Regulations that are developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must have some shelf-life before revisions are considered. The FDA has several mechanisms to provide patients with more rapid access to medicines. One such pathway is accelerated approval.

Backward Glance at Accelerated Approval Pathway

The accelerated approval pathway was developed in the early 1990s in response to the crisis caused by human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency disease (HIV/AIDs)1 and is based on the use of surrogate markers for FDA drug approval. This approach was developed after scientists determined that CD4 cell counts were a reliable surrogate outcome marker for evaluating the effectiveness of antiviral medications treating individuals with HIV/AIDS. In the 1992 FDA regulation that established the accelerated approval pathway, the regulation stipulates that a drug must address serious or life-threatening illnesses and fill unmet medical needs.

Charles L. Bennett, MD, PhD, MPP

Jeromie Ballreich, PhD, MHS

Drugs that receive the FDA accelerated approval designation using surrogate endpoints are required to demonstrate clinical benefit through a confirmatory phase IV clinical trial in most cases or, in the setting of rare diseases, with prospective registry programs. Although accelerated approval is an important pathway to bring new products to market, it has been criticized as setting low standards governing market entry and as a route where payers incur expenditures for products or indications that the sponsor or the FDA ultimately withdraw.

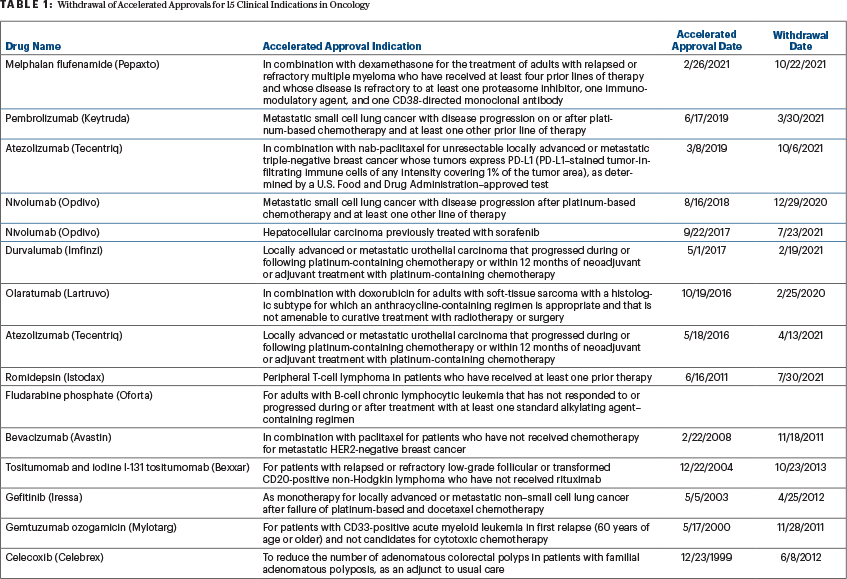

Select Withdrawals of Cancer Approvals

To date, sponsors have withdrawn cancer approvals for 15 clinical indications (Table 1). In 2021 alone, confirmatory phase IV clinical trials failed to demonstrate clinical benefit for 10 drug indications that had received accelerated approval by the FDA. Sponsors voluntarily discontinued marketing four drugs for accelerated approved indications that were not confirmed in phase III clinical trials. The FDA’s Oncology Drug Advisory Committee (ODAC) subsequently reviewed clinical data for the remaining six indications. ODAC recommended that sponsors should continue marketing drugs for four of the six accelerated approved indications, despite the failure of the phase IV clinical trials including interim analysis, and suggested that sponsors discontinue marketing drugs for two accelerated approved indications.

A team of researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg University School of Public Health, the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of South Carolina, funded by Arnold Ventures, quantified U.S. Medicare expenditures for atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody conditionally approved for malignant urothelial neoplasms in October 2016.1

They identified 14,182 Medicare fee-for-service claims for atezolizumab for 2018 and 2019, of which 8.8% were for second-line treatment of malignant urothelial carcinoma, representing 157 unique beneficiaries. The average cost to Medicare per claim was $6,854 (standard deviation [SD] = $1,843), whereas the average beneficiary coinsurance was $1,724 (SD = $1,325) per claim. Extrapolating our 20% sample to the full Medicare fee-for-service population, they estimated that in 2018 and 2019, there were approximately 6,200 paid claims representing $46 million for atezolizumab for an indication that was ultimately withdrawn due to a lack of confirmed evidence of clinical benefit.

Medicare Spending in Settings With Unconfirmed Clinical Benefit

This is the first study reporting on Medicare expenditures for an oncology indication where clinical trials failed to identify benefit. Although the FDA’s accelerated pathway is designed to bring products to the marketplace faster, this pilot study documents the wasted spending for a drug that ultimately fails to demonstrate clinical benefit.

“In 2021 alone, confirmatory phase IV clinical trials failed to demonstrate clinical benefit for 10 drug indications that had received accelerated approval by the FDA.”— Charles L. Bennett, MD, PhD, MPP, and Jeromie Ballreich, PhD, MHS

Tweet this quote

In this pilot project, the researchers found that a single health insurance payer—the U.S. Medicare program—spent -nearly $50 million over 2 years on one of these products that was administered in a clinical setting where clinical benefit was not confirmed. It is worth noting that the analysis assessed only the potential direct economic costs of pharmaceutical expenditures, although many other costs are also incurred by patients. Other important considerations are the opportunity costs of alternative, foregone treatments and potential financial and chemical toxicities of atezolizumab treatment.

A research group from Harvard Medical School, the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, and the Department of Health Policy at the London School of Economics subsequently reported on estimated Medicare spending for 10 oncology drug indications that had a confirmed lack of clinical benefit after receiving FDA accelerated approval.2 Between 2017 and 2019, they estimated that Medicare spending on the 10 indications increased to an estimated inflation-adjusted $569 million, of which $171 million corresponded to indications voluntarily withdrawn by manufacturers and $398 million corresponded to indications reevaluated by the FDA. The four indications that ODAC voted in 2021 to retain accounted for $345 million.

Policy Considerations

These findings raise two important policy considerations. First, who should ultimately bear the economic costs of treatments that receive accelerated approval for clinical indications but are ultimately withdrawn or rescinded due to failure to produce confirmatory clinical evidence? Policy alternatives proposed by the researchers include prospective and retrospective discounts that are operationalized when confirmatory trials are unsuccessful, manufacturing plus markup pricing for drugs during the time that clinical benefit is not confirmed or abiding by economic impact analyses that limit payers’ financial exposure to drugs used for cancer indications that have unconfirmed benefits. In this pilot study, the policy researchers proposed that manufacturers might refund the Medicare program some or all the atezolizumab revenues incurred for the withdrawn oncology indication.

“Who should ultimately bear the economic costs of treatments that receive accelerated approval for clinical indications but are ultimately withdrawn or rescinded due to failure to produce confirmatory clinical evidence?”— Charles L. Bennett, MD, PhD, MPP, and Jeromie Ballreich, PhD, MHS

Tweet this quote

A more overarching concern relates to the timing of confirmatory trials and response by the FDA when trials are delayed or failed to confirm clinical benefit. Although atezolizumab failed its originally designated confirmatory trial in May 2017, it remained on the market for the nonconfirmed clinical indication until 2021.

Second, the FDA should consider withdrawing approvals for oncology indications that fail to have confirmed clinical benefit. This could lower health-care expenditures by billions of dollars. The accelerated approval pathway, begun in 1992, is an ideal candidate for a reset in 2022. (For more on the withdrawal of cancer accelerated approvals, visit https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/withdrawn-cancer-accelerated-approvals.)

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Bennett reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ballreich has received grants from Arnold Ventures.

REFERENCES

1. Ballreich J, Bennett C, Moore TJ, et al: Medicare expenditures of atezolizumab for a withdrawn accelerated approved indication. JAMA Oncol 7:1720-1721, 2021.

2. Shahzad M, Naci H, Wagner AK: Estimated Medicare spending on cancer drug indications with a confirmed lack of clinical benefit after US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval. JAMA Intern Med 181:1673-1675, 2021.

Dr. Bennett is Professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Outcomes Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of South Carolina, Columbia. Dr. Ballreich is Assistant Scientist, Department of Health Policy & Management and Johns Hopkins Drug Access and Affordability Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.