A study by researchers at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and The Ohio State University in Columbus of whole-genome sequencing on patients found to have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations as well as on those who were not carriers of a BRCA1/2 mutation has found cancer risk of potentially pathogenic variants in the non-BRCA patients. Although the study results, published online in EBioMedicine,1 highlight the potential for improving risk assessment in patients with a family history of cancer, they also raise concerns over how best to counsel them.

“Right now, performing whole-genome sequencing in the cancer genetics clinic is inappropriate, but ultimately this is what is going to happen,” said Theodora Ross, MD, PhD, Professor of Internal Medicine and Director of the Cancer Genetics Program at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and corresponding author of the study. She emphasized, however, that since there is the potential to identify not only genetic risks for the patient’s primary diagnosis, but also risks for other conditions, “genetic counseling is so important” for patients.

Study Details

The researchers recruited 258 individuals from the cancer genetics clinics of The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and The Ohio State University cancer genetics programs. The researchers took blood samples from the patients and performed whole-genome sequencing on members of two cohorts of patients: those with BRCA1 (n = 88) or BRCA2 (n = 88) mutations and those who were not carriers of a BRCA1/2 mutation (n = 82). The genomes of 176 unrelated BRCA carriers at high risk for breast and ovarian cancers were first investigated to determine whether whole-genome sequencing confirmed the clinically diagnosed mutations.

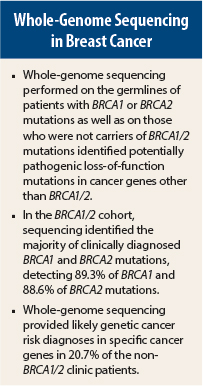

In the BRCA1/2 cohort, the researchers found that whole-genome sequencing correctly identified the majority of clinically diagnosed BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, detecting 89.3% of the BRCA1 mutations and 88.6% of the BRCA2 mutations. Initial analysis of potentially pathogenic variants in 163 other clinically relevant genes suggested that whole-genome sequencing would provide added useful clinical results.

Loss-of-function variants represented only a small fraction of potentially pathogenic variants. However, after the researchers expanded their analysis to 3,209 genes, whole-genome sequencing identified additional cancer risk, loss-of-function variants, and potentially pathogenic variants in patients with known BRCA1/2 mutations. This finding also led to diagnoses of cancer risk in 21% of the non-BRCA patients.

In total, reported the researchers, whole-genome sequencing provided likely genetic cancer risk of potentially pathogenic variants in 20.7% of the non-BRCA1/2 clinic patients. In contrast, according to the study abstract, “A recent report using targeted gene panel testing provided similar cancer risk of potentially pathogenic variants in 10.6% of non-BRCA1/2 patients.”

“There are other major challenges involved in translating whole-genome sequencing into the clinic, including questions of mutation penetrance, better understanding of the genes about which we understand little, and how to counsel patients who test negative or positive for an identified familiar mutation in one of the less well understood genes (CHEK2, PALB2, and RAD51C are good examples of this),” wrote the study authors.

Next Steps

The researchers are submitting their whole-genome sequencing data to the National Center for Biotechnology Information database of genotypes and phenotypes repository, so other investigators can do their own analyses and publish their findings, said Dr. Ross. She also hopes to perform parallel whole-genome sequencing on the more than 2,000 patients who come into The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s cancer genetics clinic for testing each year. In addition, Dr. Ross plans to use whole-genome sequencing to evaluate “mystery” patients—those with cancer-susceptibility syndromes but no known genetic defect—to attempt to identify candidate cancer genes.

Most important, said Dr. Ross, is to make the study of single genes a top research priority. “The problem is there is not enough basic science being done on the newly discovered genes in the genome. We are finding all of these broken open reading frames, and few are doing the basic and creative research needed to understand these ‘new’ gene products’ purposes in the normal cell,” she said. ■

Disclosure: The study authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Foley SB, Rios JJ, Mgbemena VE, et al: EBioMedicine (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.12.003.