In 2019, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II appointed V. Craig Jordan, CMG, OBE, PhD, DSc, FMedSci, Companion of the Most Distinguished order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG), honoring his extraordinary scientific work in the development of selective estrogen receptor modulators, most notably tamoxifen. The CMG, one of the Crown’s most prestigious awards, is one of many bestowed on Dr. Jordan during his illustrious research career; however, more than awards, the millions of women whose lives were saved by tamoxifen serve as a living testament to his work.

Dr. Jordan’s journey from a precocious, chemistry--obsessed child to his current position at MD Anderson Cancer Center offers insights into the challenges of a life in cancer research. To that end, Dr. Jordan shared some of the salient moments in his life, with past boss, colleague, and trusted friend Steven Rosen, MD, Provost and Scientific Director at City of Hope.

Born in the Lone Star State

Dr. Jordan was born in New Braunfels, Texas, a city situated along the Balcones Fault, where the Texas Hill Country meets the rolling prairie land. “My English mother married a warrior from America who’d seen action at D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge. They were married at our family church in 1945 and went off to America; however, after 5 years, the marriage didn’t work, and she and I came back to Britain, where I was reared. My mother subsequently married Geoffrey Webster Jordan, one of her friends who adopted me as his son. My natural father led a mysterious life, should we say, in the Far East, the Philippines, and Thailand and had his headquarters in Silver Springs in Washington, which is apparently where the tricksters lived before they go out on their deeds,” he explained.

Dr. Jordan continued: “I had a formative period in my life at Moseley Hall Grammar School, where I grew to love chemistry and was fascinated with what different chemicals would do and make. With my mother’s permission, I converted my bedroom into a chemistry laboratory, but it was a real chemistry laboratory, not one of those kid’s kits, with the things I’d gotten from the pharmacy and liberated from school. This became my scientific workplace. There were multiple life-threatening moments when my experiments exploded or caught fire, and I had to throw things out the window. But my mother would always say, ‘at least we know where he is’ with the inference that, if he were doing this somewhere else, he’d probably be dead in pretty short time. So, the school also gave me opportunities to teach younger boys biochemistry; by then, I was already looking at university chemistry, first year courses in biochemistry, so I passed this on to younger boys, some of whom went straight off to medical school.”

A Headmaster’s Letter

According to Dr. Jordan, despite some lackluster grades, the Moseley Hall Grammar School headmaster saw a rising star in his young chemistry prodigy and wrote a superlative recommendation letter extolling Dr. Jordan as a very unusual young man. On the strength of the headmaster’s urging, Dr. Jordan was accepted to the highly regarded University of Leeds, which was not without some drama.

Dr. Jordan continued: “During my first year at Leeds, I was doing special studies pharmacy on a 4-year course, because I had never done physics before and had to play catch up. Frankly, I’d had no idea about physics, so I had a tough time, but I also questioned my decision to do pharmacy; by then, I was captivated about doing cancer research, because I saw this as the big universal problem, and it gave me the opportunity to truly make a difference. So, I went to the head of applications for coming into pharmacology, and he looked at my record. This was a heart-stopping moment because he basically said: ‘I don’t think you’re good enough.’ I restrained myself enough not to shout at him, but I did say in no uncertain terms that I would prove him wrong, nearly breaking the glass door when I slammed it on the way out,” said Dr. Jordan. I did all I said I would do in the examinations, but chose to remain in pharmacy.

Military Service

Dr. Jordan’s family has a rich history of military service. While doing his undergraduate work, his beloved grandfather, a distinguished veteran of two world wars, persuaded Dr. Jordan to enlist in the Leeds University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC). “As you know, the big threat at that time was the Cuban missile crisis. My grandfather had gently coerced me to go to the OTC by clever and cunning, so that’s what I decided to do. He was a force to be reckoned with. We would go to his house for Sunday brunch, and there were bayonets on the hearth, a pistol that had been hand-made for him during World War I, and target rifles. You knew where you stood with my grandfather, and his advice was always well thought out,” said Dr. Jordan.

However, when Dr. Jordan eagerly went to the military office to sign up for OTC, the colonel in charge held up the registration form he’d filled out and quite forcefully told Dr. Jordan that he was an American citizen born to an American father, and so he wasn’t qualified for service in the British armed forces. “I walked away dejected, but I took a chance and unbeknown to my parents, I called the family lawyer, who had me lawfully adopted by my English stepfather, which solved the issue of citizenship and got me enlisted into the OTC,” said Dr. Jordan.

“In my commissioning interview for the OTC, I said I wanted to attend all the nuclear, chemical, and biological warfare courses because I had a scholarship from the Medical Research Council and the scientific credentials to be the Army’s expert in this area. So, that’s what happened. During this training, I was noticed by the Deputy Chief Scientist for the Army; he said if I were to pass Top Security clearance, I’d immediately make captain’s rank, where I was to be the nuclear chemical and biological warfare expert in Germany, dealing with NATO should the Russians come over the border,” related Dr. -Jordan. “It was a terrific time in my life, and I was very proud to be able to serve as a British Army officer—Iwas a PhD student!”

An Influential Neighbor

Meanwhile, Dr. Jordan, had received a lucrative research grant and on the advice of his supervisor—who’d spotted his student’s unusual talent some 4 years before—began working on the structure activity of antiestrogens as part of his PhD program at Leeds University. As detailed in his new book, Tamoxifen Tales: Suggestions for Scientific Survival, the road to bringing tamoxifen to market was long and challenging, filled with twists and turns worthy of a novel.

The short version of that famous story began in the summer of 1967, when Dr. Jordan was working at ICI Pharmaceuticals with Steven Carter, MD, Head of the Anticancer Screening Program. “Across the hall, Arthur Walpole, PhD, Head of Reproduction Research, had recently published work on a new antiestrogen, ICI 46,474, as a murine contraceptive, in the hope it could be developed into a human contraceptive. Unfortunately, ICI 46,474 was not a contraceptive in women. However, within a few years, ICI Pharmaceuticals lost interest in the contraceptive pathway; however, ICI 46,474 did show a modicum of activity in early studies of metastatic breast cancer. During our discussions about using antiestrogens to treat breast cancer, Dr. Walpole, who had not only been my PhD examiner for my thesis on ‘failed contraceptives’ but had also become a trusted colleague, suggested we use the estrogen receptor as a target. That was really a jumping off point for me,” said Dr. Jordan.

With the support of Dr. Walpole and the Worcester Foundation, Dr. Jordan traveled to the United States and joined the Foundation’s laboratory in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, where he worked with laboratory models in breast cancer. In the interim, ICI Pharmaceuticals had acquired a company in the United States.

“I went to ICI’s Delaware office and was introduced to Ms. Lois Trench, ICI’s clinical drug monitor for ICI 46,474, which was reworked into tamoxifen. Lois arranged for me to study the interactions of tamoxifen with the estrogen receptor, and I literally threw myself into the work in the lab, writing papers and giving lectures. From the start, developing tamoxifen into an anticancer drug was a huge uphill battle, but seeing tamoxifen eventually become a life-saving mainstay in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer was very rewarding,” said Dr. Jordan.

A Return to His Roots

In 1974, Dr. Jordan would later return to his alma mater, Leeds University, as a lecturer in pharmacology, spending 5 fruitful years there before leaving for a year-long position at Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research at the University of Bern, Switzerland. In 1980, Dr. Jordan joined the University of Wisconsin–Madison as Assistant Professor, doing research on the long-term effects of tamoxifen and raloxifene on bone density and coronary systems. In contrast to a growing concern, Dr. Jordan’s research showed that postmenopausal women who took these drugs did not suffer from a lowering of bone density or an increase in blood cholesterol. In 1985, he gained a full professorship at Wisconsin, remaining there until 1993, when he was recruited to Northwestern University’s Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, by then Director Steven Rosen, MD, who Dr. Jordan would often characterize as “the best boss I ever had.”

Dr. Rosen noted that along with the multiple clinical trials Dr. Jordan initiated while at Northwestern, he was also a co-founder of the Lynn Sage Breast Cancer Symposium. “It was a terrific triumvirate between Bill Gradishar, who had miraculous outreach skills, Monica Morrow, who was a genius at putting programs together and fundraising, and me,” explained Dr. Jordan. “Steve pushed me to excel, and it really meant a lot.”

At this time, Dr. Jordan was just beginning to become famous for his work. “I remember getting a letter saying I’d received the Cameron Prize of the University of Edinburgh. Well, I’d never heard of the Cameron Prize, so I looked it up and lo and behold found that it’s awarded to the most famous people in the world who’ve made noted advances in human disease, people such as Louis Pasteur and Madame Curie. So, now they added Craig Jordan to that list. I went to Scotland and gave a lecture, and the Cameron Prize became my ace in the hole for my career moving forward.

A Royal Connection

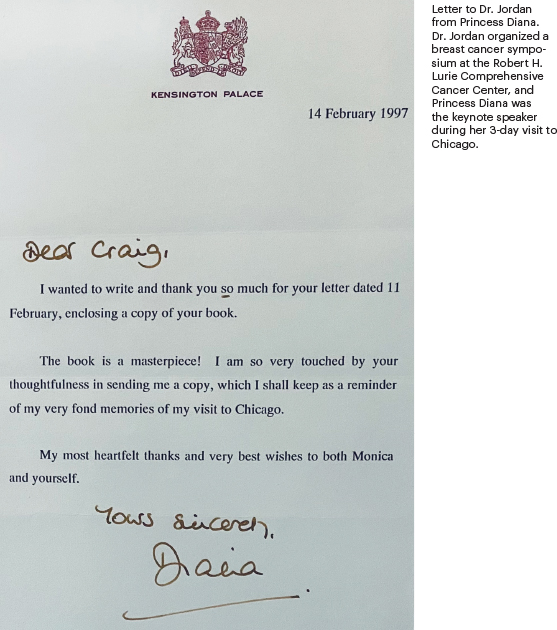

Dr. Rosen pointed to another historic highlight in Dr. Jordan’s tenure at Northwestern. Diana, the Princess of Wales, visited the Lurie Cancer Center of Northwestern University and helped to raise more than $1 million to support cancer research. During her visit, the Princess delivered the opening remarks at Northwestern’s inaugural Symposium on Breast Cancer, which was chaired by Dr. Rosen, who was Director of the Lurie Cancer Center, and organized by Dr. Jordan, then Director of the Lurie’s Breast Cancer Research Program.

Dr. Jordan remembered: “To this day, I have a clear picture in my mind of Princess Diana when she was our keynote speaker at the symposium. It was truly a terrific event, followed by a gala. After that connection, we became correspondents, and there were plans for her and her sons to return to Chicago in the future. She was dedicated to the mission of cancer research, and as tamoxifen was a British drug, and I was a Brit, well, there was good chemistry between us.”

“Just days after her Chicago visit, Diana wrote me a hand-signed letter on Kensington Palace stationery, which hangs in my office,” he continued. “By then, we’d gotten past the formalities, and it reads: ‘I will remember my trip to Chicago for a long time. As I said at the time, I wish you all the strength to press ahead with your vital work while we continue to provide you with all the support you will need in the years to come.’ And she had written it on Valentine’s Day, and I thought she was creating mystery and great sadness, too. As you can tell, I’m still moved by all of this.”

Dr. Jordan continued: “It was just about a year later, when I was at a breast cancer meeting; when I entered the room, the whole group of speakers and their spouses were gathered on the far side. Then my friend, Manfred Kaufmann approached me and very solemnly said: ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you, but your Princess is dead.’ It was overwhelming, to say the least.”

“Later, I was named the Diana, Princess of Wales, Professor of Cancer Research at Northwestern University, and Mrs. Lurie and the president of Northwestern did the honors of giving me my medal—the Diana, Princess of Wales Medal—which I’m permitted to wear on any occasion where I’m wearing academic dress. That’s the tradition. Whenever I receive honorary degrees, I wear the Diana, Princess of Wales Medal.”

A Career Change: Major Awards

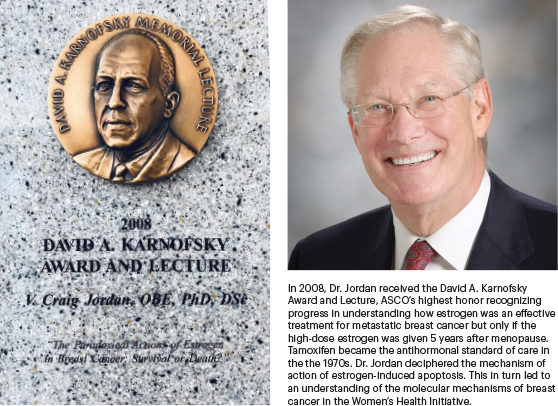

In 2005, after more than a decade at Northwestern, Dr. Jordan accepted an offer to become the inaugural Alfred G. Knudson Chair of Cancer Research at Fox Chase Cancer center in Philadelphia, where he continued to work on antiestrogens. As recognition for his past and continued scientific accomplishments, Dr. Jordan received the 2008 ASCO David A. Karnofsky Memorial Award, which is bestowed upon individuals who, through their clinical research, have changed the way oncologists think about the general practice of oncology. It is one of ASCO’s highest scientific honors.

“I remember getting a call out of the blue from the ASCO Awards Committee Chair, saying they wanted me to consider accepting the Karnofsky Award. Well, first off, no PhDs had ever won it before me, so that was a bit of an honor,” said Dr. Jordan.

Also in 2008, Dr. Jordan became one of five scholars from around the world to receive an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Society of Medicine at the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) in London. The award is one of the highest honors in British medicine.

When Dr. Rosen asked Dr. Jordan to sum up the message of his Karnofsky Award lecture, he replied: “The first Karnofsky lecture was given by another Englishman, Sir Alexander Haddow, in 1970. In his lecture, he noted he never thought there would be any ability to discriminate cancer from normal tissue, and consequently, we would never be able to have targeted therapies. So, my lecture was a response to Dr. Haddow’s disappointment. We now have a target. We understand the mechanisms of estrogen action and are taking it forward into clinical trials as a new modality to treat patients with advanced breast cancer who have failed to respond to antihormone therapy. It was a staggering 35-year story of how different ideas have changed medical practice around the world.” We discovered the new science of estrogen-induced apoptosis, following more than 5 years of estrogen deprivation.

An Offer He Couldn’t Refuse

In 2014, Dr. Jordan’s career arc took him to MD Anderson Cancer Center, where he was appointed Professor in Breast Medical Oncology and Molecular and Cellular Oncology, and awarded the Dallas/Fort Worth Living Legend Chair of Cancer Research. Here, he focused on the new biology of estrogen-induced cell death, with the goal of developing translational approaches for treating and preventing cancer. Asked about the circumstances that brought him to Houston, Dr. Jordan replied:

“I was at a cocktail party in San Diego for the AACR in 2013, which was being run by MD Anderson; I was basically asked if they wanted to buy my brain, how much would it cost? So, I just said a number, and without blinking an eye, they said ‘deal.’ And John Mendelson was there, and we shook hands on it, and it was a done deal. That’s just how things sometimes happen; despite the scorching heat in Houston, it was a great opportunity.”

“Stage IV renal cell carcinoma is dominant, but I refuse to die. It’s not in my nature.”— V. Craig Jordan, CMG, OBE, PhD, DSc, FMedSci

Tweet this quote

In 2018, Dr. Jordan was diagnosed with stage IV renal cell carcinoma, a subject that, although deeply personal, he speaks candidly about. In fact, he recounts his clinical struggles with the disease in several poignant vignettes in his book.

“The illness is dominant,” said Dr. Jordan, with his customary aplomb, “but I refuse to die. It’s not in my nature. There’s nobody I’ve received a letter from who doesn’t believe that Craig Jordan can do this, even if it’s less than a million percent chance, he’ll figure it out or do it. And so, I take immunotherapy and a targeted therapy. I’ve got a mass in my lungs. I currently have stable disease, which I am less than happy about because, if we’ve got it down to this point, why is it not possible to find the right paradigm to kill these tumors? I’ve had offers from people from Columbia University Hospital who are willing to cure Craig Jordan with some experimental techniques. So, I find myself in a state of flux, but I’m not scared of dying. I was the person most likely never to make age 30 with the stupid things I was doing in my youth, mainly with the Army.”

Throughout his life, Dr. Jordan has always been an active participant who values commitment and service, so despite his current challenges, he forges on, doing whatever he can to make a difference. “The training of the next generation of clinician-scientists is incredibly important to me,” he explained. “I have now one endowed lectureship at Oxford because they invited me to do that. Their view is that if we can get the most successful people in the world who have succeeded and inspire five people in the audience to succeed because of that, we will have done our job, and the scientific community will be better off for it. So, I’ve done that at their request and will be off to Britain shortly.”

A Stubborn Optimist

Dr. Jordan has two daughters, Helen, an executive in the music industry, and Alexandra, a lawyer who represents abused children. His first marriage ended in divorce, an experience he noted was difficult, especially for his children. He later married renowned breast cancer surgeon Monica Morrow, MD, who he referred to as his “rescuer.” Their professional challenges eventually took a toll, and the powerhouse oncology couple eventually parted amicably.

“The training of the next generation of clinician-scientists is incredibly important to me.”— V. Craig Jordan, CMG, OBE, PhD, DSc, FMedSci

Tweet this quote

“It was a sad day when we parted ways. Monica went to Memorial Sloan Kettering because that was very important to her, and she certainly made her mark, and it wasn’t easy. I’m very proud of her,” said Dr. Jordan.

As the discussion wrapped up, the indefatigable Dr. Jordan gave a brief itinerary of his upcoming lecture circuit and medical affairs: “Who would have dreamed all of this was possible for a kid who barely made it out of grade school? No matter what, I remain optimistic about the possibilities ahead in cancer research and plan to continue to do my part, whatever that may be, for as long as possible. It’s an exciting time to be around.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Jordan reported no conflicts of interest.

MORE INFORMATION

For more on the career accomplishments and professional journey of V. Craig Jordan, CMG, OBE, PhD, DSc, FMedSci, view an interview with him and Dr. Steve Rosen below.

Part 1: The Early Years

Part 2: Tamoxifen, Academia, and Accolades

Part 3: Tamoxifen Tales