Neal Shore, MD, FACS

The message still needs to get out that metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer should be treated with both androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) and either docetaxel or an androgen receptor pathway inhibitor. In spite of “overwhelming” support for ADT plus abiraterone/prednisone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, or docetaxel, recent surveys have shown that the majority of men with this disease still receive ADT alone, according to Neal Shore, MD, FACS.

“It’s no longer acceptable just to have a conversation with the patient about monotherapy testosterone suppression. One needs to discuss these other options with patients at the onset of therapy,” Dr. Shore said.

As part of the ASCO20 Virtual Education Program, Dr. Shore and Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH, sorted through the maze of treatment options for metastatic disease, first in the hormone-sensitive setting, then for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.1 Dr. Shore, Medical Director of the Carolina Urologic

Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH

Research Center, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, discussed androgen receptor–directed intensification for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Dr. Morgans, Associate Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed treatment of prostate cancer that has become resistant to hormonal manipulation.

Choosing an Androgen Receptor–Directed Agent

In the metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer setting, disease can be de novo (ie, newly diagnosed) or can recur after prostatectomy or radiation. Patient age and conditioning can vary from young and healthy to old and frail. Tumor burden on imaging can be minimal or widespread. Treatment history is also varied.

Against this multitude of factors, clinicians must choose among the following main treatment options: ADT alone or with docetaxel, abiraterone acetate and prednisone, enzalutamide, or apalutamide—all with level 1 evidence supporting their use. They must also grapple with whether to treat the primary tumor and how to approach oligometastatic disease.

Dr. Shore focused on intensification of ADT with an androgen receptor–pathway inhibitor, noting that the benefit is clear from hazard ratios (HRs) achieved in these pivotal trials:

- LATITUDE (ADT plus abiraterone): HR = 0.47 (P < .001) for radiographic progression-free survival and 0.62 (P < .001) for overall survival2

- TITAN (ADT plus apalutamide): HR = 0.67 for overall survival (P = .005)3

- ARCHES (ADT plus enzalutamide): HR = 0.39 (P < .001) for radiographic progression-free survival4

- ENZAMET (ADT plus enzalutamide): HR = 0.67 (P = .002) for overall survival.5

Although the studies differed in populations and in definitions of such factors as high-volume disease, their collective message is clear, he said: the addition of an androgen receptor–pathway inhibitor improves outcomes over ADT alone.

Side Effects to Consider

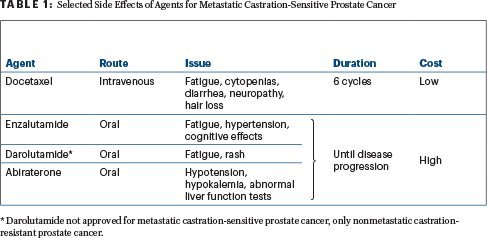

Given their largely similar benefit, the androgen receptor–pathway inhibitors can be differentiated somewhat based on side-effect profiles, which can be important considerations for patients (Table 1). Possible cardio-oncology and neuro-oncology issues may especially affect treatment selection and management considerations. “These issues should be top of mind for clinicians,” he said.

Regarding the question of treating the primary tumor in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, STAMPEDE found that in patients with low-volume disease, the addition of radiation to ADT plus abiraterone or docetaxel resulted in a survival benefit, but in patients with high-volume disease, radiation conveyed no additional benefit.6 “This is an important finding for consideration with regard to local therapy,” he commented.

Oligometastatic Disease: An Ongoing Question

Still to be settled are questions about managing oligometastatic disease: Should treatment be designed according to the different presentations—de novo or synchronous vs oligorecurrent or metachronous vs oligoprogressive disease? The number and site of lesions, prior treatment of the primary, accuracy of imaging, and treatment goal are other factors to consider.

Putting It All Together

Overall, at this point, the choice of add-on therapy for ADT can be based on clinical benefit (eg, overall and cancer-specific survival, quality of life); disease-specific characteristics (eg, tumor volume, genomic alterations, risk of disease progression); patient-specific factors (eg, age, comorbidities, laboratory values); and drug-specific factors (eg, adverse events, drug-drug interactions, accessibility, cost, route of administration, treatment duration), Dr. Shore said. He referred listeners to a table in the 2020 ASCO Educational Book’s article on treatment of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, which summarizes key data for the main treatment options.7

Meanwhile, advances are being made in combination therapy, with results pending on clinical trials evaluating triplets and novel agents: ADT plus docetaxel and darolutamide, ADT plus docetaxel and abiraterone, ADT plus enzalutamide and pembrolizumab, ADT plus abiraterone and capivasertib. “There are ongoing randomized trials that should give answers to many questions and, hopefully, expand our treatment armamentarium,” he said.

Treatment Considerations in Castration-Resistant Disease

After progression to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, the next treatment should account for treatment given in the prior setting. “As we choose where to go next, it’s critical for us to understand where our patients have been. At this point, we are fortunate to have multiple options that we can continue into the second line, third line, and beyond,” said Dr. Morgans.

Selection of an agent with a new mechanism of action is wise, she said. This is probably more relevant to androgen receptor–targeted agents than to chemotherapy, since evidence suggests cabazitaxel can be effective after prior docetaxel, she noted. In sequencing, the use of agents with novel mechanisms of action will address the resistance that develops with androgen receptor–targeting agents.

In addition, visceral vs bone-only metastasis, symptomatic vs asymptomatic state, and fitness for chemotherapy are factors to consider for anindividual patient. Histology also matters: is there a small cell/neuroendocrine differentiation that would make the patient a candidate for platinum-based chemotherapy vs another option? Are there targetable DNA repair defect mutations that will sensitize him to poly (ATP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors? Is there microsatellite instability that would predict for response to checkpoint inhibition?

Accessibility to treatments in one’s own practice location is another factor. And importantly, she advised, “Always think about whether there are clinical trial options that may be a good fit.”

Lack of Benefit for Sequencing Agents

“A general principle of my practice is that sequencing of androgen receptor–targeted agents, even if separated by docetaxel, radium-223, or sipuleucel-T, will be poorly effective for most patients, most of the time,” Dr. Morgans said.

The lack of benefit for sequential androgen receptor–targeted drugs was fairly “pronounced” in the CARD study, she noted, where median progression-free survival for this approach was only 2.7 months; patients fared better with cabazitaxel after disease progression on docetaxel and an androgen receptor–targeted agent.8 Similarly, in the phase III PROfound trial, patients with DNA repair defects achieved longer progression-free survival with olaparib than with a second androgen receptor–targeted agent.9 The 3.5-month progression-free survival with sequential androgen receptor–targeted agents was similar to the outcomes in CARD. The findings of the two studies were comparable, despite differences in duration of response to the initial androgen receptor–targeted drug, she said.

“We have seen in multiple trials a pretty consistent message: This should not be our standard of care unless there is truly a compelling reason to try that second agent for a particular patient—and those reasons are relatively few and far between,” according to Dr. Morgans.

Interesting Findings in Specific Subsets

In the United States, sipuleucel-T immunotherapy is an option for patients with no visceral metastases and relatively asymptomatic disease. Data from the PROCEED registry, which monitors patients in “real-world” practice, showed that Black men derived a significantly longer median overall survival (35.3 months) than White men (25.8 months; HR = 0.702; P < .001).10 Lower baseline prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was also associated with better survival than PSAs over the median. “These findings give an interesting take on this therapy and are important to think about,” she said.

Also intriguing were findings for radium-223 from the European early-access program; the population included both symptomatic and asymptomatic men with bone-only metastases.11 Although the drug’s indication is for symptomatic bone-only metastases, in the registry the overall survival was actually better in asymptomatic men, perhaps because they had more drug exposure (HR = 0.486).

“We may want to use medications that are effective in this population (like radium-223) in a setting where patients can receive more cycles of therapy,” she suggested.

Targeted Approaches in Specific Populations

For patients with DNA repair defects, the PARP inhibitors olaparib and rucaparib may be options. Olaparib reduced the risk of radiographic disease progression by 51% vs physician’s choice of therapy (P < .0001) in the PROfound trial.9 Olaparib is approved for men with any homologous recombination–repair mutations after androgen receptor–targeted therapy, before or after a taxane. Rucaparib is approved for men with BRCA1/2 mutations after an androgen receptor–targeted therapy and a taxane.

For patients who have tumors with microsatellite instability–high status, which is true for 2% to 3% of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers, pembrolizumab can produce pronounced radiographic responses, she said.

Importance of Shared Decision-Making

“There are often no specific medical indications to tell us which direction to go in terms of treatment. In that kind of setting, patient preferences are critical and should always guide our treatment choices,” Dr. Morgans emphasized.

Patient preferences relate to obligations at home and at work, past experiences of the patient or people he has known, fears about particular approaches, concerns about insurance restrictions, and other factors. These feelings are important but can be overlooked, she said, “unless you ask the patient.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Shore has served as a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Dendreon, Ferring, Genentech/Roche, Janssen, Medivation/Astellas, Merck, Myovant Sciences, Pfizer, and Tolmar; and has participated in speakers bureaus for Bayer, Dendreon, and Janssen. Dr. Morgans has received honoraria from, or served as an advisor or consultant to, Astellas Colombia, Astellas Scientific and Medical Affairs, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech, Janssen, Sanofi, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Myovant Sciences, and Sanofi; has received travel funding from Sanofi; and has received research funding from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech, and Seattle Genetics/Astellas.

REFERENCES

1. Shore ND: Sorting through the maze of treatment options for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. ASCO20 Virtual Education Program.

2. Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al: Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 377:352-360, 2017.

3. Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al: Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 381:13-24, 2019.

4. Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, et al: ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 37:2974-2986, 2019.

5. Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al: Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 381:121-131, 2019.

6. Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, et al: Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 392:2353-2366, 2018.

7. Schulte B, Morgans AK, Shore ND, et al: Sorting through the maze of treatment options for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. ASCO Educational Book 40:198-207, 2020.

8. De Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, et al: Cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2506-2518, 2019.

9. Hussain M, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al: PROfound: Phase III study of olaparib versus enzalutamide or abiraterone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with homologous recombination repair gene alterations. ESMO 2019 Congress. Abstract LBA12_PR. Presented September 30, 2019.

10. Sartor O, Armstrong AJ, Ahaghotu C, et al: Survival of African-American and Caucasian men after sipuleucel-T immunotherapy: Outcomes from the PROCEED registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 23:517-526, 2020.

11. Heidenreich A, Gillessen S, Heinrich, et al: Radium-223 in asymptomatic patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases treated in an international early access program. BMC Cancer 19:12, 2019.