Available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/understanding-history-group-purchasing-organizations-and-pharmacy-benefit-managers. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Scanlon WJ: Group purchasing organizations: Pilot study suggests large buying groups do not always offer hospitals lower prices. April 30, 2002. Available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-02-690t.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Experts in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: From the perspective of a large group of CML experts. Blood 121:4439-4442, 2013.

- Wainer D, Sindreu J: The world swallows U.S. pills. Available at https://www.magzter.com/stories/newspaper/The-Wall-Street-Journal/THE-WORLD-SWALLOWS-US-PILLS?srsltid=AfmBOoo035FREib2AvOGZvgZyzIhk6UXoufJUkFvgHvc-G4wNF4VJNom. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Robbins R, Abelson R: The opaque industry secretly inflating prices for prescription drugs. The New York Times, June 21, 2024. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/21/business/prescription-drug-costs-pbm.html. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Light DW, Lexchin JR: Pharmaceutical research and development: What do we get for all that money? BMJ 345:e4348, 2012.

- Vasella D, Slater R: Magic Cancer Bullet: How a Tiny Orange Pill Is Rewriting Medical History. New York; Harper Collins Publishers; 2003.

- Kantarjian H: Why drugs cost too much and how prices can be brought down. Cancer Letter 39:7-11, 2013.

- Kantarjian H, Rajkumar SV: Why are cancer drugs so expensive in the United States, and what are the solutions? Mayo Clin Proc 90:500-504, 2015.

- Kantarjian H, Steensma D, Rius Sanjuan J, et al: High cancer drug prices in the United States: Reasons and proposed solutions. J Oncol Pract 10:e208-e211, 2014.

- Kantarjian H, Light DW, Ho V: The ‘American (cancer) patients first’ plan to reduce drug prices: A critical assessment. Am J Hematol 93:1444-1450, 2018.

- Jones GH, Carrier MA, Silver RT, et al: Strategies that delay or prevent the timely availability of affordable generic drugs in the United States. Blood 127:1398-1402, 2016.

- Kantarjian H, Patel Y: High cancer drug prices 4 years later: Progress and prospects. Cancer 123:1292-1297, 2017.

- Jenei K, Lythgoe MP, Prasad V: CostPlus and implications for generic imatinib. Lancet Reg Health Am 13:100317, 2022.

- Potter W: I was a health insurance executive. What I saw made me quit. The New York Times, December 18, 2024. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/18/opinion/health-insurance-united-ceo-shooting.html. Accessed May 14, 2025.

- Provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provisions_of_the_Affordable_Care_Act#cite_note-38. Accessed May 14, 2025.

Dr. Kantarjian is Professor and Chair of the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Paul is Senior Manager of the Hematology Oncology Clinical Program at Longitude Health. Dr. Haddad is Assistant Professor in the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.