In this installment of the Living a Full Life series, Guest Editor Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, spoke with Stanton (“Stan”) L. Gerson, MD, Dean and Senior Vice President for Medical Affairs, School of Medicine, and Acting Director of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center and National Center for Regenerative Medicine at Case Western Reserve University, where he is the Asa and Patricia Shiverick–Jane Shiverick (Tripp) Professor of Hematological Oncology and Case Western Reserve University Distinguished University Professor.

STANTON L. GERSON, MD

On his career-long affiliation with Case Western: “I’ve had great opportunities here, and I’ve cherished the open academic freedom that has allowed my career to grow in different directions.”

On modern medical education: “I’m realizing that in this day and age, you can’t train medical students in an abstract environment. It must be done within the public health community, dealing with issues that are timely.”

On ‘tribalism’ in patient care and community interactions: “Understanding different orientations and perspectives influences every element of medicine, so naturally, we have to be aware of the human phenomenon in order to find common ground.”

Dr. Gerson grew up in Lincoln, a small town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, which has a rich colonial history. “Lincoln is an ancient town by U.S. standards. It was incorporated in the 1750s, and its claim to fame consists of two things: First, it’s where Paul Revere was captured, and therefore the revolutionary war was central. In fact, I read the Declaration of Independence on July 4th every year. And second, it is the site of a small museum called deCordova, situated on the shore of Flint’s Pond, which is recognized for its sculpture garden and is like a halo for that region. I grew up in a world populated by professorial types from Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston University, and Tufts,” said Dr. Gerson.

He continued: “My father was a physicist who worked for the National Security Agency. For 60 years, I never knew what he did until there was a book written about it. However, when our family vacationed in Puerto Rico for 3 years in a row and stayed at a U.S. Air Force base because my father was busy tuning the new radio telescope at Arecibo (so it could receive radio signals from the other side of the world), I realized that he didn’t have an ordinary job. It was the 1960s during the Cold War, and my father did a lot of ‘listening’ to the Russians using a form of transmission called ‘moon bounce,’ whereby the signal is reflected off the moon, so that it can be picked up on Earth wherever the moon is above the horizon. He eventually got credit for his work.”

He added: “My mother had been in the WAVES, and now she’s buried at Arlington National Cemetery. She grew up as the newspaper reporter for a small town, so whenever there was news, my mother was in the middle of it.”

Medicine Over Physics

Dr. Gerson attended Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School, a highly regarded regional public high school, which was established in 1954. “Being a physicist, my father got us involved in some pretty rigorous science projects in the basement, and my brothers and sisters and I received a number of National Science Foundation awards as high school scientists, which accelerated my interest in science.”

Asked why he didn’t follow in his father’s footsteps and become a physicist, Dr. Gerson remarked: “I actually went to Harvard, majored in physics, and took quantum mechanics in my sophomore year. However, fate intervened. This was 1970, and the Vietnam War was still very active. As engaged students, we participated in strikes and protests, including a bunch of semi-riots, during which police in full riot gear swarmed the campus at Harvard, which was a pretty amazing experience. We didn’t have final exams that year, and that meant that I could only receive a C-plus in quantum mechanics, and that was reason for concern. (I did have a colleague in that course who was a year younger, a guy named Sandy Markowitz, who did very well. He’s now a colleague here at Case Western and is an eminent researcher in gastrointestinal disease.) So I realized at that time that I better switch my major; I moved to biomedical sciences and did fine. That’s sort of the way I got out of physics and into medicine.”

A Career in Hematology Begins

In 1973, Dr. Gerson graduated magna cum laude from Harvard College and then entered Harvard Medical School, where he met his future wife. “I met Debbie on the first day of school. She’d gone to Yale,” he noted.

GUEST EDITOR

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

“In medical school, I became interested in hematology because I liked looking at slides and blood cells. I really became very comfortable in my ability to diagnose acute leukemia on blood smear. I worked with the head of that class, Steve Robinson, who was Chief of Hematology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. I actually did my first stem cell transplant in a mouse in 1975. And I still have a laboratory that does stem cell transplants. We’ve moved mountains in what we now study, but I’m still intrigued by stem cell biology and stem cell abnormalities,” said Dr. Gerson.

“We’ve confirmed that primary tumors and metastases can be very different in nature. Scientists have realized that perhaps there is a unique cell that causes cancer or its recurrence. With this premise in mind, we sought to identify characteristics of the cells within tumors, specifically looking for features that were rarely present, and why they took on special roles. Most of our cells—for example, skin or bone marrow cells—differentiate, slough off, and die. But a cancer stem cell can rest, which means it can lie dormant for days, months, or years. It can also replicate itself and divide many times. And those cells can spread to different locations and grow there…. It’s a fascinating line of inquiry.”

In 1980, Dr. Gerson began his hematology and oncology fellowship training at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. “Debbie and I matched at Penn as a ‘seriously other’ couple, which was the category if you weren’t married or engaged. We didn’t quite realize that ‘seriously other’ wasn’t meant for us, but instead for folks who were same-sex partners, but whatever.”

He continued: “At that time, Penn Cancer Center had a stellar lineup of hematologists and oncologists, including Drs. Buzz Cooper, John Glick, Dan Haller, Jane Alavi, Peter Cassolith, Janet Abram, Skip Brass, Dupont Guerry, Joel Bennett (who just passed away), and Sandy Shattil. And we got a lot done during a fairly short time. For instance, we had an outbreak of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and Peter Cassolith and I published a total of six papers on making the diagnosis, identifying risk factors, and something that was briefly called the ‘Gerson curve’ back in the day, which was the time course of prolonged cytopenia and the risk of developing aspergillosis in the lungs. The one describing that association is still one of my most frequently sited papers,” said Dr. Gerson.

First and Only Affiliation

In 1983, after completing his residency and hematology and oncology fellowship training at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Gerson joined the faculty at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where he has remained without interruption throughout his career—something that Dr. Abraham pointed out was unusual in academic oncology, where leaders in the field are regularly offered new opportunities. “Well, it’s funny, because I keep getting asked where my enemies are, and I do suggest that it’s harder to stay in one location than to switch institutions. But I’ve had great opportunities here, and I’ve cherished the open academic freedom that has allowed my career to grow in different directions. To me, success in medicine is keeping ahead of the fray, having good ideas, and synthesizing. My global perspective is: you take the winners and don’t worry about the loses—just try to mitigate whatever challenges there are,” said Dr. Gerson.

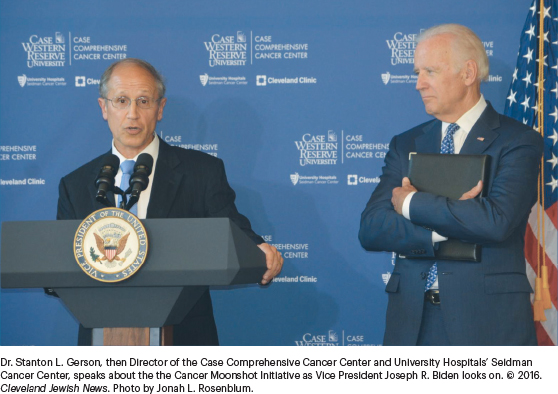

His leadership of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center involves coordinating research throughout the medical centers in Cleveland, including Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and Case Western Reserve University. He led University Hospitals’ effort to bring cancer care under one roof in a freestanding cancer hospital, the Seidman Cancer Center, which opened in June 2011. Dr. Gerson also led the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center to an “exceptional” National Cancer Institute (NCI) rating based on its outstanding accomplishments in genomics research; disease-focused cancer research in colon and esophageal cancers, leukemias, genitourinary malignancies, and breast and brain tumors; and its ability to rapidly bring the newest discoveries into clinical use for patient benefits.

In 2011, Dr. Gerson established the center’s first Community Advisory Board, which is developing engagements with the Cleveland community designed to improve access to cancer care and clinical trials, improve early cancer detection and screening, provide vaccinations against human papillomavirus, and help patients in need navigate from the community to cancer centers in Cleveland.

Challenges and Opportunities as Dean

On October 1, 2021, Dr. Gerson was named Dean of the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Asked about the position, he replied: “When I flipped over to being Dean, I was amazed at how unprepared I was for medical education. Now, I have two children who are physicians, so you’d think I’d get it by now, but I am just getting involved with medical education issues for our school of medicine, and I’ve got incredibly competent people around me.”

He continued: “I’m also realizing that in this day and age, you can’t train medical students in an abstract environment. It must be done within the public health community, dealing with issues that are timely. And to that end, we’re going to begin a set of conversations across our medical school, on such topics as attention to diversity, equity and systemic racism, the impact of medicine on climate change, the opioid addiction problem, the medical consequences of reducing access to abortion, and the public health consequences of gun control (and whether and how medicine should be involved in that debate). I feel these topics are part of my tradition of keeping ahead of the fray and moving new ideas forward.”

The Doctor’s Role

When the discussion moved into the thorny area of how the academic environment develops and controls the flow of information, Dr. Gerson offered his learned opinion: “When Francis Collins departed the scene as Director of the National Institutes of Health, he noted that he was challenged in disseminating medical information because of "tribalism". That was a really interesting concept. But I want to stay away from the politic and move it to the medical environment, with regard to how we handle the very sensitive areas of information dissemination,” he said.

“We all have an orientation and peculiar interest—a subgroup that we’re comfortable with, the community we interact with. I suppose that’s a passive form of tribalism; tribes are the nature of human existence, and we’re not going to do away with that imbedded orientation. So, as I teach or when I walk into a patient’s room or into a community I’m interacting with, it becomes necessary to quickly gauge an individual’s background, interests, and perspectives—what is this person’s tribe? It’s no different than the conversation about emotional intelligence, which is also about understanding the footsteps and the background of the individual you’re interacting with,” Dr. Gerson said.

He continued: “I think that understanding is absolutely essential in every walk of life, but particularly in medicine. Another thing I think we would agree on is that physicians interact with a broader range of the community than most other people. Navigating across that very broad community starts with the patient encounter, which is one of the most interesting and intimate interactions in life. And understanding different orientations and perspectives influences every element of medicine, so naturally, we have to be aware of the human phenomenon in order to find common ground.”

The Joy of Work

Dr. Abraham then asked: What still excites you, after such a long and fulfilling career? He replied: “Becoming Dean has allowed me to appreciate that the cancer center movement in this country is profound, unequaled by any other initiative in medicine. Moreover, the NCI oversight of cancer research and therapeutics as well as community engagement and education training is profoundly more successful than any other initiative. That said, for the most part, medical schools and hospitals are doing a superb job, but if you look at the movement, the coordination, and the interest of cancer centers around the country, it’s profoundly different.”

He explained: “For instance, I saw a new patient last week who lives north of Detroit, and I thought he needed radiation therapy. It would be almost a 3-hour drive for him to access that service. So, while I was in the patient room, I called Gerald Bepler, Director of the Karmanos Cancer Center in Detroit, who immediately got me on the phone with the head of radiation oncology, and within 5 minutes, we arranged for an appointment 2 days hence with radiation oncology in Detroit. I can call any cancer center director in the country and immediately get a referral. As Dean, I can’t do that vital medical networking, but I can do that as a cancer center director, which excites me to no end,” said Dr. Gerson.

How does a researcher and leader find balance and decompress? “I’m not sure there’s an answer to the balance. I mean, you do what you can, and you lose a little bit because you’re too sloppy and all that, but you balance it by being slightly distractable and keeping all the balls in the air. My spouse, who is recently retired, and I have always focused our life on the work we love, our home, and our three children, who are highly productive and successful. I guess you could say that our main distraction from work was physical exercise, and we have always had a pool in the backyard. I swim every morning when it’s not snowing, and we exercise, hike, and garden.”

Parting Thoughts

Finally, Dr. Abraham asked Dr. Gerson if he had any other words of advice for young oncologists, fellows, or students. He replied: “I think that listening, learning all the time, observing, and being resilient are the essential qualities for overall success. I’m going to conduct a special white coat ceremony for our year 3 medical students because they couldn’t get their usual ceremony due to the pandemic, and those are my four words: listening, learning, observation, and resilience.”

He added: “Regarding observation, the best physicians among us can do an essential diagnostic section of their physical exam by looking and using their carefully honed observation skills. When you meet a physician who can make a diagnosis from across the room, pay attention to that physician because it will enhance your career in subtle ways that will make you a far better doctor. The art of observation is very much underappreciated.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Gerson reported no conflicts of interest.