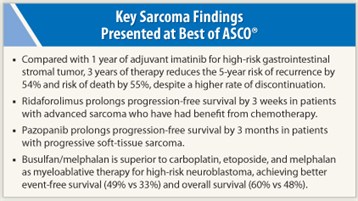

Novel approaches and agents reported at the ASCO 2011 Annual Meeting are improving outcomes in sarcoma, a heterogeneous disease with historically poor outcomes, according to William D. Tap, MD, Section Chief of Sarcoma Oncology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Dr. Tap presented the sarcoma abstracts at this year’s Best of ASCO Seattle meeting.

Novel approaches and agents reported at the ASCO 2011 Annual Meeting are improving outcomes in sarcoma, a heterogeneous disease with historically poor outcomes, according to William D. Tap, MD, Section Chief of Sarcoma Oncology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Dr. Tap presented the sarcoma abstracts at this year’s Best of ASCO Seattle meeting.

Adjuvant Imatinib in High-risk GIST: 1 vs 3 Years

In a phase III trial conducted by the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group and Sarcoma Group of the AIO, German (SSG XVIII) among patients with high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), outcomes were better with longer adjuvant imatinib therapy.1 A total of 397 patients with resected tumors were randomly assigned to 1 year vs 3 years of imatinib. Results showed that after a median follow-up of 54 months, patients in the 3-year group had better 5-year recurrence-free survival (65.6% vs 47.9%; HR = 0.46; P < .0001) and overall survival (92.0% vs 81.7%; HR = 0.45; P = .019). Those in the 3-year arm were more than twice as likely to discontinue treatment (31.8% vs 14.5%).

“This was a very nicely designed trial,” Dr. Tap commented, and it met its endpoints. “But…I think we will need more time (and events) to see what will happen to the overall survival data.”

The data are telling when it comes to tolerability, he noted. “We tend to think of [imatinib] as somewhat of a benign treatment, but it’s clear that if you ask patients to take this drug with no evidence of tumor, a significant proportion of them will stop taking it because of side effects. It is therefore critical to educate patients and physicians about the importance of remaining on treatment. To ensure this, physicians must remain vigilant about assessing and treating potential side effects.”

Ridaforolimus

The mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus improves progression-free survival in patients with advanced sarcoma who have had benefit from chemotherapy, according to results of the phase III SUCCEED trial.2 In this largest of trials to date in soft-tissue and bone sarcoma, 711 patients who achieved at least stable disease with chemotherapy were randomly assigned to ridaforolimus or placebo as maintenance therapy. Progression-free survival was superior with ridaforolimus (median = 17.7 vs 14.6 weeks; HR = 0.72; P = .0001). The rate of clinical benefit (complete response, partial response, or stable disease) was also better (40.6% vs 28.6%; P = .0009).

The mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus improves progression-free survival in patients with advanced sarcoma who have had benefit from chemotherapy, according to results of the phase III SUCCEED trial.2 In this largest of trials to date in soft-tissue and bone sarcoma, 711 patients who achieved at least stable disease with chemotherapy were randomly assigned to ridaforolimus or placebo as maintenance therapy. Progression-free survival was superior with ridaforolimus (median = 17.7 vs 14.6 weeks; HR = 0.72; P = .0001). The rate of clinical benefit (complete response, partial response, or stable disease) was also better (40.6% vs 28.6%; P = .0009).

Dr. Tap noted that the gain in progression-free survival was 3 weeks with independent radiographic review. “So this was statistically significant…but we have to question ridaforolimus’ true clinical value in sarcoma.”

Indeed, sarcoma is now recognized to be a group of 60 to 80 molecularly distinct diseases, and the trial’s molecular analyses were limited. “When we look at a trial of over 700 patients with sarcoma, we need to assess them according to histology-specific and molecular-specific subsets to really understand who to give this drug to and who not to give this drug to,” he maintained.

“Whether I will use this [drug] clinically is very difficult to answer,” Dr. Tap added. “I imagine there are some patients I may [give ridaforolimus], but for the majority of patients, it’s not something that I am ready to add into my general clinical practice.”

Pazopanib in Soft-tissue Sarcoma

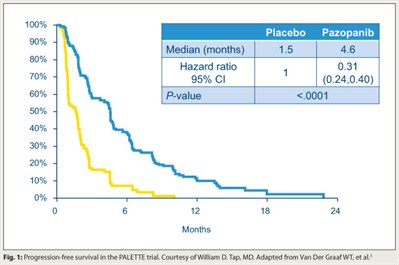

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib (Votrient) improves progression-free survival in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma that has progressed despite chemotherapy, concluded investigators who conducted the EORTC phase III PALETTE trial.3 In all, 369 patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to the drug (which targets VEGFR, PDGFR, and c-Kit) or placebo. Progression-free survival was longer with pazopanib than with placebo (median = 4.6 vs 1.5 months; HR = 0.31; P < .0001; Fig. 1). Overall survival was similar between the two groups.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib (Votrient) improves progression-free survival in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma that has progressed despite chemotherapy, concluded investigators who conducted the EORTC phase III PALETTE trial.3 In all, 369 patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to the drug (which targets VEGFR, PDGFR, and c-Kit) or placebo. Progression-free survival was longer with pazopanib than with placebo (median = 4.6 vs 1.5 months; HR = 0.31; P < .0001; Fig. 1). Overall survival was similar between the two groups.

Demographics differed slightly between groups: The pazopanib group had more leiomyosarcomas, a responsive subset based on the phase II data, and low-grade sarcomas, which in general have a better prognosis. “Whether or not [the differences] contributed to the outcomes is hard to know,” Dr. Tap commented.

Again, a key question to address is which patients will respond to the drug. “At Memorial Sloan-Kettering, for a few of the more sensitive subtypes, we are looking at pazopanib in combination with gemcitabine and docetaxel in the neoadjuvant setting, and the trial is very heavy with molecular correlates to try to predict which patients should respond and why,” he said.

Myeloablative Therapy for Neuroblastoma

A randomized trial found that BuMel (busulfan [Busulfex, Myleran] plus melphalan) is more efficacious than CEM (carboplatin, etoposide, and melphalan) as myeloablative therapy for high-risk neuroblastoma in patients responding to rapid COJEC induction therapy (cisplatin, vincristine, carboplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide).4

Of 1,577 patients who received the induction therapy, 43% had at least a partial response and were randomly assigned to myeloablative therapy with busulfan/melphalan or carboplatin, etoposide, and melphalan, followed by stem cell transplant, radiation therapy, and postconsolidation therapy. With a median follow-up of 3.5 years, compared with their counterparts given CEM, patients given BuMel had better event-free survival (49% vs 33%; P < .001) and overall survival (60% vs 48%; P = .003). The benefit of BuMel was greatest in patients with residual disease postinduction. BuMel had a better toxicity profile and was associated with lower rates of ICU admission and death.

According to Dr. Tap, response to CEM in the trial was lower than that seen historically in Children’s Oncology Group studies, possibly due to their use of a different induction regimen—the modified Memorial Sloan-Kettering N6 regimen. “Really the way to study this would be to compare the two regimens in a head-to-head trial, but I am not sure they will be able to do that, given the significant amount of resources that went into this trial,” he commented.

More than half of the patients didn’t make it to randomization because they had an inadequate response. “It’s those [initially unresponsive] patients that we need to affect,” Dr. Tap said. “As we move forward, it would be very nice to see if [emerging therapies] could be added up front to improve survival of these patients.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Tap reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SIDEBAR: Questions and Answers about Adjuvant Imatinib in GIST

References

1. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Hatrmann J, et al: Twelve versus 36 months of adjuvant imatinib (IM) as treatment of operable GIST with a high risk of recurrence: Final results of a randomized trial (SSGXVIII/AIO). 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract LBA1. Presented June 5, 2011.

2. Chawla SP, Blay J, Ray-Coquard IL, et al: Results of the phase III, placebo-controlled trial (SUCCEED) evaluating the mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus (R) as maintenance therapy in advanced sarcoma patients (pts) following clinical benefit from prior standard cytotoxic chemotherapy (CT). 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 10005 . Presented June 6, 2011.

3. Van Der Graaf WT, Blay J, Chawla SP, et al: PALETTE: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of pazopanib versus placebo in patients (pts) with soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) whose disease has progressed during or following prior chemotherapy—An EORTC STBSG Global Network Study (EORTC 62072). 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract LBA10002. Presented June 6, 2011.

4. Ladenstein RL, Poetschger U, Luksch R, et al: Busulphan-melphalan as a myeloablative therapy (MAT) for high-risk neuroblastoma: Results from the HR-NBL1/SIOPEN trial. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 2. Presented June 5, 2011.