Vincent T. DeVita, MD

George P. Canellos, MD

Medical oncology had a turbulent beginning, as we explained in part 1 of this commentary published in the September 25, 2024, issue of The ASCO Post. And although no other specialty we know of struggled as much, with perseverance and time, it had become a stable specialty of internal medicine by 1980. At this point in time, the major problem was how to marshal available resources to freely test the myriad opportunities presented by combination chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, especially if used together in novel ways. Here in part 2, we continue our discussion with the development of novel treatment protocols and the founding of ASCO in the 1960s.

Novel Protocols

Reason and optimism were introduced in protocol design by Howard Skipper, PhD, a biomathematician at Southern Research Institute in Birmingham, Alabama, who called himself the country’s mouse doctor and who was modeling treatment approaches in rodents bearing L1210 and other drug-sensitive tumors under contract with the CCNSC.1 Using the L1210 model, he was able to quantify cell kill by chemotherapy for both single drugs and combinations to optimize therapy. By 1964, he reported the cure of L1210 in the CDF1 mouse with combination chemotherapy—the first reported cure of a mouse leukemia.2

Using different mouse models with drug-sensitive tumors, Dr. Skipper also reported there was an invariable inverse relationship between cell number at the start of therapy and curability. This “inverse rule” would be a strong impetus for adjuvant drug treatment.3 He was a weekly visitor to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in those days, and his reports had a significant impact on the institute’s protocol design.

The use of drugs in combination in humans was, however, anathema in internal medicine. Even some prominent cancer investigators such as Sidney Farber, MD, spoke against using cancer drugs in combination. In general, the cooperative groups were content with testing single agents one by one.

Encouraged by Dr. Skipper’s work, Emil “Tom” Frei III, MD, and Emil J Freireich, MD, had been experimenting with two-drug combinations of methotrexate and mercaptopurine, with promising results and were anxious to expand this work. They were members of Acute Leukemia Group B (ALGB, which later became Cancer and Leukemia Group B) and were expected to use ALGB protocols. But the use of these protocols on a large scale was initially vetoed as too risky for a loosely connected group of clinical investigators. Drs. Frei and Freireich asked for and received an exemption from ALGB studies from C. Gordon Zubrod, MD, based on the unique resources available to accrue and support patients at the NCI.

They then developed the VAMP regimen (vincristine, methotrexate, mercaptopurine, and prednisone). The complete remission rate after VAMP in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was 60%, but this time, remissions were durable after induction with VAMP and no further treatment. They were measured in years and compatible with cure. The VAMP study had just 25 patients and was published in abstract form only at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting in 1964,4 but because of the existence of the cooperative group program, its results could be rapidly tested.

James Holland, MD, of Roswell Park Memorial Institute and Chairman of ALGB, rapidly steered that cooperative group into testing its own versions of combination chemotherapy, as did Don Pinkel, MD, of St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital,5 and Joseph Burchenal, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, all with similar results.6

By 1970, it was widely accepted in the field that pediatric ALL was a curable disease using combination chemotherapy, with all the programs needed to support heavily treated patients and developed in parallel, such as platelet transfusions, laminar airflow rooms, and multiple new antibiotics.

Introduction of MOPP

What about solid tumors? The model chosen for solid tumors in adults was Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), which was incurable when in an advanced stage in 1963. It responded to mechlorethamine with brief remissions that were most often incomplete. If the inverse rule applied, then HL would also have an advantage, since a minority of cells in an involved node were malignant Reed-Sternberg cells.

In 1965, VTD and John Moxley, MD, reported the results of a small study of four drugs—mechlorethamine, vincristine, methotrexate, and prednisone (MOMP)—given for the then-standard 6 weeks, in cyclical fashion to assess toxicity.7,8 The patients were initially treated in reverse isolation rooms. The complete remission rate was high, but the small nature of the study prevented drawing any conclusions about effectiveness. The toxicity was tolerable.

Methotrexate was not known to be an active drug in lymphomas, so in late 1965, procarbazine (then called ibenzmethyzin) was substituted for methotrexate, as the NCI’s phase II data on procarbazine became available.9 The drug showed unique activity in HL, and the length of therapy was adjusted to an unprecedented 6 months. The regimen was named MOPP.10,11

The MOPP protocol had an unusual design and was a radical departure from all the norms of the day. Acute leukemia regimens like VAMP were designed to treat until leukemia cells were ablated in the marrow and support the patient until normal marrow recovered. But in HL, the marrow wasn’t often involved, and the therapy needed to be given in a way to protect the bone marrow. Cell kinetic data from marrow, L1210 cells, and tumor of the breast involving the skin using tritiated thymidine12-14 showed that a mouse bearing L1210 was likely not a good model for humans with solid tumors. The growth fraction of L1210 was an unusual 100%, whereas human solid tumors had a growth fraction of around 25%. Although these data informed protocol design, transforming the data to the malignant cell in HL was guesswork, but if its cell kinetics resembled other solid tumors, longer periods of treatment in humans would be necessary. And it would need to be given at intervals wide enough to allow bone marrow recovery between cycles yet tight enough to prevent tumor growth between cycles—hence, the unique schedule used in MOPP.

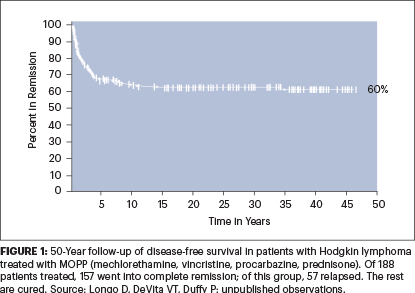

Because of the opportunity at NCI to recruit previously untreated patients from all over the United States, they were able to assemble a group of 43 previously untreated patients with advanced HL in a relatively short period. The results with MOPP were the best ever reported for a solid tumor, with 80% complete remission, with the majority staying in remission beyond 4 years after six monthly cycles of MOPP and no further treatment. Toxicity was significant but tolerable.11

By 1970, when the results in the first 43 patients were published with an average 4-year follow-up with few relapses, it was clear that HL was curable with MOPP. The results were soon confirmed in the United States and abroad. And now, with a 50-year follow-up of the expanded MOPP study of 188 patients at NCI, the results have held up (Figure 1).

The MOPP program was severely criticized within the NCI itself as too risky and interfering with other ongoing single-agent trials in lymphoma, with calls to cease and desist. Only the intervention of the visionary Tom Frei saved the day.

Within a decade, the mortality from childhood leukemia and HL declined in the United States by more than 70%. In 1975, the NCI group also reported the cure of advanced diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using a protocol called C-MOPP, which substituted cyclophosphamide for mechlorethamine in MOPP.15

Promise Fulfilled

To this day, combinations of drugs, each of which has a significant individual antitumor effect in a specific tumor, using the principles for drug selection, dose reduction, and scheduling laid down in the original MOPP protocol, are superior to single agents whether they are chemotherapies or immunotherapies or mixtures of both.

The NCI clinical center programs had fulfilled their promise. Proof of principle that malignant diseases could be cured using clever combinations of antitumor agents was in hand. Advanced HL was the first example of a curable advanced cancer of a major organ system in an adult. Childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia was a curable pediatric tumor. In 1972, many of the physician-scientists involved in the cures of these cancers received the Albert and Mary Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award.

The mood of oncologists improved everywhere, as MOPP represented a paradigm shift in cancer treatment. Practicing physicians could offer more than hope, and investigators began to pursue other ways to use combination chemotherapy.

Enter ASCO

All specialties eventually feel the need for a dedicated society. In 1964, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) was formed.

A group of seven adventurous physicians (Harry Bisel, MD; Arnoldus Goudsmit, MD, PhD; Fred Ansfield, MD; Robert Talley, MD; William Wilson, MD; Herman Freckman, MD; and Jane Cooke Wright, MD) invited a group of like-minded chemotherapists to meet, in conjunction with the AACR at its Annual Meeting. A total of 51 physicians (including the authors) attended the meeting, and the outlines of the new society with a greater focus on clinical programs was agreed upon.

Another meeting of 71 individuals was held in 1965, and ASCO was born. Dr. Bisel became the first President and Dr. Wright, the first treasurer. Since then, it has been the major organization advocating for support of clinical research and the care and well-being of physicians and patients in all the clinical cancer specialties.

Investigators now had a place to present and hear all major new clinical information. The Society journal (Journal of Clinical Oncology) has become the major source of information on advances in the field. From a meeting of 51 physicians, the ASCO Annual Meetings have grown to between 35,000 and 40,000 by the time of the 2024 meeting.

The Society also relentlessly pursued the goal of medical oncology’s designation as a subspecialty of internal medicine. One member, the late B.J. Kennedy, MD, of the University of Minnesota, deserves special kudos for his dedication to this goal.

In 1973, the American Board of Internal Medicine agreed to establish medical oncology as a specialty of internal medicine. In 1974, the first certification boards were given. Medical oncology had a home and a future.

Surge of Resources

Another momentous event occurred in the early 1970s, which altered the landscape of cancer research and treatment dramatically.16

In the late 1960s, the intrepid Mary Lasker, excited by the new information on cancer treatment, was convinced that cancer might be curable by the time of the U.S. bicentennial if a national effort to eradicate cancer was launched by the federal government. She gathered a group of like-minded lay people and scientists to persuade the Senate to pass a resolution to assemble a panel of consultants to review the potential for a “war on cancer.” The resolution passed unanimously, and the panel recommended they go forward; Congress passed the National Cancer Act of 1971, and President Richard Nixon signed the act into law on December 23, 1971, as a Christmas gift to the nation.

Its mandate was “to support research, and the application of the results of research, to reduce the incidence, morbidity, and mortality from cancer.” It was the first time an institute of the National Institutes of Health was mandated to support the application of the results of research, and it was not warmly received. No timeline for success was written into the act. Since then, although cancer has not been eradicated, its incidence, morbidity, and mortality have been significantly reduced.

The NCI budget went from $181 million in 1971 to $1 billion in 1980. A total of 85% of the budget went to laboratory-related research, and 15% went to clinical research including the clinical trials program. The budget for clinical trials went from $8 million in 1971 to $119 million in 1980.

The surge of resources couldn’t have come at a better time. With evidence that drugs could cure cancer, the use of chemotherapy as an adjunct to surgery, which would require large-scale clinical trials, now received special attention. At the NCI, the authors (GPC and VTD) developed the CMF program (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil)17,18 and tested it in advanced breast cancer, achieving a surprising 20% complete remission rate.17 Its cyclical design mimicked the MOPP protocol and made it ideal for outpatient adjuvant therapy of breast cancer.

The NCI did not have access to sufficient patients with breast cancer after surgery to do the large trial required. Paul Carbone, MD, Chief of NCI’s Medicine Branch at the time, approached major centers in the United States about collaborating on a large clinical trial of adjuvant CMF in stage II breast cancer. They all declined for fear of using a combination of toxic drugs in this population, some of whom would remain disease-free without therapy.

Dr. Carbone then approached a major breast cancer center in Europe, the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, led by the famous breast surgeon Umberto Veronesi, MD. Both Dr. Veronesi and his right-hand man Gianni Bonadonna, MD, agreed to run the trial, subject to a thorough review by Dr. Bonadonna of the CMF protocol and the early results. After a week at the NCI and some minor dose reductions, Dr. Bonadonna approved the trial.

In the meantime, Dr. Carbone convinced Bernard Fischer, MD, Director of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP, now the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project), to test a single oral alkylating agent L-phenylalanine mustard (L-PAM, subsequently known as melphalan) as an adjuvant to surgery. The NSABP, a highly motivated group of mostly breast cancer surgeons, rapidly accrued patients to the melphalan study and published their results in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 1975. Dr. Bonadonna and colleagues followed suit and published their CMF results in NEJM in 1976. Both studies were positive, with CMF having a greater effect in preventing recurrences.19,20 Both studies were firsts in the field.

The excitement over the results of these landmark studies was enhanced by the diagnosis of breast cancer in the wives of the President and Vice President of the United States. This sparked a national discussion about eligibility for the treatment (Betty Ford received melphalan, Happy Rockefeller declined adjuvant treatment).

These results set off a cascade of adjuvant trials in a multitude of tumors. Today, two-thirds of the reduction in mortality from breast cancer in the United States is from the successful application of adjuvant therapy.

We ended the 1970s with the report by Lawrence Einhorn, MD, and colleagues of another tumor, metastatic testicular cancer, succumbing to a cyclical combination chemotherapy program.21

The Coming Revolution

Still to come was the exciting molecular revolution created by the massive funding for research in molecular biology by the National Cancer Program. Proof of principle that the immune system can be harnessed to cure some fraction of many types of cancer is in hand22; molecular targets created by mutations in cancer cells can be successfully attacked; autologous lymphocytes can be genetically modified to serve as a drug to attack a variety of cancers. And the list goes on.

It’s still a rough and tumble road, but the bumps in the road are now opportunities, and optimism has replaced pessimism as the prevailing mood.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. DeVita and Dr. Canellos reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Skipper HE, Schabel FM Jr, Mellet LB, et al: Implications of biochemical, cytokinetic, pharmacologic and toxicologic relationships in the design of optimal therapeutic schedules. Cancer Chemother Rep 54:431-450, 1950.

2. Skipper HE, Schabel FR Jr, Wilcox WS: Experimental evaluation of potential anticancer agents. XII. On the criteria and kinetics associated with ‘curability’ of experimental leukemia. Cancer Chemother Rep 35:1-111, 1964.

3. Schabel FM: Concepts for systemic treatment of micrometastases. Cancer 35:15, 1975.

4. Freireich EJ, Karon M, Frei E III: Quadruple combination therapy (VAMP) for acute lymphocytic leukemia of childhood. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 5:20, 1964.

5. George P, Hernandez K, Hustu O, et al: A study of total therapy of acute lymphocytic leukemia in children. J Pediatr 72:399-408, 1968.

6. Burchenal JH: Treatment of leukemias. Semin Hematol 31:122, 1966.

7. DeVita VT, Moxley JH, Brace K, et al: Intensive combination chemotherapy and X-irradiation in the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 6:15, 1965.

8. Moxley JH III, DeVita VT, Brace K, et al: Intensive combination chemotherapy and X-irradiation in Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Res 27:1258-1263, 1967.

9. DeVita VT, Serpick A, Carbone PP: Preliminary clinical studies with ibenzmethyzin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 7:542-546, 1966.

10. DeVita VT, Serpick A: Combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 8:13, 1967.

11. DeVita VT, Serpick AA, Carbone PP: Combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Intern Med 73:881-895, 1970.

12. Young RC, DeVita VT: Cell cycle characteristics of human solid tumors in vivo. Cell Tissue Kinet 3:285-290, 1970.

13. Young RC, DeVita VT: The effect of chemotherapy on the growth characteristics and cellular kinetics of leukemia L1210. Cancer Res 30:1789-1794, 1970.

14. Yankee RA, DeVita VT, Perry S: The cell cycle of leukemia L1210 cells in vivo. Cancer Res 27:2381-2385, 1967.

15. DeVita VT, Canellos GP, Chabner B, et al: Advanced diffuse histiocytic lymphoma, a potentially curable disease: Results with combination chemotherapy. Lancet 1:248-254, 1975.

16. DeVita VT: A perspective on the war on cancer. Cancer J 8:352-356, 2002.

17. Canellos GP, DeVita VT, Gold GL, et al: Cyclical combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced breast carcinoma. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 15:148, 1974.

18. Canellos GP, DeVita VT, Gold GL, et al: Cyclical combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced breast carcinoma. Brit Med J 1:218-220, 1974.

19. Fisher B, Carbone P, Economou SG, et al: L-phenylalanine mustard (L-PAM) in the management of primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med 292:110-122, 1975.

20. Bonadonna G, Brusamolino E, Valegussa P, et al: Combination chemotherapy as an adjunct treatment in operable breast cancer. N Engl J Med 294:405-410, 1976.

21. Einhorn LH, Donohue J: Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, vinblastine, and bleomycin combination chemotherapy in disseminated testicular cancer. Ann Intern Med 87:293-298, 1977.

22. Tran E, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA: ‘Final common pathway’ of human cancer immunotherapy: Targeting random somatic mutations. Nature Immunol 18:255-262, 2017.

Dr. DeVita is the Amy and Joseph Perella Professor of Medicine and Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at Yale Cancer Center. He has served as Director of Yale Cancer Center (1993–2003), Director of the NCI and the National Cancer Program (1980–1988), and President of ASCO (1977–1978). Dr. Canellos is a senior physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He is the former Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Clinical Oncology (1988–2001) and President of ASCO (1993–1994).