Some oncology drugs are in such short supply that the situation is now critical, with almost 200 drugs affected—triple that of 2003. This was the background described by speakers at a July 2011 congressional briefing sponsored by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), ASCO, and other cancer organizations.

In the past 2 years, according to a survey conducted by ACCC, Community Oncology Alliance, and Association of Oncology Social Work, almost every facility (94.4%) that provides cancer care experienced a drug shortage, said Matthew Farber, MA, ACCC Director of Provider Economics and Public Policy. Further, 84% of institutions said they had to temporarily suspend or modify a treatment regimen as a result of the shortage, and 63% spent more time and effort procuring drugs in 2010 than during the previous year.

In the past 2 years, according to a survey conducted by ACCC, Community Oncology Alliance, and Association of Oncology Social Work, almost every facility (94.4%) that provides cancer care experienced a drug shortage, said Matthew Farber, MA, ACCC Director of Provider Economics and Public Policy. Further, 84% of institutions said they had to temporarily suspend or modify a treatment regimen as a result of the shortage, and 63% spent more time and effort procuring drugs in 2010 than during the previous year.

All providers have been affected, said Ali McBride, PharmD, Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, although it isn’t as bad in large cancer centers as in smaller community ones. Moreover, every type of cancer has been affected, and many of the difficult-to-obtain drugs are the standard of care.

Problem Is Increasing

ASCO President Michael P. Link, MD, Lydia J. Lee Professor of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, said that the shortage is not improving and noted that in addition to antineoplastic agents, some anesthetic and antibiotic drugs are in short supply. Dr. Link added that “70% of the 2010 shortages were sterile injectable agents, for which there is usually no alternative.” These drugs, especially older generics, are made by only a few companies. The manufacturing process is complex and costly—therefore not an economically attractive endeavor—and when a problem occurs, it is expensive to fix. “Companies want to put their resources to more profitable use, and when one [company] decides to discontinue a drug, there is no one to take up the slack,” said Dr. Link.

Consequences for Patients

Drug shortages pose devastating problems for patients and providers. “There are treatment delays, which are never a good idea. Often we have to substitute a less effective drug, and sometimes there is no substitute,” said Dr. Link.

At the briefing was Tom Kornberg, PhD, a research biologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma and scheduled to be treated with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine). The vinblastine was unavailable, however. Dr. Kornberg said he called on some of his contacts in the science community and eventually he located the agent.

Dr. Kornberg is in remission now. He is lucky to have the wherewithal and tenacity that enabled him to obtain the drug himself. The vast majority of patients with cancer, however, may not be so fortunate.

Dr. McBride added that in addition to treatment delays (affecting 80% of patients, according to a University of Utah survey), doses have been reduced, and medication errors are common. For example, when busulfan is unavailable, stem cell transplant cannot proceed, and when an oral drug is substituted for a parenteral one, errors are more likely.

In addition, the effect on clinical trials can be significant if the standard of care cannot be administered to act as the control because the standard regimen includes drugs that are in short supply.

As Dr. Link noted, we treat some cancers with an expectation of cure: leukemia, lymphoma, testis cancer, and sarcoma of bone and soft tissue. “If we can’t get the drugs, a disease we’ve treated successfully for many years is now rendered incurable, or significantly more difficult to treat. It is terribly discouraging and dispiriting.”

This is particularly evident in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which is curable in almost 90% of cases. The same is true for osteosarcoma, which is 65% curable with surgery and chemotherapy. All the drugs used for these two common childhood cancers are in short supply.

Causes Are Many, Solutions Needed

The causes of drug shortages are multiple and varied. Manufacturing difficulties, compliance problems, and obtaining raw materials can create significant delays. “For instance, if a company needs to change something in the production process, they can’t proceed until FDA approves,” Dr. Link said. “But it takes a while for FDA inspectors to visit the factory, so everything stops until the agents get there. And patients wait—and wait.”

The causes of drug shortages are multiple and varied. Manufacturing difficulties, compliance problems, and obtaining raw materials can create significant delays. “For instance, if a company needs to change something in the production process, they can’t proceed until FDA approves,” Dr. Link said. “But it takes a while for FDA inspectors to visit the factory, so everything stops until the agents get there. And patients wait—and wait.”

Corporate decisions to discontinue a drug, most likely because of insufficient profit, is a leading factor, as are changes in the industry itself, notably mergers. “Health care is a business, drug manufacturing is private enterprise, and there’s only so much that government and health-care providers can do to influence them,” said Dr. Link. “What kinds of incentives would encourage the industry to make drugs that are not so profitable? Tax breaks? Changing patent laws or distribution methods? Additional market exclusivity? Any of these might be worth thinking about.”

Aside from being expensive to research and bring to market, oncology drugs are unprofitable because of poor reimbursement. “Perhaps if CMS rethought its reimbursement policies, things might improve,” said Dr. Link.

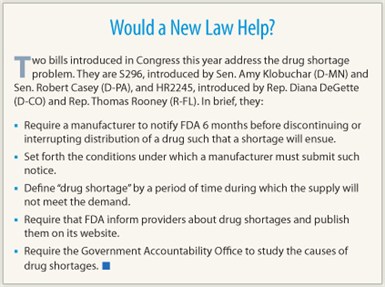

Would legislation help? “It might, but it could backfire. Six-month notification by FDA that a drug was to be discontinued temporarily or permanently would give providers warning of a shortage [see sidebar, “Would a New Law Help?”], but it also could lead to hoarding or stockpiling. And in the end, the agency has no real control over what the industry chooses to produce, or not.”

Financial Effect

The financial impact of drug shortages is also an issue. Substituting other medications may be more costly (and produce unexpected side effects, which are expensive to treat), and locating drugs that are in short supply is time-consuming and expensive. Stockpiling and hoarding by hospitals and distributors have become problems, both of which result in increased shortages elsewhere and “scalper” prices everywhere.

Further disturbing is the gray market that has emerged. Almost half (43%) of provider facilities said they have been contacted by gray market suppliers, although it is unknown how many hard-to-find drugs are “real” and how many are “gray.” If the latter, they may be counterfeit and possibly adulterated or weakened. Moreover, drugs on the gray market are always more expensive—often much more than the usual cost.

It’s impossible to be sure where gray market drugs come from, who manufactures them, how they are distributed, and how many hands they pass through before being administered to patients. Pharmacists cannot assay each dose, and although FDA has jurisdiction over counterfeit drugs, the agency cannot control widespread illegal activity. ■

Disclosure: Drs. Farber, McBride, Kornberg, and Link reported no potential conflicts of interest.