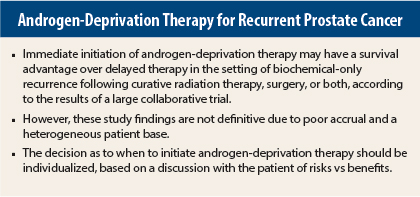

There is no consensus as to whether it is better to treat immediately or to delay androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with a rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (“biochemical relapse”) after curative therapy for prostate cancer. A phase III study, selected for the Best of ASCO® 2015, found that immediate androgen-deprivation therapy improved overall survival and time to clinical disease progression, but the results were not definitive.

This trial has several issues that make it difficult to walk away with a firm conclusion, according to Terence W. Friedlander, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, who reviewed this trial and its implications at the Best of ASCO 2015.

Study Details

About 20% to 50% of patients will relapse following definitive therapy for prostate cancer. The Timing of Androgen-Deprivation Therapy in Prostate Cancer Patients With a Rising PSA (TOAD) study sought to address the optimal timing of androgen-deprivation therapy in this setting. Men were eligible for the trial if they had a PSA doubling time of less than 12 months following curative therapy or metastasis or symptoms.

Only one-third of the planned accrual occurred, with 293 patients enrolled from September 2004 to July 2012. Median follow-up was 5 years. Most patients had slowly progressing disease, and about two-thirds of each arm went on intermittent therapy.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive immediate intervention with androgen-deprivation therapy (arm B) or delayed therapy (arm A). About one-third of patients in arm A initiated androgen-deprivation therapy within 2 years, whereas 49% started therapy later than 4 years on trial or had not yet begun therapy.

The mean age was about 70 years at trial initiation. About two-thirds of patients had curative radiation therapy, and about one-third underwent surgery plus radiation as curative therapy. The relapse-free interval was less than 10 months in about one-third of patients and 10 months or longer in two-thirds.

Survival Data and Toxicity

At 5 years, overall survival was about 10% higher if androgen-deprivation therapy was started immediately: 86% vs 76%, respectively; 6-year overall survival was 81% vs 65.4%, respectively (P = .05). Nonsignificant reductions were also observed in prostate cancer–specific deaths and deaths due to all causes.

Overall, 46 deaths were reported, including 30 deaths in the delayed-therapy arm and 16 deaths in the immediate-therapy arm. “There were only 18 prostate cancer deaths in this study—6 of these deaths were in the immediate [androgen-deprivation therapy] arm and 10 were in the delayed arm. It is difficult to interpret these data to know if this is a real difference,” Dr. Friedlander commented.

Progression-free survival (both distant and local) was improved with immediate therapy (P = .001) compared with delayed therapy. However, time to castration resistance did not differ between the two study arms.

A subgroup analysis suggested that intermittent androgen-deprivation therapy might be superior to continuous androgen-deprivation therapy. However, due to poor accrual, the study was underpowered to detect a difference in this and other secondary endpoints.

Adverse events related to androgen-deprivation therapy were more common in the immediate-therapy arm than in the delayed-therapy arm: 80% vs 50%.

‘Not Practice-Changing’

“This was a challenging trial to conduct, and accrual was disappointing. It appears that overall survival may be improved by immediate vs delayed initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy, but the benefits are likely to be modest and have to be balanced with the considerable side effects of hormonal treatment,” stated Dr. Friedlander.

“This study is not practice-changing. When faced with a patient with a rising PSA following curative therapy, the physician should discuss therapeutic options incorporating the risks of treatment,” he said. The way forward will depend on finding better ways to identify which patients need androgen-deprivation therapy upfront and which ones can safely delay it. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Friedlander reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Duchesne et al: 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 5007. Presented May 29, 2015.