A pair of recent studies show a troubling trend: Despite a 20% decrease in cancer mortality rates nationwide over the past 2 decades,1 Americans living in rural regions of the United States are more likely to die of cancer than persons living in metropolitan areas of the country. An analysis of cancer rates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that although overall cancer incidence rates were a bit lower in rural areas—442 cases per 100,000 persons—than in urban areas—457 cases per 100,000 persons—they were higher for specific cancers common with tobacco use, such as lung and laryngeal cancers, and those that can be prevented through cancer screening, such as colorectal and cervical cancers, and vaccination for human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers, such as of the cervix, oral cavity, and pharynx. In addition, the CDC’s analysis found that mortality rates were higher in these rural communities—180 deaths per 100,000 persons—than in urban areas of the country—158 deaths per 100,000 persons.2

People in these communities are diagnosed at later stages, and the result is the 3- to 5-year survival rates are worse than in other parts of the country.— Nengliang (Aaron) Yao, PhD

Tweet this quote

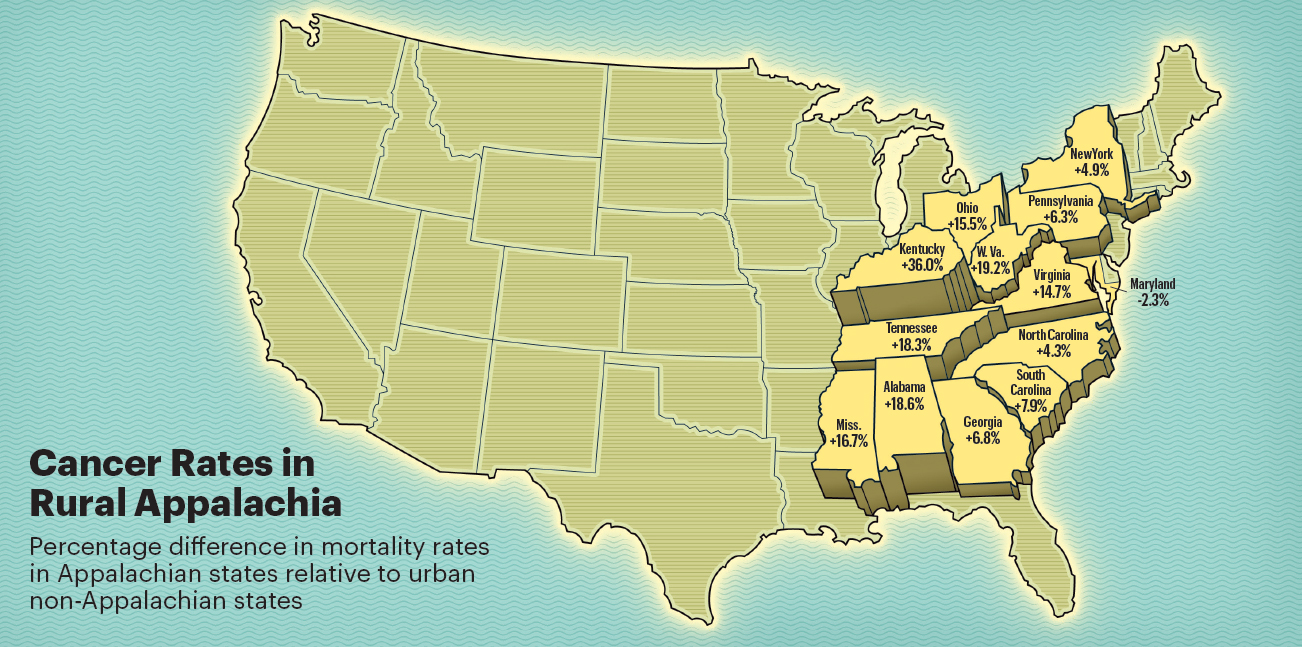

Another study paints an even dimmer cancer outlook for people living in rural Appalachia. Research by Nengliang (Aaron) Yao, PhD, Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, and his colleagues showed that between 1969 and 2011, cancer incidence declined in every region of the country except rural Appalachia, and the mortality rates soared. During those years, in rural Appalachian counties in Virginia, cancer death rates were nearly 15% higher than in non-Appalachian urban areas nationwide, 19% higher in those areas in West Virginia, and 36% higher in rural Appalachian counties in Kentucky.3 In addition, breast cancers were found at more advanced stages in women living in Appalachian states, and the 3- to 5-year survival rates for all cancers were lower compared with people living in urban non-Appalachian communities: 65% and 58% of all patients with cancer living in urban non-Appalachian regions survived for at least 3 and 5 years, respectively. Conversely, just 57% and 50% of patients living in rural Appalachia survived for at least 3 and 5 years, respectively.

“From the 1970s through the 1980s, the cancer mortality rates in rural Appalachia were the lowest in the country, and around the mid-1990s, when the national cancer death rates started to decline due to cancer screening programs, more effective oncology therapies, and better tobacco control, they started to increase in Appalachia,” said Dr. Yao.

A perfect storm of troubling events -transpiring at this time, including increasing rates of poverty, obesity, alcohol and opioid abuse, and smoking; poor health literacy; less access to health insurance and health care; reduced recommendations and usage of cancer screening services; and environmental risk factors, such as air and water pollution from strip mining and underground coal mining, help explain the seismic shift in cancer incidence and mortality between rural and urban America, according to Dr. Yao’s research.

The percentages in this map reflect the cancer mortality rates in rural Appalachian counties in these states compared to non-Appalachian urban areas nationwide between 1969 and 2011. All rural Appalachians in 12 states, except for Maryland, had higher mortality rates than their urban non-Appalachian counterparts living in the rest of the United States—170 deaths per 100,000 people. Source: Yao N, et al: J Rural Health. September 7, 2016 (early release online). Illustration by Peter and Maria Hoey © 2017

“There are many reasons causing the cancer disparities we see in rural Appalachia, including high smoking rates and few cessation programs, very high obesity rates and few exercise facilities, food deserts leading to poor nutrition, and environmental hazards in the water and air because of coal mining. We need to do something to change the trajectory of the situation in these communities. We want to see the cancer incidence and mortality rates go down, not up,” said Dr. Yao.

Impediments to Cancer Care

The Appalachian region of the United States covers a vast amount of territory—205,000 square miles—across 420 counties in 13 states, including all of West Virginia and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. It is home to approximately 24 million people, and about 42% of the

region is rural.4

Once wedded to thriving industries in coal mining and timber, textile, and steel manufacturing for economic survival, the loss of much of these businesses over the past half century has plunged many of these communities into chronic poverty—6 of the states in the Appalachian region are among the 10 poorest states in the nation5—and poor health. In addition to cancer, people living in Appalachia also experience high incidences of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,6 as well as lower life expectancy and higher rates of infant mortality,7 and there are few resources to circumvent the problem.

Although implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and expansion of Medicaid in some rural states have enabled more people living in these communities to gain access to health insurance and cancer screening services, which could potentially find cancers at earlier stages and improve survival odds, obstacles to obtaining high-quality, reliable cancer care remain.

Among the greatest impediments to care, whether it be for preventive screening or cancer treatment, is the small number of oncologists practicing in rural communities compared with the number practicing in metropolitan areas across the United States. According to ASCO’s State of Cancer Care in America 2016 report, the oncology workforce is so concentrated in big cities—fully 50% of all hematologists and oncologists practice in just eight states: California, New York, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Illinois—even though more than 11% of Americans live in rural cities, only 5.6% of oncologists provide service in these areas.8 Hospitals and health-care clinics in these regions are scarce as well and often out of reach for patients with limited means to travel long distances for care.

There are some patients with a strong belief that God will heal their cancer and a real fear of traditional medicine.— Melissa Dillmon, MD

Tweet this quote

“Transportation is a huge problem for these patients,” said Melissa Dillmon, MD, Chair of ASCO’s State Affiliate Council and a medical oncologist at Harbin Clinic in Rome, Georgia, which has provided health care for all patients of Northwest Georgia for over 100 years, regardless of insurance status. “Through a local nonprofit foundation, Cancer Navigators, we can provide some funding to defray the cost of travel, but when gas prices spiked a few years ago, it was a huge hindrance to getting patients to our clinic for treatment, especially for patients requiring daily rounds of radiotherapy for several weeks.”

“Patients are making treatment decisions based on what is feasible,” agreed Robert Croyle, PhD, Director of the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). “I have heard many stories about patients who are making critical treatment decisions based on the fact that they live in a rural area and can’t easily get to a hospital or clinic for care and opt instead for more aggressive treatment, such as mastectomy for breast cancer, rather than lumpectomy and radiation therapy, because there is no way they can get to some remote location 5 days a week for treatment.”

Patients are making treatment decisions based on what is feasible.— Robert Croyle, PhD

Tweet this quote

Geographic isolation and the long travel distances necessary to access cancer care may also be contributing to the higher cancer mortality rates in these regions. “People in these communities are diagnosed at later stages, and the result is the 3- to 5-year survival rates are worse than in other parts of the country,” said Dr. Yao. Even when patients can obtain cancer screening services, they are often reluctant to have follow-up care, possibly out of fear of a cancer diagnosis. “Between 15% and 20% of women who have an abnormal mammogram don’t go back for follow-up tests,” he explained.

Cancer Is Destiny

Existential factors come into play as well and may help to explain the disparities in cancer incidence and outcome. These factors include a long history of poverty and oppression; lower levels of educational attainment; a value system steeped in individualism, religion, modesty, community, and family solidarity; and a sense of fatalism of the inevitability of cancer and its consequences. In terms of education, 15% of rural Appalachians have not completed high school, and just 19% have a bachelor’s or higher degree compared with 33% of adults in urban areas.9

“Some patients with breast cancer come to us with more advanced disease, because even though they may have had a mammography screening showing a mass in their breast or felt a lump themselves, they are often reluctant to talk about it with family or see anyone,” said Dr. Dillmon. “There are some patients with a strong belief that God will heal their cancer and a real fear of traditional medicine. When they come to me, the cancer is very advanced, and they are going to have worse outcomes.”

Dr. Yao agreed. “When we talk about diagnosing cancer at a late stage, it often has to do with screening access and patients’ cultural beliefs. In rural Appalachia, some people are fatalistic and believe cancer is their destiny,” he said.

Serving the Underserved

Electra D. Paskett, PhD

For nearly 15 years, Electra D. Paskett, PhD, Marion N. Rowley Professor of Cancer Research and Director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control in the College of Medicine at The Ohio State University, has been working to alter that destiny and improve cancer rates in Appalachia through research and a hands-on approach to bringing oncology care to an underserved and mostly white rural population.

“This is a population that has a long history of being exploited by industrialists coming on their land promising jobs and better wages and being disappointed, so trust is an issue here, even for physicians trying to bring health care to these communities. Physicians who are not from these areas need to understand the culture of the community they are trying to serve to gain peoples’ trust,” said Dr. Paskett.

Dr. Paskett and her institution are part of the Appalachia Community Cancer Network (accnweb.com), an NCI-funded research initiative to reduce cancer disparities in the Appalachian region, with a specific focus on the cancers with the highest incidence rates, including cervical, colorectal, and lung, and an emphasis on prevention and early detection. The Appalachia Community Cancer Network’s primary activities include cancer and education awareness activities, community-based participatory research projects, and mentorship and training opportunities. The coalition includes a team of community partners and academic collaborators from five states: Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia.

John P. Little, MD, a pediatric otolaryngologist at East Tennessee Children’s Hospital in Knoxville, Tennessee, volunteered to participate in a Remote Area Medical mobile health clinic in Athens, Tennessee, on July 8, 2017. During his examination of a patient complaining of hearing loss, Dr. Little discovered a mass on the back of the man’s tongue that had spread to his neck. Dr. Little provided the patient with follow-up information for treatment. “[If the cancer had been diagnosed] at a much higher stage, it probably would not have been treatable,” said Dr. Little.

“The [Appalachia Community Cancer Network] works with local health clinics, physician practices, and community-based cancer coalitions to determine what the main cancer problems are in an area, such as high incidence or mortality rates, and raise awareness and conduct research projects on how to reduce cancer risk, for example, through smoking cessation programs, mammogram and colorectal screenings, Pap tests, and HPV vaccinations,” said Dr. Paskett.

Moreover, Dr. Paskett helps local coalitions write grants to finance cancer screening and patient navigator services and works with organizations to build community gardens to provide fresh produce in areas lacking farmers’ markets and access to healthy foods. “Our goal is to bring health-care services to local areas delivered in a manner that is culturally acceptable and helps patients get the appropriate care they need,” she explained.

Closing the Gaps in Health Care

Bringing appropriate health care to people in need is also the goal of Remote Area Medical, a global nonprofit organization launched in 1985 to deliver free medical care to remote countries around the world; then Remote Area Medical turned its attention to the unmet medical needs of people in the United States. Since then, Remote Area Medical has brought its high-quality mobile medical clinics to nearly 1 million adults and children across the country, providing basic dental, vision, and medical care through a voluntary network of more than 120,000 licensed medical practitioners, at a monetary value estimated at more than $114 million.

Although Remote Area Medical brings its mobile health-care services to more than a dozen communities across the country, the health clinic, or expedition as it is called, that draws the greatest number of patients is the one held each year in the small Appalachian town of Wise, Virginia. This past July, more than 2,000—mostly uninsured or underinsured—patients lined up in the parking lot of a county fairground that had been outfitted with makeshift dental, vision, and medical exam rooms for checkups and treatment. In most cases, patients leave these health clinics with decayed teeth extracted and cavities filled or their eyes examined and new prescription glasses in hand, bridging a gap left by the health-care system.

Jeff Eastman

“Sixty-five percent of the patients we treat are for dental problems, and about 30% are for vision issues, because most private health-care plans and Medicaid and Medicare don’t include benefits for these services,” said Jeff Eastman, Chief Executive Officer of Remote Area Medical. “Only about 5% of the people we see are for other medical reasons, because usually issues requiring immediate attention are dealt with at hospital emergency rooms.”

Still, over the years, said Mr. Eastman, hundreds of cancers have been found during oral and physical examinations and through mammography and Pap test screenings. Remote Area Medical then works with local area health-care organizations to provide follow-up oncology care for patients.

The dental care Remote Area Medical -provides may be doing more than fixing patients’ immediate oral problems; it could be preventing future systemic illness as well. A recent study found that postmenopausal women with a history of periodontal disease, including never smokers, are at a significant increased risk of developing cancer, especially lung, breast, esophageal, gallbladder, and melanoma skin cancers.10

The huge number of people flocking to Remote Area Medical health clinics each year, said Mr. Eastman, is a reflection of a costly health-care system that is out of reach for millions of Americans. “The people we see are your neighbors, your favorite waitress, or your kids’ teachers. These are working people. There are huge gaps in our health-care system. We will always be there to fill those gaps, but I would love for there to be no gaps in health care and for everyone to have access to the care they need. I would love to be out of the health-care business entirely and focus instead on our Remote Area Medical Rangers Youth Program for youths at risk,” said Mr. Eastman.

Improving Cancer Care in Rural Communities

The disparities in cancer incidence and outcome in rural parts of America are attracting increased attention at the NCI, which is holding its first national conference on cancer control in rural communities on May 30–31, 2018, to further inform NCI-funded research to improve cancer control in Appalachia. This conference includes efforts in cancer surveillance, colorectal cancer screening, and HPV vaccination.

Hundreds of patients received free dental services, including extractions, fillings, and cleanings from a Remote Area Medical health clinic held on February 4-5, 2017, in Knoxville, Tennessee. Studies show that maintaining good oral health reduces the risk for certain cancers, including oropharyngeal, lung, breast, and esophageal cancers.

“A major challenge is figuring out what the best strategy is for improving early cancer detection and treatment in communities where there is little or no primary care and rural hospitals are closing at a rapid pace, further exacerbating access to oncology care,” said Dr. Croyle. “We are currently in talks with health-care providers and researchers in these communities to see what NCI-supported programs can do to help address cancer disparities.”

Although telemedicine is often offered as a potential solution to mitigate limited access to health care across Appalachia, state and federal funding to build broadband infrastructure throughout these regions has not been adequate, and some counties are turning to academic institutions to provide virtual cancer care. For example, communities throughout Appalachia and Southwest Virginia are partnering with the University of Virginia Cancer Center’s Cancer Center Without Walls, a virtual hospital with an extensive broadband network, to gain access to screening, advanced cancer care, and clinical research. (See “Bringing Oncology Care to Rural Communities,” on page 92.)

ASCO is also actively engaged in finding new ways to reduce disparities in cancer care and outcomes; improve high-quality, high-value oncology care for patients; and advocate for public policy change. These public policy changes include Medicaid reform to increase office reimbursement, best practices for cancer prevention in rural regions, strategies to support research and the development of clinical cancer researchers in health disparities and build the supply of minority physicians, and solutions to expand the oncology workforce through greater utilization of advanced care practitioners and physician assistants.

Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD

“Ensuring access to cancer care for the underserved is a huge concern for ASCO,” said Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD, Immediate-Past Chair of ASCO’s Health Disparities Committee and Director of Hematologic Radiation Oncology and the Office of Cancer Health Equity at Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “A lot of the work ASCO is doing is relevant not just to racial and ethnic minority patients, but to other underserved communities as well, including patients in low socioeconomic regions, such as rural Appalachia. ASCO’s policy statement on Disparities in Cancer Care11 outlines the Society’s commitment to eliminate cancer health disparities and gives us the framework to improve care for underserved patients.”

However, cautioned Dr. Winkfield, completely eliminating inequities in cancer care for underserved patients will take time. “We’ve known that health disparities have existed in the black community for decades, and we have seen some improvement. We are making progress and need to make more. We have to make sure those patients who are already struggling in our health-care system do not get further behind by not having access to basic oncology care, including prevention and screening services and treatment.”

DISCLOSURE: Drs. Yao, Dillmon, Croyle, Paskett, Winkfield, and Mr. Eastman reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al: Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64:9-29, 2014.

2. Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, et al: Invasive cancer incidence, 2004–2013, and deaths, 2006–2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Surveillance Summaries, July 7, 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/ss/ss6614a1.htm?s_cid=ss6614a1_w. Accessed August 22, 2017.

3. Yao N, Alcalá HE, Anderson R, et al: Cancer disparities in rural Appalachia: Incidence, early detection, and survivorship. J Rural Health. September 7, 2016 (early release online).

4. Appalachian Regional Commission: The Appalachian Region. Available at https://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/TheAppalachianRegion.asp. Accessed August 22, 1017.

5. Baron S: Center for American Progress Action Fund. State of the States Report 2014: Local Momentum for National Change to Cut Poverty and Inequality. December 2014. Available at https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/StateofStates2014-report.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2017.

6. Borak J, Salipante-Zaidel C, Slade MD, et al: Mortality disparities in Appalachia: Reassessment of major risk factors. J Occup Environ Med 54:146-156, 2012.

7. Singh GK, Kogan MD, Slifkin RT: Widening disparities in infant mortality and live expectancy between Appalachia and the rest of the United States, 1990-2013. Health Aff (Millwood) 36:1423-1432, 2017.

8. ASCO: The State of Cancer Care in America 2016. A Message from ASCO’s President. Available at http://www.asco.org/research-progress/reports-studies/cancer-care-america-2016#/message-ascos-president. Accessed August 22, 2017.

9. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service: Rural Education. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education. Accessed August 22, 2017.

10. Nwizu NN, Marshall JR, Moysich K, et al: Periodontal disease and incident cancer risk among postmenopausal women: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:1255-1265, 2017.

11. Goss E, Lopez AM, Brown CL, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement: Disparities in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 27:2881-2885, 2009.