Colorectal cancer studies reported at this year’s ASCO meeting offered little in the way of practice-changing information, according to Axel Grothey, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. But they did confirm existing standards of care, he noted at the Best of ASCO® meeting in Seattle.

Colorectal cancer studies reported at this year’s ASCO meeting offered little in the way of practice-changing information, according to Axel Grothey, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. But they did confirm existing standards of care, he noted at the Best of ASCO® meeting in Seattle.

Perioperative Therapy for Rectal Cancer

Capecitabine (Xeloda) is at least as efficacious as fluorouracil (5-FU) when used in perioperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer, a phase III noninferiority trial found.1

A total of 392 patients were split into strata (adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy) and randomized to receive capecitabine or 5-FU (given intermittently in the neoadjuvant stratum) during radiation therapy. In the neoadjuvant stratum, the investigators found trends toward more tumor downstaging and more pathologic complete responses with capecitabine than with 5-FU.

After a median of 52 months, capecitabine-treated patients had better 5-year disease-free survival (67.8% vs 54.1%, P = .035) and overall survival (75.7% vs 66.6%, P = .052). An exploratory test for superiority of overall survival bordered on significant (P = .053).

Both agents were well tolerated, but a higher rate of hand-foot syndrome was seen with capecitabine, and a higher rate of leukopenia with 5-FU.

Capecitabine is clearly not inferior to 5-FU in this setting, Dr. Grothey pointed out. “Overall, I think that based on these data, capecitabine can replace 5-FU in the perioperative treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer, and a lot of us have already been doing that,” he commented.

Neoadjuvant Therapy for Rectal Cancer

Adding oxaliplatin to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer does not improve outcomes and increases gastrointestinal toxicity, finds the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) R-04 trial.2

Adding oxaliplatin to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer does not improve outcomes and increases gastrointestinal toxicity, finds the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) R-04 trial.2

The 1,253 patients with clinical stage II or III disease underwent 2-by-2 randomization for base chemotherapy (5-FU, here given continuously vs capecitabine) and for added oxaliplatin (with vs without)—each with the same radiation therapy.

The rate of surgical downstaging did not differ between the groups receiving 5-FU and capecitabine, or between those given oxaliplatin vs no oxaliplatin. The same was true for the rate of pathologic complete response. But the incidence of diarrhea of any grade with added oxaliplatin was more than doubled (15.4% vs 6.6%, P = .0001).

The findings provide yet more evidence that capecitabine is “an adequate substitute” for 5-FU in this setting, according to Dr. Grothey. “The addition of oxaliplatin did not improve outcome and added significant toxicities,” he said. “But we need longer follow-up to see whether this might translate into more time-related endpoints and long-term endpoints, such as overall survival and disease-free survival.”

Adjuvant Oxaliplatin for High-risk Stage II Colon Cancer

A pooled analysis of four NSABP trials found that adding oxaliplatin to adjuvant 5-FU chemotherapy may improve outcomes of high-risk stage II colon cancer.3 Of the four trials (C-05 through C-08), with a total of 3,000 patients, only one trial randomly assigned patients to oxaliplatin, Dr. Grothey cautioned.

Outcomes among all patients with stage II disease did not differ between oxaliplatin and no oxaliplatin. But in the high-risk subgroup, there were trends showing small absolute increments in 5-year adjusted estimates of disease-free survival (4.4%), time to recurrence (5.2%), and overall survival (3.5%) with addition of the drug.

“Now we are diving more and more into subgroups and pooled, unplanned analysis,” Dr. Grothey commented. “But I think there is still, from my personal perspective, some room for oxaliplatin in terms of using it in very select patients in high-risk stage II tumors.”

Cetuximab in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer with G13D KRAS Mutation

Patients with mutant KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer who have the G13D mutation may still derive benefit from cetuximab (Erbitux), based on a pooled exploratory analysis of data from first-line trials.4

Patients with mutant KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer who have the G13D mutation may still derive benefit from cetuximab (Erbitux), based on a pooled exploratory analysis of data from first-line trials.4

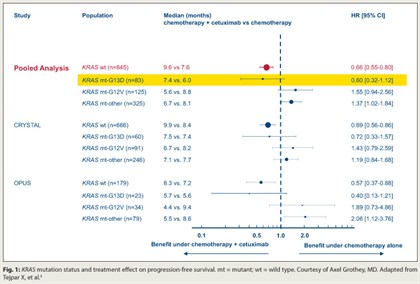

Five of six colorectal studies assessing chemotherapy with vs without addition of antibodies to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), such as cetuximab, have shown a benefit in patients with wild-type KRAS tumors, but no benefit and even potential detriment in patients with mutant KRAS, Dr. Grothey noted. In the new analysis, which pooled data from the CRYSTAL and OPUS trials, 6% of the 689 patients had the G13D KRAS mutation.

With chemotherapy alone, compared with their counterparts having other KRAS mutations, patients with the G13D mutation had poorer progression-free survival (HR = 1.54; P = .0847) and overall survival (HR = 1.39; P = .0988). But within the KRAS G13D mutation group, addition of cetuximab showed trends toward improved progression-free survival (HR = 0.60; P = .1037; Fig. 1) and overall survival (HR = 0.80; P = .37). The relative benefits mirrored those in patients with KRAS wild-type disease.

“It seems to be that patients with G13D KRAS mutations behaved similarly and they benefited in a similar way from cetuximab as patients with KRAS wild type,” Dr. Grothey commented.

Concordant Mutations Found in Primary, Metastatic Colorectal Cancers

An analysis finds primary colorectal cancers and their metastases show a high degree of concordance when it comes to mutations that are used for clinical decision-making and prognostication.5

In the sequencing analysis of 84 pairs of matched primaries and metastases, the primaries were more likely to have to have a BRAF mutation (P = .01) and less likely to have a p53 mutation (P < .001). Still, using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples, the investigators found a high concordance between the primaries and metastases for mutational status of RAS/BRAF (97.6%), PI3 kinase (98.8%), and p53 (95.2%). The value was 90.5% when all three were considered.

“This means, if we just focus on these mutations—which we do right now in our clinical practice—you do not need to biopsy metastases,” Dr. Grothey commented. “You can make do with the primary tumor.”

Colorectal Tumors and Liver Metastases Genetically Dissimilar

A study of a cancer mini‑

genome—1,264 genes relevant to the biology and treatment of cancer—shows that colorectal cancer primaries differ genetically from their liver metastases if one looks closely enough.6

Investigators analyzed formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from 21 patients who developed liver metastases, finding 8,405 genetic variations in the genes studied.

Analyses showed marked losses and gains of genetic variations going from the primary to the metastasis, regardless of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy; on average, tumors lost 70 variations and gained 83 variations.

“There was not a single tumor where primary tumor and metastasis were completely identical. All tumors had variations in the genetic makeup between primary tumor and metastasis, either as loss mutations or gain mutations,” Dr. Grothey commented.

“So we can now say, if we focus on KRAS and BRAF, that they are genetically similar,” he said. “But if you look at the whole genome in this analysis, primary tumors and metastases are different in their genetic makeup, and we know that because tumors respond heterogeneically to treatment.”

In this case, the investigators concluded that genetic analysis of metastases at the start of treatment may be better than relying on archival primary tumor. ■

Disclosure: Disclosure: Dr. Grothey has received research support from Genentech, Imclone/Eli Lilly, Daiichi, and Bayer.

SIDEBAR: Is G13D KRAS Mutational Status Ready for Prime Time?

SIDEBAR: Will Aflibercept Break Dry Spell in New Agents for Colorectal Cancer?

SIDEBAR: Risk-based Approach Needed for Stage II Colorectal Cancer

References

1. Hofheinz R, Wenz FK, Post S, et al: Capecitabine (Cape) versus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–based (neo)adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC): Long-term results of a randomized, phase III trial. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3504. Presented June 4, 2011.

2. Roh MS, Yothers GA, O’Connell MJ, et al: The impact of capecitabine and oxaliplatin in the preoperative multimodality treatment in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABP R-04. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3503. Presented June 4, 2011.

3. Yothers GA, Allegra CJ, O’Connell MJ, et al: The efficacy of oxaliplatin (Ox) when added to 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (FU/L) in stage II colon cancer. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3507. Presented June 4, 2011.

4. Tejpar S, Bokemeyer C, Celik I, et al: Influence of KRAS G13D mutations on outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3511. Presented June 4, 2011.

5. Vakiani E, Janakiraman M, Shen R, et al: Comparative genomic analysis of primary versus metastasis in colorectal carcinomas. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 10500. Presented June 6, 2011.

6. Vermaat JSP, Nijman IJ, Koudijs MJ, et al: Primary colorectal tumors and their metastasis are genetically not the same: Implications for choice of targeted treatment? 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3535. Presented June 6, 2011.