In January 2021, two of us wrote in these pages about our field’s pressing need to pivot away from identifying and deploying the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) when it comes to targeted oncology therapies.1 We argued that, instead, one should be looking for the “optimal dose”—the dose that best balances efficacy and toxicity. We used the newly described KRAS G12C inhibitor sotorasib as a contemporary example of the MTD issue. The phase I trial of this drug was designed to find a dose that was toxic in 25% to 30% of subjects, even though responses were seen at lower doses. The area under the curve of the drug at administered doses of 960 mg and 240 mg was identical, and administering more than 240 mg orally did not yield more drug entering the bloodstream. The extra drug simply passes through the gastrointestinal tract, producing side effects that are likely unnecessary. We urged the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to require the sponsor to test the drug at lower doses.

Garth Strohbehn, MD, MPhil

Allen Lichter, MD

Mark Ratain, MD

The FDA granted accelerated approval to sotorasib for the treatment of KRAS G12C–mutant non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at a dose of 960 mg in May 2021 but also required several postmarketing trials, including a dose-ranging trial comparing 960 mg vs 240 mg and a phase III confirmatory trial comparing sotorasib with docetaxel. Furthermore, the FDA announced Project Optimus, a regulatory framework that would require all new oncology drugs to undergo a formal dose-response study to select the optimal dose for their registration trial. The era of seeking out the MTD and taking that dose forward is now over.

What has happened to sotorasib over the past 3 years? Are we closer to understanding the optimal dose of this agent? Let’s review the data.

Dose-Ranging Study

The FDA-mandated dose-ranging study, which compared 960 mg with 240 mg and enrolled 209 participants, was completed in 2022,2 and results were presented in the fall of 2023.3 Although there was the suggestion of a trend toward a better outcome at 960 mg, there was no statistically significant improvement in any efficacy metric. The median overall survival was not statistically different at 13.0 months for 960 mg and 11.7 months for 240 mg. Progression-free survival, the primary endpoint in the phase III trial, was identical in the two arms.

As anticipated, the incidence of grade 3 treatment-related adverse events at the higher dose was greatly increased (35.6% vs 19.2%), often resulting in dose reduction or treatment interruption (39.4% vs 22.1%). Despite this incremental toxicity without benefit, the sponsor and the principal investigator for this study claimed this study establishes the superiority of the higher dose.3 But when one looks at the data objectively, it is impossible to conclude that 960 mg is the better option.

Phase III Confirmatory Trial

The phase III study had its own well-documented problems.4 The trial randomly allocated 345 participants with advanced NSCLC who had disease progression on platinum chemotherapy plus a checkpoint inhibitor to receive either sotorasib at 960 mg or docetaxel. The median progression-free survival was 5.6 months vs 4.5 months, favoring the sotorasib arm, with a hazard ratio of 0.66. Case closed? Sotorasib is superior to docetaxel in this population?

Not so fast. During its review, the FDA noted there was asymmetric early dropout among participants in the study, with greater dropout seen among those in the docetaxel arm, raising concerns that investigators’ assessments of progressive disease had biased the study in favor of the sotorasib arm, perhaps to enable crossover from docetaxel to sotorasib prior to blinded, central assessment of disease progression. To review the trial results and decide the next regulatory steps, the FDA convened the Oncology Drug Advisory Committee (ODAC), an independent third party comprising oncologists, statisticians, and patient advocates. After hearing nearly 8 hours of sponsor and FDA arguments, ODAC ultimately concluded, in a vote of 10 to 2, that these conduct issues had irreparably biased the study results, rendering it “uninterpretable.”5

Subsequent Phase III Trial

A third recently published study tested sotorasib in 160 participants with metastatic colon cancer with the KRAS G12C mutation.6 Here, the agent was used in combination with panitumumab, an EGFR inhibitor. Two dose levels of sotorasib, 960 and 240 mg, were used. The control arm was physician’s choice of trifluridine/tipiracil or regorafenib. Both the 960- and 240-mg sotorasib arms were statistically superior to the control arm, with hazard ratios for progression-free survival of 0.49 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.30–0.80) and 0.58 (95% CI = 0.36–0.93), respectively. Given the overlapping confidence intervals and modest difference in hazard ratio, one cannot conclude that the higher dose had better efficacy.

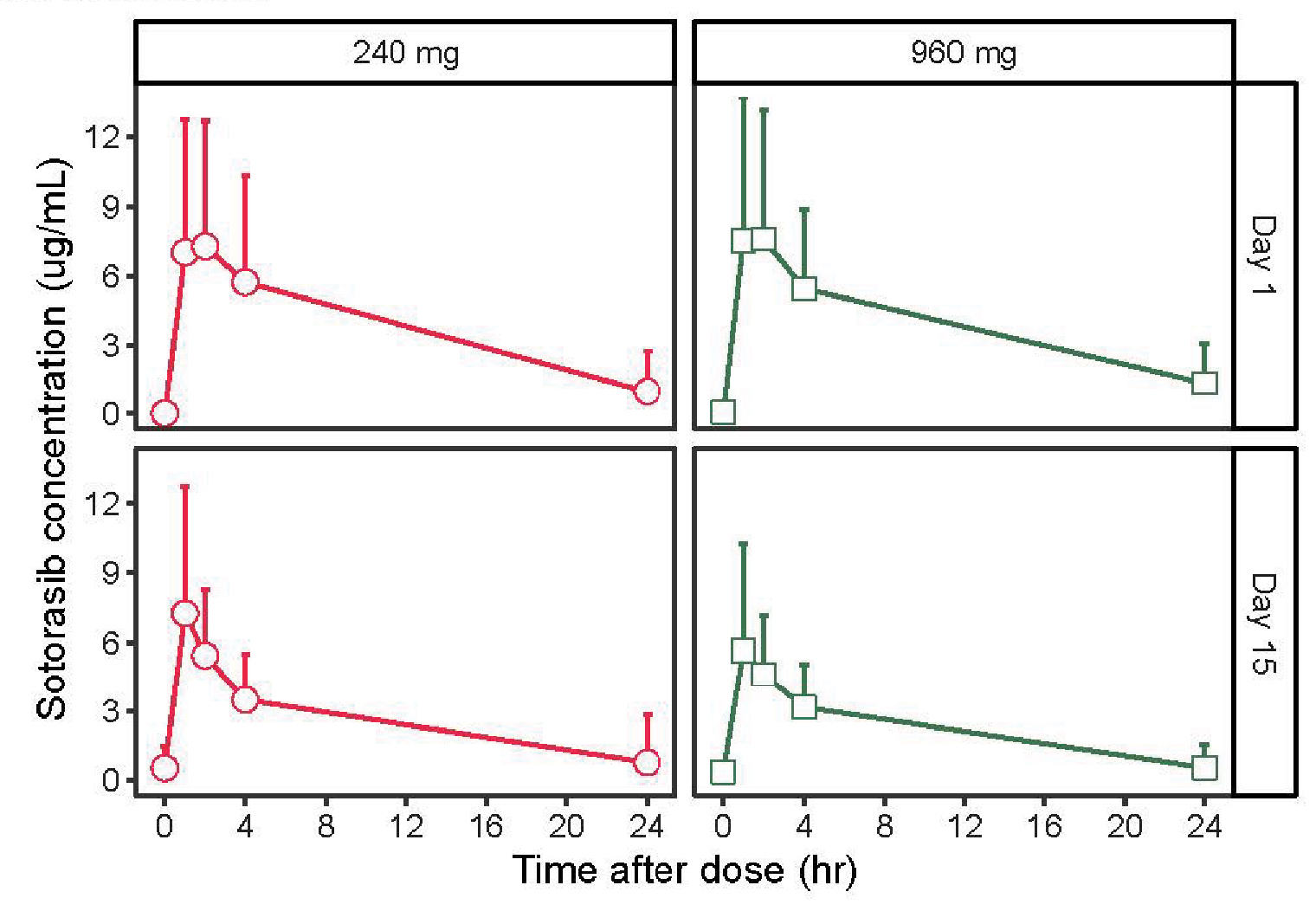

The study also included measurements of serum concentration of sotorasib as a function of the two dose levels on day 1 and day 15 of the study. As the authors noted, “The pharmacokinetic properties of sotorasib and panitumumab were consistent with those seen in prior studies, and similar exposures were observed with the two dose levels of sotorasib [Figure 1].” In fact, a visual inspection of the curves finds them to be not just “similar” but indistinguishable!

FIGURE 1: Pharmacokinetic concentration-time profiles following oral administration of sotorasib at 960 mg or 240 mg and intravenous infusion of panitumumab at 6 mg/kg. Reprinted with permission of Fakih MG, et al.6

The editorial that accompanied this publication comments on the “appropriate dose” and states that the higher dose of 960 mg is needed, based primarily on the nonsignificant (and clinically dubious) “advantage” in progression-free survival at 960 mg. Yet the trial’s protocol did not prespecify a comparison between the 240-mg and 960-mg sotorasib arms.7 Moreover, the pharmacokinetic data indicate the absorption process for sotorasib is saturable. Administering higher doses does not increase the plasma concentrations and thus cannot provide any greater efficacy than the lower dose. On the other hand, the 960-mg dose increases the revenue the sponsor can generate. More on this later.

The FDA’s Task

Where does this leave the FDA? First, in KRAS G12C–mutated NSCLC, a confirmatory trial needs to be repeated, as the initial study was irrevocably flawed. Sotorasib is clearly an active agent in this disease, but is it better than docetaxel head-to-head? One drug costs about $21,000 per month, whereas the other costs about $600 per month. We need to know whether one is an improvement over the other. Possibly, the next study should enroll participants who have had disease progression on docetaxel and compare sotorasib with physician’s choice in the third-line setting. The drug may have a role as a single agent in this setting, given its clear activity.

Second, if the sponsor wants to continue marketing this drug, it should be required to revise the package insert to a dose of 240 mg daily. We note the FDA should have the authority to rescind the accelerated approval given the sponsor did not successfully conduct a randomized trial to “verify and describe the clinical benefit of sotorasib.”8 Furthermore, the required postmarketing study of 960 mg vs 240 mg supports the 2021 FDA assessment that a dose of 960 mg is inappropriate, and a label revision would be a better option than drug withdrawal.

Third, all clinical trials should limit the dose of sotorasib to 240 mg or less. The sponsor is free to test the hypothesis that a higher exposure is superior, but those studies should evaluate 120 to 240 mg twice daily vs 240 mg daily, given the aforementioned absorption issues.

The Prescriber’s Dilemma

Lastly, what should prescribers do? The 960-mg dose is recommended by the sponsor in the FDA-approved label for the drug. Although it is not medically negligent to prescribe that dose, it is the wrong clinical decision, since the additional 720 mg daily adds to the toxicity and cost patients experience without making them any better off. Sotorasib’s list price is just over $21,000/mo. It is available as 120-mg or 320-mg tablets, and thus patients would take three or eight tablets a day with the 960-mg dose. Given that a dose of 240 mg is sufficient, a single 1-month prescription of 120-mg tablets can last 4 months.

Such a change would take a substantial bite out of the revenue sotorasib could generate, giving the sponsor tens or hundreds of millions of reasons to maintain the status quo of the higher dose. Since the studies the sponsor has performed to date do not provide clear evidence that the higher dose is needed, the sponsor is left to cherry-pick pieces of evidence that support its claim, bury the pharmacokinetic data deep in supplements to its papers, and use press releases and websites devoid of context to tout the higher dose.

But in the end, we believe oncologists, as a community that strives to use the scientific method to improve patient well-being, should hold fast and look at the primary data. We also encourage the FDA to act as soon as feasible to protect patients with KRAS-mutated cancers from receiving an unnecessarily toxic dose of an important drug.

Authors’ Addendum: While this article was in press, sotorasib’s sponsor issued a press release9 reporting that the FDA had provided it with a complete response letter, in which the FDA (1) rejected the supplemental new drug approval for sotorasib in second-line treatment of NSCLC; (2) issued a postmarketing requirement to repeat the confirmatory trial (design as yet unknown); and (3) allowed the 960-mg dose to remain the labeled dose moving forward.10 Although we agree with decisions (1) and (2), we believe the scientific evidence continues to favor the 240-mg dose and advise oncologists to consider prescribing (off-label) the 240-mg dose.

In this case, the FDA may have lacked authority to require a change of the labeled dose prior to full regulatory approval. The alternative—to remove the drug from the market altogether—was likely considered and rejected. Given the pharmaceutical industry’s history of selectively reporting the contents of nonpublic complete response letters11 as well as the exemption of complete response letters from Freedom of Information Act requests,12 this case should spur a renewal of efforts to increase decision-making transparency at the FDA.13 Given the new postmarketing requirement and the public health imperative to provide patients with KRAS G12C–mutant NSCLC with the safest drugs, we urge the sponsor to release the complete response letter in full, so oncologists and patients can make informed decisions with full information.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Strohbehn is an employee of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; the views expressed do not reflect those of the U.S. federal government; he has received consulting fees from EBSCO Information Systems and VIVIO Health; is a co-inventor in a filed method-of-use patent in dose optimization (held by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the University of Michigan, for which he receives no royalties); and is a co-inventor (with M.R.) in a filed method-of-use patent in dose optimization of tocilizumab for viral infections (held by the University of Chicago, for which they receive no royalties). Dr. Lichter reported consulting fees from Cellworks and Ascentage Pharma. Dr. Ratain owns stock in SAB Biotherapeutics; has received honoraria from Emerald Lake Safety; has held a consulting or advisory role with Apotex, EQRx, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Cerona Therapeutics, T3 Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma, Halozyme, and Oscotec; has received research funding from AbbVie and Xencor; has received royalties related to UGT1A1 genotyping for irinotecan; has a provisional patent application for method of treating viral pneumonitis with low-dose tocilizumab; and has provided expert testimony for multiple generic companies (defendants in patent litigation). All authors are Directors of the Optimal Cancer Care Alliance.

REFERENCES

2. Amgen, Inc: 2022 Q3 earnings call transcript. Available at https://capedge.com/transcript/318154/2022Q3/AMGN [login required]. Accessed November 4, 2022.

4. De Langen AJ, Johnson ML, Mazieres J, et al: Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRASG12C mutation: A randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401:733-746, 2023.

5. Rddad Y: ODAC says PFS not interpretable endpoint for NSCLC drug sotorasib. OBR Oncology, October 5, 2023. Available at www.obroncology.com/article/odac-says-pfs-not-interpretable-endpoint-for-nsclc-drug-sotorasib. Accessed December 19, 2023.

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval letter to Amgen. Available at www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2021/214665Orig1s000ltr.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2023.

9. Amgen Provides Regulatory Update on Status of Lumakras (sotorasib). Amgen, December 26, 2023. Available at https://www.amgen.com/newsroom/press-releases/2023/12/amgen-provides-regulatory-update-on-status-of-lumakras-sotorasib. Accessed January 29, 2024.

10. Serani S: FDA rejects sNDA for sotorasib in KRAS G12C-mutated NSCLC. Targeted Oncology, January 2, 2024. Available at https://www.targetedonc.com/view/fda-rejects-nda-for-sotorasib-in-kras-g12c-mutated-nsclc. Accessed January 29, 2024.

11. Lurie P, Chahal HS, Sigelman DW, et al: Comparison of content of FDA letters not approving applications for new drugs and associated public announcements from sponsors: Cross sectional study. BMJ 350:h2758, 2015.

12. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services: Applications for Approval to Market a New Drug; Complete Response Letter; Amendments to Unapproved Applications. Federal Register: Vol. 73, No. 133, July 10, 2008. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2008-07-10/pdf/E8-15608.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2024.

Dr. Strohbehn is Clinical Assistant Professor at Rogel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Lichter served as Chair and Professor of Radiation Oncology at the University of Michigan from 1984 to 1998; Dean of the University of Michigan Medical School from 1998 to 2006; and Chief Executive Officer of ASCO and Conquer Cancer: the ASCO Foundation, from 2006 to 2016. Dr. Ratain is Chief Hospital Pharmacologist, University of Chicago Medicine.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.