The ASCO Post is pleased to present the Hematology Expert Review, an ongoing feature that quizzes readers on issues in hematology. In this installment, Drs. Abutalib, Desai, and DeAngelis explore the treatment of older patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), which pose important practical challenges for clinicians. For each quiz question that follows, select the one best answer. The correct answers and accompanying discussions appear below.

Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Shreya Desai, MD

Lisa M. DeAngelis, MD

PCNSL is a rare and aggressive subtype of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that is confined within the craniospinal axis; it may involve brain parenchyma, vitreous, retina, cranial nerves, spinal cord, and leptomeninges. The 2016 World Health Organization definition of PCNSL excludes lymphomas of the dura, intravascular large B-cell lymphomas, secondary CNS lymphoma, and all immunodeficiency-associated lymphomas from this category. In the HIV infection context, CNS diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is an AIDS-defining illness with distinct characteristics compared with PCNSL in an immunocompetent host.1

PCNSL accounts for less than 1% of all NHLs and between 3% and 4% of all brain tumors, with an age-adjusted incidence rate of four cases per million persons per year.2 Approximately 1,500 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States; this rate is steadily increasing as the population ages, with nearly 50% of cases diagnosed in individuals older than age 60.3,4

Induction therapy with high-dose methotrexate is the single most notable advance in patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL. Following induction therapy, consolidation is given to deepen and maintain response.5-7 Most recently, the concept of maintenance therapy has been introduced, especially in patients who are deemed “frail” to receive consolidation. Overall, the treatment program of induction and consolidation attains cure in approximately 50% of patients,5-7 underscoring the fact that half of adult patients are still not cured. Whenever possible, all patients with PCNSL should be encouraged to enroll onto a well-designed clinical trial.

Question 1

Which of the following statements about age and the use of high-dose methotrexate in patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL is correct?

A. It should not be administered in patients older than age ≥ 60.

B. It should not be administered in patients older than age ≥ 65.

C. It should not be administered in patients older than age ≥ 70.

D. None of the above.

Question 2

Which statement about induction therapy in adults with PCNSL is correct?

A. The toxicity associated with whole-brain radiation therapy is comparable to that of high-dose methotrexate.

B. High-dose methotrexate induction is preferred over whole-brain radiation therapy.

C. Conventional whole-brain radiation therapy (45 Gy) alone results in prolonged remissions (> 2 years).

D. Outcomes are comparable between older and younger adults with the use of high-dose methotrexate–based regimens.

Question 3

Which of the following statements about the survival trends in PCNSL from 1973 to 2013 are correct?

A. Median overall survival of patients doubled during this period.

B. Median overall survival was approximately 12.5 months in the 1970s.

C. Survival benefit is seen in patients younger than age 70.

D. All of the above.

Question 4

The largest chemotherapy-alone trials in older adults with PCNSL are the multicenter single-arm PRIMAIN trial (patients ≥ 65 years) and an open-label randomized phase II trial conducted by the French ANOCEF-GOELAMS group (patients ≥ 60 years). Which of the following statements concerning these two trials is correct?

A. Neither trial accrued patients for maintenance therapy.

B. The rate of treatment-related deaths in both trials was 3%.

C. The ANOCEF-GOELAMS trial reported similar efficiency between the two experimental arms.

D. Neither trial enrolled patients for high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Question 5

Which of the following statements about maintenance therapy in PCNSL is correct?

A. In older adults who cannot tolerate consolidation therapy, maintenance treatment may be an alternative approach.

B. All maintenance agents or regimens are highly empirical in terms of optimal dose and schedule.

C. There is no randomized clinical trial in PCNSL proving that maintenance treatment is of benefit.

D. All of the above.

Answers to Hematology Expert Review Questions

Question 1

Which of the following statements about age and the use of high-dose methotrexate in patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL is correct?

Correct answer: D. None of the above.

Expert Perspective

The definition of “elderly” in PCNSL is nonuniform, and age should not be used as the sole determinant to exclude patients from highly effective chemotherapy such as high-dose methotrexate.5,6 Despite evidence that high-dose methotrexate offers a survival benefit in older adults with adequate organ function and good performance status, concerns of toxicity have led to decreased use of chemotherapy in this patient population.8,9

An analysis of the National Cancer Database Participant Use File Registry found that among patients between the ages of 61 and 70 who survive more than 3 months from diagnosis, 14.4% did not receive any chemotherapy.10 This fraction increased to 23.3% in patients between the ages of 71 and 80 and escalated to 44.1% in patients older than age 80.

Another recent retrospective analysis of the National Cancer Database11 evaluated non-HIV patients with PCNSL older than age 65 from 2004 to 2015 and found that 16% received no treatment. Moreover, according to a population-based Medicare study of 579 patients diagnosed with PCNSL from 1994 to 2002, age was inversely correlated with the chance of treatment with methotrexate, and up to 82% of patients 80 years or older received either whole-brain radiation therapy alone or no treatment at all.12 However, many older patients can tolerate and benefit from high-dose methotrexate–based regimens. Renal function and overall biologic age are more important determinants than chronologic age.

Question 2

Which statement about induction therapy in adults with PCNSL is correct?

Correct answer: B. High-dose methotrexate induction is preferred over whole-brain radiation therapy.

Expert Perspective

Most studies support the use of chemotherapy-alone treatments (induction and consolidation), especially in older adults, given the high risk of irreversible and debilitating neurotoxicity associated with chemotherapy combined with whole-brain radiation therapy.5-7 Whole-brain radiation therapy may induce a speedy remission, but disease recurrence is rapid, and median survival is only about a year. High-dose methotrexate combined with whole-brain radiation therapy prolongs disease-free survival but is associated with a high-risk of neurotoxicity, particularly in older adults. The neurotoxicity is irreversible and results in progressive cognitive dysfunction, ataxia, and urinary incontinence. Contrary to a combined approach of high-dose methotrexate and whole-brain radiation therapy, high-dose methotrexate alone has been shown to improve quality of life. Currently, whole-brain radiation therapy is a reasonable option in selected situations, such as a palliative approach in patients with relapsed or refractory PCNSL when other options are not available.7 When compared with that of younger adults, the prognosis of older adults is inferior regardless of the high-dose methotrexate–based regimen chosen.5-7

Question 3

Which of the following statements about the survival trends in PCNSL from 1973 to 2013 are correct?

Correct answer: D. All of the above.

Expert Perspective

Mendez et al4 utilized 2 national databases to examine survival trends over time for PCNSL: the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (2000–2013) and 18 registries from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (1973–2013). Even though the median survival of all patients doubled from 12.5 months in the 1970s to 26 months in the 2010s, this benefit was limited to patients younger than age 70. Survival in the older population has not changed in the past 40 years (6 months in the 1970s vs 7 months in the 2010s, P = .1). This could be explained by less aggressive treatment or even the absence of any treatment, poor functional status (an independent prognostic factor along with age), and more comorbidities in this patient population. It should be noted that high-dose methotrexate–based polychemotherapy regimens are not only effective and safe, but also improve quality of life in a significant proportion of older adults with PCNSL.13

Question 4

The largest chemotherapy-alone trials in older adults with PCNSL are the multicenter single-arm PRIMAIN trial (patients ≥ 65 years) and an open-label randomized phase II trial conducted by the French ANOCEF-GOELAMS group (patients ≥ 60 years). Which of the following statements concerning these two trials is correct?

Correct answer: D. Neither trial enrolled patients for high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Expert Perspective

In both trials, nonmyeloablative high-dose methotrexate–based polychemotherapy regimens were investigated. Here are highlights from these trials.

PRIMAIN trial (2017)14: Patients (n = 107) were treated with rituximab, high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine, and lomustine. Treatment was repeated every 42 days with three cycles. Maintenance treatment with procarbazine (six cycles repeated on day 29) was started on day 43 of the last rituximab, high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine, and lomustine cycle. Maintenance treatment was also allowed if all three rituximab, high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine, and lomustine cycles were not completed. After protocol amendment, lomustine was omitted, but the other immunochemotherapy components remained unchanged.

The complete remission rate after three cycles (primary endpoint) was 35.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 26.5%–45.4%). The complete remission rate was slightly lower in patients treated with rituximab, high-dose methotrexate, and procarbazine compared with rituximab, high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine, and lomustine (31.6% vs 37.7%). The median overall survival of the total cohort was 20.7 months, with overall survival rates after 1 and 2 years of 56.7% and 47.0%, respectively, with no difference between the treatment groups. Median progression-free survival was 10.3 months, with 1- and 2-year progression-free survival rates of 46.3% and 37.3%, respectively. Omitting lomustine from the regimen was associated with similar progression-free and overall survival with less overall toxicity. There was an 8% rate of treatment-related deaths.

Phase II randomized French ANOCEF-GOELAMS trial (2015)15: This study (n = 98) compared high-dose methotrexate plus temozolomide (n = 48) with high-dose methotrexate, prednisolone, vincristine, and cytarabine (n = 47). Response rates were 71% with high-dose methotrexate and temozolomide and 82% with high-dose methotrexate, prednisolone, vincristine, and cytarabine. The 1-year progression-free survival (primary endpoint) was 36% (95% CI = 22%–50%) in both treatment groups. Median progression-free survival was 6.1 months (95% CI = 3.8–11.9 months) and 9.5 months (95% CI = 5.3–13.8 months), respectively. The median overall survival was 14 months (95% CI = 8.1–28.4 months) and 31 months (95% CI = 12.2–35.8 months), respectively. Quality-of-life evaluation showed improvements in most domains (P = .01–.0001) compared with baseline in both groups. There was an 8% rate of treatment-related deaths.

Neither study examined the role of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, such an approach may be considered in carefully selected “biologically young” older adults with PCNSL.16 A recent single-arm pilot study by Schorb et al17 (n = 14) demonstrated that high-dose chemotherapy (busulfan in combination with thiotepa) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is safe and effective in older adults with PCNSL.

Question 5

Which of the following statements about maintenance therapy in PCNSL is correct?

Correct answer: D. All of the above.

Expert Perspective

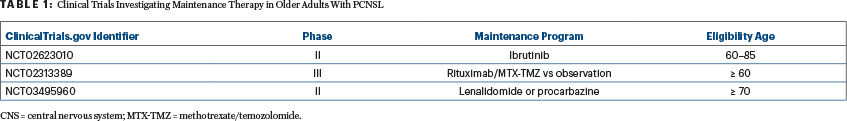

There are several ongoing studies evaluating the role of maintenance therapy in older adults with newly diagnosed PCNSL.6 Table 1 highlights some of the ongoing phase II and III studies.

Dr. Abutalib is Associate Director of the Hematology and BMT/Cellular Therapy Programs and Director of the Clinical Apheresis Program at the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Zion, Illinois; Associate Professor at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; and Founder and Co-Editor of Advances in Cell and Gene Therapy. Dr. Desai is Resident Physician, Internal Medicine, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois. Dr. DeAngelis is Physician-in-Chief, Chief Medical Officer, and Scott M. and Lisa D. Stuart Chair at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and Professor of Neurology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Abutalib has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca. Dr. Desai reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. DeAngelis has served as a consultant or advisor to Sapience Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

1. Kluin PM, Deckert M, Ferry JA: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS, in Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al (eds.): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, pp 300-302. Lyon, France, International Agency for Research in Cancer, 2017.

2. Villano JL, Koshy M, Shaikh H, et al: Age, gender, and racial differences in incidence and survival in primary CNS lymphoma. Br J Cancer 105:1414-1418, 2011.

3. Olson JE, Janney CA, Rao RD, et al: The continuing increase in the incidence of primary central nervous system non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Cancer 95:1504-1510, 2002.

4. Mendez JS, Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, et al: The elderly left behind: Changes in survival trends of primary central nervous system lymphoma over the past 4 decades. Neuro Oncol 20:687-694, 2018.

5. Ferreri AJM: How I treat primary CNS lymphoma. Blood 118:510-522, 2011.

6. Siegal T, Bairey O: Primary CNS lymphoma in the elderly: The challenge. Acta Haematol 141:138-145, 2019.

7. Grommes C, Rubenstein JL, DeAngelis LM, et al: Comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment of newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol 21:296-305, 2019.

8. Jahnke K, Korfel A, Martus P, et al; German Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Study Group: High-dose methotrexate toxicity in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Oncol 16:445-449, 2005.

9. Ng S, Rosenthal MA, Ashley D, et al: High-dose methotrexate for primary CNS lymphoma in the elderly. Neuro Oncol 2:40-44, 2000.

10. Fallah J, Qunaj L, Olszewski AJ: Therapy and outcomes of primary central nervous system lymphoma in the United States: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Blood Adv 1:112-121, 2016.

11. Samhouri Y, Ali MM, Jayakrishnan T, et al: Patterns of treatment and survival in elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma: An 11-year population-based analysis. Blood 136(suppl 1):2-3, 2020.

12. Panageas KS, Elkin EB, Ben-Porat L, et al: Patterns of treatment in older adults with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Cancer 110:1338-1344, 2007.

13. Welch MR, Omuro A, Deangelis LM: Outcomes of the oldest patients with primary CNS lymphoma treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Neuro Oncol 14:1304-1311, 2012.

14. Fritsch K, Kasenda B, Schorb E, et al: High-dose methotrexate-based immuno-chemotherapy for elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients (PRIMAIN study). Leukemia 31:846-852, 2017.

15. Omuro A, Chinot O, Taillandier L, et al: Methotrexate and temozolomide versus methotrexate, procarbazine, vincristine, and cytarabine for primary CNS lymphoma in an elderly population: An intergroup ANOCEF-GOELAMS randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2:e251-e259, 2015.

16. Schorb E, Fox CP, Fritsch K, et al: High-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: A European retrospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant 52:1113-1119, 2017.

17. Schorb E, Kasenda B, Ihorst G, et al: High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant in elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma: A pilot study. Blood Adv 4:3378-3381, 2020.