The treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is rapidly evolving as molecular targets are being refined and targeted drugs are designed to combat acquired resistance. In his State of the Art Lecture at the 14th International Lung Cancer Congress, Dr. Bunn, Professor of Medicine and the James Dudley Chair in Cancer Research at the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora, Executive Director of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), and former ASCO President, described current treatment of NSCLC and the promise posed by future approaches.

Treatment Recommendations

Summarizing the current treatment algorithm, Dr. Bunn reminded oncologists that clinical features, histology, and molecular features must all be considered to select initial therapy. The need to perform molecular testing on essentially all patients is recommended in guidelines from ASCO, the College of American Pathologists (CAP)/IASLC/Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). While platinum doublets are generally restricted to patients with performance status 0 to 2, oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be considered for performance status 3, and thus, such patients should also undergo molecular testing.

Histology is also a key determinant of therapy, as pemetrexed (Alimta) is indicated only for patients with nonsquamous histology, bevacizumab (Avastin) is also not indicated for squamous histology, and patients lacking the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or ALK fusion should be treated with a platinum doublet, as they respond better to, and may live longer on, chemotherapy than an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

“This all means that performance status, histology, and molecular features should be determined before you embark on treatment,” said Dr. Bunn. “Don’t start patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line therapy in the absence of a driver abnormality. If you can’t assess the mutation status or confirm EGFR wild-type, give chemotherapy first.”

For patients who show slow disease progression with changes in symptoms on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, the unanswered question is whether to continue this drug or switch to chemotherapy. “In our clinic, we generally continue the tyrosine kinase inhibitor,” he said. A randomized clinical trial is currently evaluating this issue.

If a patient on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor develops a single metastatic lesion that can be resected or irradiated, the patient can continue on the same drug, which can add another 6 to 10 months without progression. “Unfortunately, these drugs don’t cause complete remissions and don’t cure patients,” he acknowledged.

Targeting EGFR and ALK

It is now well accepted that EGFR is not the only driver oncogene in NSCLC. Targeting of the ALK rearrangement with crizotinib (Xalkori) has made a substantial difference for the small subset of patients who have this abnormality.

Accelerated approval for crizotinib required a follow-up randomized trial, PROFILE 1007, which showed more than a doubling in progression-free survival with crizotinib, compared to docetaxel or pemetrexed, in the second-line setting. The results of the first-line randomized trial comparing crizotinib to a platinum doublet are still awaited.

Development of Resistance

Half of EGFR-mutated tumors in patients treated with gefitinib (Iressa) or erlotinib (Tarceva) subsequently develop a secondary gatekeeper mutation, leading to acquired resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Pharmaceutical companies are now investing in second- and third-generation agents that will bind to the secondary mutated pocket.

The first-generation agents bind to activating EGFR mutations and the wild-type receptor alike but not to the T790M mutation. The second-generation drugs bind to other members of the HER family, and to some degree to T790M, with the best outcomes observed with the combination of afatinib (Gilotrif) plus cetuximab (Erbitux). The third-generation agents offer irreversible binding of activating EGFR and T790M mutations but not the wild-type receptor, which could mean far less skin toxicity and diarrhea. Several such compounds are in development, Dr. Bunn reported.

For crizotinib, the mechanisms of resistance are similar, including the possible emergence of a second oncogenic driver in ALK-positive patients or a separate oncogenic driver in ALK-negative patients. Several second-generation ALK inhibitors in development are quite potent for the ALK gatekeeper mutations, producing extremely high response rates (about 75%).

“Clearly, we will be seeing randomized controlled trials of these in the second-line setting after crizotinib failure and likely in the first-line setting compared to chemotherapy,” Dr. Bunn predicted.

He added that ALK-positive patients are particularly sensitive to pemetrexed. Therefore, treatment with this agent after progression on crizotinib might be effective. The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) will conduct a randomized trial (SWOG-1300) to evaluate pemetrexed alone or with continued crizotinib after progression.

More Oncogenes, Targets

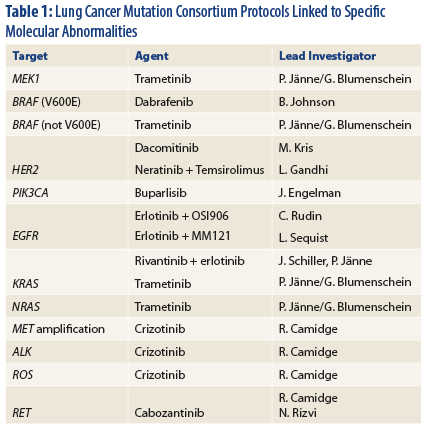

That said, two oncogenes do not describe the whole NSCLC tumor spectrum. The Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium is investigating more than a dozen molecular lesions and their biomarkers (Table 1) and have designed clinical trials for each, said Dr. Bunn.

Nearly two-thirds of patients with adenocarcinomas have at least one driver mutation for which a drug is available. Median survival for patients who have a molecular driver and receive such targeted therapy in the Consortium studies is about 3.5 years.1

Immunotherapy also presents a promising new avenue of attack in NSCLC. In a phase I trial in 122 heavily pretreated NSCLC patients, the anti–programmed death (PD)-1 antibody BMS-936558, a coinhibitory receptor expressed by activated T cells, showed clinical activity at all dose levels.2 The overall response rate was 18%, and the progression-free survival rate at 24 weeks was 26%. A trend for increased disease control was observed in tumors with squamous histology.

At least two anti–PD-1 agents and two anti–PD-L1 agents (ie, blocking the ligand) are in development. “We don’t know if one is better than the other, or if one target is better, or if we can combine them, or if there is a biomarker, but we do know that responses are associated with all these drugs, and patients have had prolonged progression-free survival on them,” Dr. Bunn noted. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Bunn is a consultant for Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck, Merck Serono, Merrimack, Myriad, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, and Synta.

References

1. Kris MG, Oxnard GR, Johnson BE, et al. 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 8085. Presented June 1, 2013.

2. Brahmer JR, Horn L, Antonia S, et al. 2012 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 7509. Presented June 2, 2012.