In this installment of The ASCO Post’s Living a Full Life series, guest editor Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, spoke with neurosurgeon Alfredo Quiñones-Hinojosa, MD, FAANS, FACS, the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Dean of Research, Monica Flynn Jacoby Chair of Neurologic Surgery, and William J. and Charles H. Mayo Professor IV, at Mayo Clinic’s campus in Jacksonville, Florida.

ALFREDO QUIÑONES-HINOJOSA, MD, FAANS, FACS

On the value of family: “Even though we were poor, the most important thing we had was family. It was a great support system, and it gave me many of the tools necessary for my life and career.”

On entering the field of neurosurgery: “My decision wasn’t without its trials and tribulations. I feel pain every time I lose a patient, but my pain is nothing compared to the pain that family feels. Every single patient takes a little bit of my heart.”

On keeping things in perspective: “It is important to be successful because success will give you confidence. But it is also important to welcome failure because failure will allow you to build character. When you put both together, it allows you to build wisdom.”

Early Years

The first born of six children, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa grew up in a small farming town on the outskirts of Mexicali in Mexico, directly across the border from Calexico, California. His motivation to succeed blossomed early; at the age 5, he peddled homemade snacks to drivers at local gas stations to earn extra money for the family.

His eventual move to the United States was inspired by his uncles, who were part of the Bracero program, which allowed farmers in the western United States to recruit and employ “otherwise inadmissible aliens” from Mexico to work on farms and railroads. “My uncles would cross the border to the United States, and for 6 months, they would do hard farm labor. When they returned home to Mexico, they would bring us food and small gifts. But even through the eyes of a small boy, I saw the inequity among people and how the rich got richer as the poor got poorer,” he explained.

A Nurturing Family

“During my early years, our family of eight lived in a small, two-bedroom house behind a gas station where I used to pump gas to help our family,” Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa continued. “I used to go out in irrigation canals and catch crayfish and shrimp. I remember standing on the roof of our house, looking at the stars, and thinking I wanted to be an explorer. But even though we were poor, the most important thing we had was family. It was a great support system, and it gave me many of the tools necessary for my life and career.”

Education was also important, and Dr. Quiñones--Hinojosa thrived at the local public school. He eventually graduated with a teaching license from a community college at the age of 18. But he was also restless and full of ambition, dreaming of a different future. In his early teens, he was hopping the border fence and spending summers traveling in the back of a tarp-covered pickup truck to the San Joaquin Valley in California to pick tomatoes and prepare cotton fields for harvest and bring in extra money for his family.

“But on January 2, 1987, I was born again, because that’s the day I decided I was going to hop the fence one last time into the United States and find permanent work. At first, I thought I would work for a couple of years and then go back. And those 3 years have become more than 3 decades now,” said Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa.

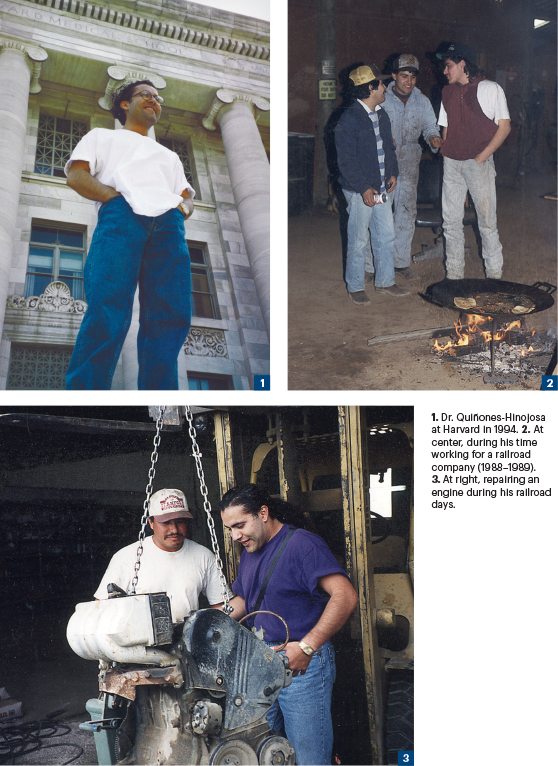

As a farm worker, he quickly mastered machines and instruments. “In Fresno, California, I was able to drive a sophisticated moving tomato picker with all kinds of sharp blades and a crew of eight people on top of it working and picking the right tomatoes,” he shared. A quick and ambitious learner, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa was soon leveling land and digging ditches, moving irrigation pipes twice a day in mud up to his knees. He eventually became a foreman for a railroad company in the port of Stockton, California, where he welded, painted, and maintained tanks filled with sulfur and/or liquified petroleum gas (LPG).

One day, while working with the railroad company, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa was repairing a safety valve for an LPG railroad tanker, lost a piece of equipment in the tank, and fell into the deep tank. Unable to avoid breathing in dangerous LPG fumes, he lost consciousness and nearly died while his brother-in-law, Ramon, risked his own life to go to the bottom of the tank to pull him out. Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa was rushed to the hospital, where he regained consciousness and eventually recovered. However, that life-threatening mishap caused a shift in the 21-year-old’s thinking. “That near-death experience taught me that I wanted to care for other human beings. And to do that, I realized I would need to resume my education,” he related.His memoir, Becoming Dr. Q (originally published by UC Press and most recently rereleased by Mayo Clinic Press) recounts these moments and trajectory in great detail.

Ambition and Drive Defeat Overwhelming Odds

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa continued to work for the railroad company, studying English at night at the the local San Joaquin Delta Community College. He also tutored Spanish-speaking students in math and science and joined the debate team with an eye toward improving his public speaking skills and command of English. After earning a scholarship to the University of California at Berkeley to study psychology, he found an intriguing mentor, Joe Martinez, PhD, who ran a neurobiology lab.

“Even when I was still struggling with English, I always excelled at calculus and chemistry, so being introduced to a neurobiology lab accelerated my passion for the sciences. Dr. Martinez was a terrific mentor, bringing a degree of excitement into his work that was contagious,” he commented.

According to Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa, his lab experience early on was primarily centered on washing petri dishes and pipettes, not doing experiments. “I was the best petri dish washer in the world. I loved it. I was fast, efficient, and organized, and, of course, the postdocs and everybody else saw my enthusiasm and work ethic. We tend to underestimate the power of doing everything with passion, but people pay attention. So, I’m interviewed by all the labs, and guess who takes me into his lab? My former mentor, Joe Martinez. And that’s when he told me I was no longer a dishwasher.”

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa continued: “Dr. Martinez said we’re now studying long-term potentiation in the nucleus accumbens, a part of the brain that is important for pleasure, and he wanted me to test the hypothesis that the connection between two parts of the brain—in this case the lateral entorhinal cortex in the hippocampus and the nucleus accumbens—is monosynaptic, and the hypothesis that it is dependent on an opioid receptor. Of course, at the time, all this stuff went over my head, and I had no idea what was going on. But I went into the library and started really digging.”

By the end of that year, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa was accepted into the Harvard Medical School MD program and subsequently into the PhD program during his second year of medical school. “I discovered the connection between those two areas of the brain and wrote my first paper. That success is due, in part, to the invaluable role of my mentor. It’s one person seeing you washing petri dishes and believing in you. Sometimes, that’s all it takes,” he said.

A Serendipitous Brain Operation Leads to a Decision

Asked about his decision to pursue neurosurgery, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa stated: “One night, toward the end of my third year at Harvard Medical School, I was walking between what’s called The Pike, the long corridor that connects the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Peter Bent Hospital. I pass this guy who pulls me over and introduces himself. I knew he was Dr. Peter Black because he was on the cover of the Harvard Magazine. He asked where I was going, and I said to the Countway Medical Libraryto study. Out of the blue, he asks if I’d like to see a brain surgery.”

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa continued: “With that, he walks me into the locker room, gives me a set of scrubs and walks me to the OR—for the first time in my life in an operating room. I see a whole group of people and the face of a patient who is talking to a psychologist. I go to the other side of the table and see the brain open. I literally felt my knees buckle because I didn’t know how to react to such an amazing sight and the fact that a human being was able to trust another human being to touch his brain, to have it open, and to be awake, talking, and doing tasks.

That single experience planted the neurosurgery seed in the mind of Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa. “It took me another year to convince myself (and everyone else) that not all neurosurgeons were arrogant. Then my friends started getting behind me, and, of course, my wife, Anna, also supported my decision to pursue neurosurgery.”

He continued: “My decision wasn’t without its trials and tribulations. Now that I look back, if you were to ask me my advice for our young generation entering the field, it’s simple: I feel pain every time I lose a patient, but my pain is nothing compared to the pain that family feels. But as a surgeon, it is vitally important to remember you are not alone on this difficult but rewarding journey. Every single patient takes a little bit of my heart, and it accumulates. It’s not like you recover from that.”

Guest Editor

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

Dr. Abraham is Chairman of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Cleveland Clinic and Professor of Medicine at Lerner College of Medicine.

About a year and a half ago, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa started seeing a therapist to talk about these feelings. “I think this is probably the reason many brain surgeons are viewed as arrogant; they used that as a defense mechanism. I am beginning to reflect upon that aspect of my career. I really do believe that even in my own specialty, I now have colleagues asking me, should we begin to talk about our complications, our morbidities, our mortality openly, not just the technical aspect but the emotional toll that it takes?”

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa thrived in medical school, immersing himself in research, receiving fellowships and other academic honors, and graduating cum laude. He also became a U.S. citizen and gave the commencement speech at his Harvard Medical School graduation (class of 1999). From Harvard, he moved back to California, where he completed an internship in general surgery, a postdoctoral fellowship in developmental and stem cell biology, and a residency in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). He currently holds three distinguished positions: the William J. and Charles H. Mayo Professor and Chair of Neurologic Surgery, the Monica Flynn Jacoby Endowed Chair,and the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Dean of Research at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida.

Mentoring and Innovative Research

According to Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa, one of the most rewarding parts of his career is teaching and mentoring. “I meet with my residents every other Monday at 12:00 to 1:00 PM over lunch and talk about different topics, including movies, literature, clinical care, and family, with an emphasis on science, technology, and innovation, because I realized I cannot defeat this foe with my hands in the operating room alone. We have to gain more scientific knowledge. And that’s what the laboratory means: you fail over and over and over. And when the experiment doesn’t work, you must look at it in a different way. The next experiment doesn’t work, and suddenly something works, and you catch onto that, and it becomes a little part of a paper. And then you begin to put it in a story.”

For Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa, storytelling is amazingly important to neurosurgery. “I encourage our youth to keep doing it. And don’t be afraid of missing shots. We miss so many things in life, so many shots. I have failed more times than I have succeeded in my life, but I keep going because in failure there is much learning as well,” he said.

He continued: “I am a surgeon, first and foremost, and as a physician, I am someone who gives hope through the work I do. Our work right now is focused on the premise that we go into the operating room and do these amazing surgeries and take these tumors out of patients. But instead of letting them go to pathology and/or biomedical waste, I’m asking my patients for permission to take that tissue to the laboratory to see whether we can find cures for brain cancer, and therefore make them part of history. I realized I had a unique opportunity to make my patients part of history, to make them feel they have hope, to make them feel their disease does matter.”

In 2004 and 2005, when he was at UCSF, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa began to work in the laboratory with glioma stem cells. “That sort of migrated toward understanding not only the heterogeneity that exists in brain cancer, but also how to implement new therapies. That led me to understand we can use fat (adipose tissue) as a Trojan Horse; we can engineer it with biodegradable nanoparticles. From that came new discoveries, new patents, new ways to treat the disease. And now we are in the process of opening our first investigation of a new drug with the use of stem cells from fat and moving forward, also engineering them, and treating pet dogs that develop spontaneous tumors. I even moved more and more away from using induced animal models to using spontaneous animal models, to using “brains-on-a-chip” that we design in our laboratory to mimic brain cancers from humans. The idea is to create an avatar for each patient where we can test therapies. That has led to a multitude of discoveries, papers, books, and even companies I’ve started. So, we have a long way to go in brain cancer, but the future is very bright.”

Professional Accomplishments

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa leads a National Institutes of Health–funded research laboratory to cure brain cancer. His research focuses on brain tumors and stem cell migration, health-care disparities for minorities, and clinical outcomes for neurosurgical patients. Currently, he has 11 submitted patents and started a new company named Dome Therapeutics, LLC.

Given his prominence in the field, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa is frequently invited to give presentations on his research to both national and international audiences, and he has authored numerous journal articles, book chapters, and abstracts. Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa is Editor-in-Chief of one of the most widely read operative neurosurgical textbooks: Schmidek & SweetOperative Neurosurgical Techniques (6th and 7th editions, Elsevier). Furthermore, he is one of the authors of Controversies in Neuro--Oncology (1st edition, Thieme), which was awarded first prize by the British Medical Association.

In 2011, Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa cofounded Mission: BRAIN (Bridging Resources and Advancing International Neurosurgery, www.missionbrain.org). This nonprofit foundation provides neurosurgical expertise and resources to patients, caregivers, and health-care providers in underserved areas around the world. Teams have made trips to Mexico, the Philippines, Peru, and Haiti to mention a few. The foundation has over 1,000 active medical/surgical members around 80 chapters in over 23 countries and its current goal is to take volunteers to the public hospital in remote areas of the world, to perform surgeries on patients who cannot afford to travel to any of the major tertiary care centers in the United States.

Sharing Lessons Learned

Asked for a closing thought, Dr. Quiñones--Hinojosa commented: “I would say it is important to keep things in perspective. It is important to be successful because success will give you confidence. But it is also important to welcome failure because failure will allow you to build character. And when you put both together, it allows you to build wisdom. That’s something we tend to forget in our society; it’s the yin and yang that bring harmony to life and society.”

Dr. Quiñones-Hinojosa also shared his thoughts on the importance of finding one’s passion. “Find what you’re good at. And for me, I was telling my students, you know what I’m good at, surrounding myself with people who are brighter than me. If you’re passionate about your work, you will never be dissatisfied. Passion drives success, and success leads to further enriching experiences. But in the end, the most important thing is to remember why we became doctors in the first place: to serve our patients. I never forget that.”