A Century of Progress

The text and photograph on this page are excerpted from a four-volume series of books titled Oncology Tumors & Treatment: A Photographic History, by Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS. The photo below is from the volume titled “The Radium Era: 1916–1945.” The photograph appears courtesy of Stanley B. Burns, MD, and The Burns Archive. To view additional photos from this series of books, visit burnsarchive.com.

By the 1930s, the dangers of radiation were well known. American Martyr’s to Science Through the Roentgen Rays, published in 1936, documented the dead heroes of American radiology, from Clarence Daly, Thomas Edison’s associate, to Elizabeth Fleischman, the only woman in the group, who was a U.S. Army radiographer in San Francisco. The extent of devastation to limbs and sterility was remarkable, skin reactions were quite astounding, and x-ray burns did not heal. A social faux pas in the history of radiology occurred at a 1920 dinner meeting of radiologists at which chicken was served. However, since most of the attendees had lost at least one hand, they could not cut their food. Others radiologists experimented with this new technology unaware of the dangerous repercussions. One such occurrence was the use of radium in combination with x-rays to bleach the skin of African Americans white by Robert Rees of San Francisco.

Thankfully, by 1904, lead had been found to be an ideal insulation against the deleterious effects of the rays. In 1907, the Friedlander Company offered a complete protective suit, including hood, gloves, and glasses. There was slower development in patient protection, as it was thought only the radiologist was in danger from constant exposure.

It should be noted that early x-ray therapy was given to a patient until there was an erythematous skin reaction, which usually took an extended period of time. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, protective measures for the patient were in place. The Coolidge bulb, a new, safer, more effective x-ray bulb, was developed in 1913, but most physicians were still using the early Crookes tube, as it was much less expensive. The safer tubes were not generally in use until the

late 1920s.

Early Protective Measure

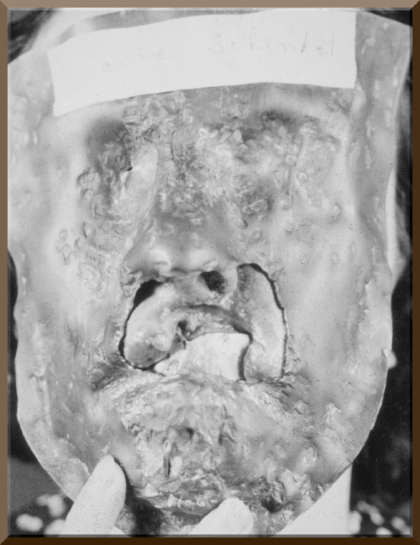

This photograph is of a young woman with a large piece of her upper lip eaten away by a carcinoma. Before undergoing excision and reconstructive surgery, she was treated with radiation. A two-piece protective lead mask was molded for her face. A mouthpiece of lead protected her gums and teeth.

She is pictured holding the mask to her face, and the only exposed area is the defect in her lip. After the radiation treatments, plastic surgeons repaired the defect. Her physician used a reconstructive flap technique, a pedicle graft fashioned from the upper chest wall to the side of her neck. The graft was cut from the chest and swung up to the lip while still being attached to the neck. Multiple operations resulted in closure of the defect. She underwent radiation and surgical procedures over a 2-year period. This multidisciplinary approach to cancer treatment and rehabilitation was a major step in providing a more normal life for survivors. ■