Just 4 months after President Barack Obama’s announcement in December 2014 that there would be an easing of the trade embargo between the United States and Cuba, a deal was struck between Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, and the Center for Molecular Immunology (CIM) in Havana, Cuba, to test a immunotherapy vaccine for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the United States.

The vaccine, known as CimaVax EGF, was developed by CIM and has been approved for the treatment of late-stage NSCLC in Cuba and Peru. Although not a cure, CimaVax has been shown in phase III clinical trials in stage III and IV NSCLC to extend survival between 4 and 6 months, curtail symptoms like coughing and breathlessness, and improve overall quality of life. The vaccine is now being tested in Japan and several European countries.

The agreement between Roswell Park Cancer Institute and CMI to develop CimaVax in the United States was made during the New York State Trade Mission to Cuba in April 2015, but a partnership between the two institutions has been in place since 2011, when investigators from Roswell Park and CIM began exchanging academic and preclinical research information. Soon after, Roswell Park received a licensing agreement from the Government Center for Quality Control of Medicines, the Cuban regulatory authority, to test CimaVax in the laboratory.

Long-Term Objectives

If the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves Roswell Park’s investigational new drug application, which is expected by early 2016, the cancer center will launch a phase I study of the vaccine to investigate toxicities, followed by a phase I study of the drug to test efficacy in patients with early-stage NSCLC.

“Our hope for this vaccine longer term, beyond those early studies, is to see how effective it is in patients that don’t have as much tumor burden as stage III or IV lung cancer patients,” said Candace S. Johnson, PhD, President and CEO, Wallace Family Chair in Translational Research, and Professor of Oncology at Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

“After we finish our toxicity phase I approach, which won’t take long to complete since the drug has already been tested in early clinical studies in Cuba, we would like to study the vaccine in patients presenting with a single malignant nodule, because even though those patients are good candidates for surgery, they are at high risk for disease recurrence. We want to see if we can elicit a more long-term response in early-stage patients.” If the studies prove successful in the treatment of lung cancer, according to Dr. Johnson, Roswell Park proposes to test CimaVax in other cancer types with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, including prostate, breast, and colon cancers, and for the prevention of epithelial cancers.

CimaVax EGF works by depriving tumors of epidermal growth factor by making the protein immunogenic and inducing an immune response that reduces the amount of circulating EGF protein in patients, stunting tumor progression. Targeting EGF protein, said Dr. Johnson, provides a totally different mechanism for prohibiting cancer cell growth than the tyrosine kinase inhibitors approved by the FDA in the treatment of advanced-stage NSCLC, including erlotinib, gefitinib (Iressa), and afatinib (Gilotrif), and so may produce fewer side effects.

“Because CimaVax immunizes patients to make antibodies against the EGF protein, it is inherently probably not going to have the side effects of a drug like erlotinib, where you are trying to achieve some inhibition of receptor activity,” said Dr. Johnson. “Inducing an immune response with CimaVax could have side effects like fever and chills, but actually the reports from the Cuban scientists show very little toxicity from the vaccine. We will have to sort this all out ourselves once we begin clinical studies.”

In addition to CimaVax, Cuba’s CIM has developed a second vaccine for NSCLC called racotumomab (Vaxira) and the monoclonal antibody nimotuzumab for the treatment of glioblastoma, which is being studied in both adult and pediatric patients.

Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Innovative oncology drugs are not the only Cuban-made medications attracting attention outside their shores. Heberprot-P, a novel therapy for advanced diabetic foot ulcers, was developed 9 years ago by the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology in Havana. The drug, which contains recombinant human epidermal growth factor, has been shown in clinical studies to accelerate healing of deep and complex ulcers and reduce diabetes-related amputations,1 according to some reports by between 75% and 80%. Although not available for clinical testing in the United States because of the trade embargo, Heberprot-P is being used in 26 other countries and is reported to have treated as many as 165,000 patients with diabetic foot ulcers.2

Coming in From the Cold

Scientific collaborations between the United States and Cuba are not new and date as far back as the mid-19th century, when Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and naturalist Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian’s Assistant Secretary, began exchanging letters, documents, and scientific literature with Felipe Poey, a professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Havana and the founder of Havana’s Museum of Natural History. Other scientific partnerships followed, most notably between American physician Jesse Lazear, MD, and Cuban scientist Carlos Finlay, MD, whose groundbreaking investigations in 1900 proved that mosquitoes carry yellow fever.

By 1961, however, diplomatic ties between the two countries were severed as the Cold War heated up, and a full economic embargo, which included prohibitions on the importation of equipment and supplies and stringent travel restrictions, was imposed by the United States on Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis the following year cemented U.S. economic and diplomatic isolation of Cuba for the next 53 years.

Despite the embargo’s crippling economic sanctions on Cuba, which has stymied the import of computer technology and modern medical research equipment—CMI has only one flow cytometer to study cancer cells, according to Dr. Johnson—the country has maintained a thriving scientific community. This community includes 6,000 scientists3 and a universal health-care system that has reduced the infant mortality rate to 4.7 per 1,000 live births in 2014, compared with 6.17 in the United States,4 and at a fraction of the cost. According to the World Bank, in 2013, expenditure on health care per capita in the United States was $9,146, compared with $603 in Cuba.5

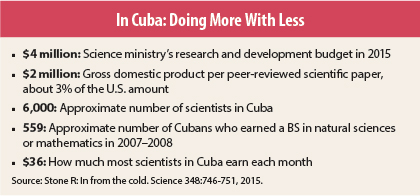

“The Cubans have had to do more with less [see sidebar] and have had to use their innovative minds to create solutions to achieve what they’ve wanted to,” said Dr. Johnson. “They may not have the fancy equipment that we do, but their infant mortality rate is better than ours, and if you look at the mean survival rate of their citizens, 79 years, it’s not different from ours.”

Forging New Scientific Collaborations

Although the economic embargo has stifled scientific collaborations between the United States and Cuba, it has not completely eliminated them, and U.S. scientists have been traveling to Cuba in recent years, financing the trips with private or foundation funds. “I have had the opportunity to make scientific visits to Cuba, and it is obvious that while our governments have had difficulty communicating, we have not,” said Peter Agre, MD, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor and Director of the Johns Hopkins Medical Research Institute, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Bloomberg School of Public Health; Past President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; and a co-recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“While Cuba is desperately poor because of the embargo, the scientists there are doing remarkable work and have had some formidable success in cancer and other research, and we need to know about it,” continued Dr. Agre. “It is in our best interest to have the opportunity to meet our counterparts face-to-face, not just in occasional e-mails, and share our knowledge. Cancer knows no socioeconomic boundaries, and the advances that are likely to occur from the collaboration between the scientists at Roswell Park Cancer Institute and CMI could help all Americans and people in other countries as well. I have no doubt that the collaboration will lead to productive developments in research and maybe breakthroughs, which will translate into improved clinical care for patients with lung cancer and other diseases.”

A New Era in Détente

Since the announcement in December 2014 of a policy shift toward Cuba, the United States and Cuba have reopened their embassies in Havana and Washington, DC, reestablishing diplomatic ties between the two countries. In addition, Cuba was removed from the list of nations that sponsor terrorism, signaling a new era in détente. However, until the American trade embargo is lifted, which will take an act of Congress and is unlikely to happen soon, the ability to fully engage in collaborative scientific research between the two countries will remain limited and opportunities for progress slowed.

“After more than half a century without diplomatic relations, a variety of issues will need to be resolved between the two countries, including visa obstacles and overcoming obstructed sharing of data, resources, and knowledge, and many would argue against a warmer relationship until certain steps are taken first. But science deserves a chance to move forward now,” said Sergio Jorge Pastrana, Foreign Secretary and Executive Director of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba in Havana.

“Joint research in almost any field can only work for the best aims and needs of both countries and should be favored without any prerequisites. The evidence strongly suggests that joint scientific research between Cuba and the United States can provide opportunities for progress and capacity building in both countries and elsewhere,” he added.

Mr. Pastrana continued: “There is a lot of misunderstanding between our two countries because of the policy that has been in place for more than 50 years. I only wish to assure all Americans that if they come to Cuba, they will find it is very different from the idea that has been created by misunderstanding for too long.” ■

Disclosure: Drs. Agre and Pastrana reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Berlanga J, Fernández JI, López, E, et al: Heberprot-P: A novel product for treating advanced diabetic foot ulcer. MEDICC Rev 15:11-15, 2013.

2. Reed G: Renewed U.S.-Cuba relations: Saving American lives and limbs? Huffington Post, posted January 24, 2015; updated March 26, 2015. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/gail-reed/renewed-uscuba-relations-_b_6537518.html. Accessed August 18, 2015.

3. Stone R: In from the cold. Science 348:746-751, 2015.

4. Central Intelligence Agency: The World Factbook. Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2091rank.html. Accessed August 18, 2015.

5. The World Bank: Health expenditure per capita (current US$). Available at data.worldbank.org/indicator/sh.xpd.pcap. Accessed August 18, 2015.