The ASCO Post is pleased to continue this occasional special focus on the worldwide cancer burden. In this issue, we feature a close look at the cancer incidence and mortality rates in South Africa. The aim of this special feature is to highlight the global cancer burden for various countries of the world. For the convenience of the reader, each installment will focus on one country from one of the six regions of the world as defined by the World Health Organization (ie, Africa, the Americas, Southeast Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific). Each section will focus on the general aspects of the country followed by the current and predicted rates of incidence and cancer-related mortality. It is hoped that through these issues, we can increase awareness and shift public policy and funds toward proactively addressing this lethal disease on the global stage.

South Africa, situated at the southern tip of the African continent, has an estimated population of 57 million (Table 1).1 The country has a relatively young population, with 28.6% younger than age 15, and 8.5% of the population is aged 60 or older. Since 2006, the average life expectancy in South Africa has increased from 55.7 years to 68.5 years in women and from 52.3 years to 62.5 years in men. This improvement is largely attributed to the success of the antiretroviral program established to treat human immunodeficiency virus, which affects 13% of the population.2

Much of South Africa’s current social, political, and economic reality is shaped by the legacy of apartheid. This system of race-based discrimination systematically disenfranchised and economically oppressed the Black majority until it was overturned in 1994 with the advent of democracy.

South Africa is a country of diverse cultures, languages, and religions and ranks economically as one of only eight upper–middle-income countries in Africa.3 The economy is supported by strong mining, agricultural, and manufacturing sectors.4 Although it is a relatively wealthy country, inequality is a significant problem. South Africa continues to rank high on the list of countries in the world with inequity and has a Gini coefficient (a measure of statistical dispersion representing income or wealth inequality within a nation, ranging from 0 to 1) of over 0.6.5

South Africa spends 8.5% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care and has fewer than one doctor per thousand population.6 In 1994, the democratic government of South Africa inherited a fragmented health system with up to 14 different health ministries. The public health system has now been united into one National Department of Health, which serves 84% of the population, utilizing approximately half of the national health expenditure (4.2% of the GDP).7 South Africa also has a well-resourced private health sector, which serves 16% of the population. The economic inequality in the country is echoed in health care, with huge disparities in accessibility and quality of care between public and private sectors, as well as urban and rural areas.7

Cancer Profile in South Africa

Accurate collection of cancer incidence and mortality data is improving but remains a challenge in South Africa. A number of cancer surveillance systems are in place for collection of cancer data, but underreporting is a problem.

The largest cancer registry consists of a pathology-based cancer surveillance system and has been in place in South Africa since 1986, under the National Health Laboratory Service. This agency has provided collection, analyses, and reports of all cancer cases in South Africa diagnosed by cytology, histology, and bone marrow aspirate or trephine.

In 2003, the National Health Act of South Africa made cancer a reportable disease, but it was only in 2011 that a legalized entity, the National Cancer Registry (NCR), was created under the national Department of Health. Under this act, the NCR was charged with also establishing population-based registries. The first small, urban population-based registries were therefore created in the Ekurhuleni metropolitan municipality in Gauteng Province and at Frere hospital in the Eastern Cape province. These registries include data on all cancers, whether diagnosed clinically, radiologically, or pathologically.

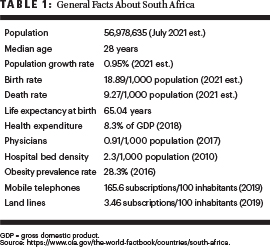

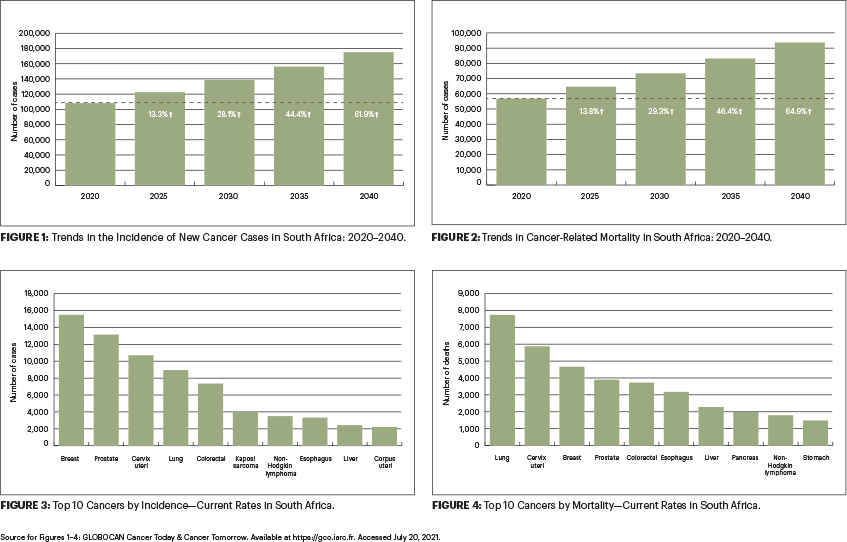

With the available data, it is estimated that in 2020, almost 110,000 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in South Africa, with more than 56,000 cancer-related deaths, representing a quarter of premature noncommunicable disease–related mortality. This significant cancer burden is predicted to increase in the coming decades, with the incidence of new cancer cases expected to rise to 138,000 and 175,000 in 2030 and 2040, respectively6 (Figure 1). Cancer-related mortality is predicted to rise to 73,000 and 94,000 during the same period (Figure 2).

The five most common cancers in South Africa, in order of incidence, are breast, prostate, cervical, lung, and colorectal (Figure 3). However, of these five cancers, the leading cause of cancer-related mortality is lung cancer (Figure 4). Among women, although breast cancer has at least a 25% higher incidence, cervical carcinoma is the leading cause of mortality.

Cancer Control Initiatives

South Africa has a number of cancer control initiatives in place to address the increasing cancer burden and also to work toward the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.8 At a national policy level, a National Cancer Strategic Framework (for 2017–2022) has been produced. This framework identifies lung, colorectal, cervical, prostate, and breast cancers as priorities. A specific focus on cancers of childhood and adolescence has also been identified.9

In addition to this overarching strategy framework, a number of other cancer control measures have been implemented. Legislation to curb tobacco use and smoking has been passed to decrease population-level exposure to the carcinogens in these products. Within the health services, there is a program for screening and early detection of cervical cancer. Childhood vaccinations against hepatitis B and human papillomavirus have been introduced in the past 2 decades, with an anticipated positive impact on the incidence of hepatocellular and cervical carcinomas in the future. Policymakers have also recognized the need to develop disease-specific national policy guidelines to align treatments in different parts of the country. In this regard, a breast cancer and cervical cancer control policy has been published by the National Department of Health.10

At a health services level, cancer care in South Africa is delivered within both the public and private health sectors. The oncology services in the public sector are mostly delivered through nine academic health complexes linked to the country’s nine universities.

Chemotherapy is offered at tertiary and some large secondary hospitals throughout the country, and standard-of-care drug regimens for the common cancers are accessible at most of these sites. Radiotherapy services are available at 11 oncology centers, with a total of 25 functioning units (as of 2021) within the public health sector. Additional centers are planned; however, human resource constraints and a lack of maintenance contracts continue to limit the reach of cancer care.

Multidisciplinary teams, including oncology, surgery, radiology, and pathology colleagues, are an integral part of the cancer treatment pathway in most public academic health centers. Palliative care is also increasingly being recognized and supported as a critical part of the cancer care pathway, with a growing number of trained palliative care specialists providing support and training to all clinicians involved in cancer management.

Barriers to Cancer Care

Despite these efforts and the existing oncology services, ready access to quality cancer care in South Africa remains extremely variable. In general, access depends on geographic location, socioeconomic status, and health insurance. Lack of population-based and primary health-care level awareness and education remains an issue, especially in rural populations. Geographic distances to cancer centers are also a problem for these populations.

There are still large discrepancies between the well-written and well-intentioned National Strategic Cancer Framework policy and the implementation of prevention, screening, and treatment strategies. Limitations are driven largely by cost of infrastructure and inadequate access to expensive medications, but also by lack of trained staff, with attrition to high-income countries and the more lucrative private sector. At a community level, simple issues, such as lack of transport, accommodation facilities, and family support during treatment, impact many patients, particularly rural patients and those from poorer urban settlements. These barriers, coupled with weak health referral pathways and inadequate access to diagnostic modalities, result in late-stage diagnosis for many patients with cancer and treatment abandonment for some.

To address these service issues and other disparities, the government plans to introduce a universal health-care coverage policy with a National Health Insurance (NHI) financing system, designed to pool funds and provide access to quality affordable health services for all South Africans based on their health needs, irrespective of socioeconomic status.11 The NHI plan is currently a bill before Parliament, and implementation is expected to be phased in over several years. From a cancer-specific viewpoint, both national and provincial departments of health have recognized the need for an additional budget for cancer care. However, this need competes with limited budgets required for other priority diseases, which now include COVID-19.

Further Efforts to Improve Cancer Care

Beyond the health system, many advocacy groups, including cancer survivors and health social movements, are active in highlighting the needs of patients with cancer and in cancer fundraising and awareness programs. In some centers, public nonprofit initiatives have been established to support cancer treatment services. These organizations also support the patient journey through the employment of community-based navigators. These practical interventions provide some immediate relief for patients struggling to access quality cancer services in the short term.

UNITED NATIONS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

- The UN’s sustainable development goals are a collection of 17 interlinked global goals designed to be a “blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.”

- They were set up in 2015 by the UN General Assembly and are intended to be achieved by the year 2030.

In the longer term, improving cancer care in South Africa will require work on many levels. At a broader level, South Africa needs strengthening of its health systems, human resource planning, and strategies to improve health equity. Specific to cancer services, community and primary care provider awareness of cancer symptoms and signs needs to be improved. This can be achieved through strengthening partnerships with patient advocacy groups, community-based health leadership, and nonprofit organizations. Finally, significant improvement in the care and outcomes for patients with cancer can be achieved through adequate resourcing and practical implementation of the cancer management plans outlined in the National Strategic Cancer Framework and related policy documents.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Cairncross, Dr. Parkes, and Ms. Craig reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Are is a board member with Global Laparoscopy Solutions; has received research funding from Pfizer; and has a patent with the University of -Nebraska Medical Center for a laparoscopy instrument.

REFERENCES

1. Central Intelligence Agency: The World Factbook—Africa: South Africa. Available at https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/south-africa. Accessed August 20, 2021.

2. Republic of South Africa, Department of Statistics: Stats SA. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

3. World Bank: World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed August 20, 2021.

4. Republic of South Africa, Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition: Trade, Investment and Infrastructure Development Handbook, 2010. Available at http://www.thedtic.gov.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

5. Ruch W, Leibbrandt M, David A, et al: Inequality Trends in South Africa: A Multidimensional Diagnostic of Inequality. Available at https://statssa.gov.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

6. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization: Cancer Today/Population Fact Sheets: South Africa, Globocan 2020. Available at https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/710-south-africa-fact-sheets.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2021.

7. Republic of South Africa, Department of Health: National Health Insurance for South Africa: Towards Universal Health Coverage. December 10, 2015, Version 40. Available at https://www.mm3admin.co.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

8. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development. Available at https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. Accessed August 20, 2021.

9. Republic of South Africa, Department of Health: National Cancer Strategic Framework for South Africa, 2017–2022. Available at https://www.health.gov.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

10. Republic of South Africa, Department of Health: Breast Cancer Control Policy and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Policy 2017. Available at http://www.health.gov.za/strategic-documents. Accessed August 20, 2021.

11. Republic of South Africa: National Health Insurance Bill, 2018. Available at https://www.gov.za. Accessed August 20, 2021.

Dr. Cairncross is Head of the Breast and Endocrine Surgery Unit and Associate Professor of Surgery at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. Dr. Parkes is Head of the Department of Radiation Oncology at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. Ms. Craig is Research Support Specialist at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. Dr. Are is the Jerald L & Carolynn J. Varner Professor of Surgical Oncology & Global Health; Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education; and Vice Chair of Education Department of Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.