Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and between 3% and 4% of all brain tumors, with an age-adjusted incidence rate of four cases per million persons per year. Approximately 1,500 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States; this rate is steadily increasing as the population ages, with nearly 50% of cases diagnosed in individuals older than 60.1-4

Induction therapy with high-dose methotrexate is the single most notable advance in patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL. Following induction therapy, consolidation is given to deepen and/or maintain responses, even in patients who attain a complete response or an unconfirmed complete response. Overall, the treatment program of sequential induction and consolidation attains cure in approximately 50% of patients, underscoring the fact that a major proportion of patients exhibit refractory PCNSL.

Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Arjun Patel, PharmD, BCOP

James Rubenstein, MD, PhD

Randomized IELSG32 Study

Recently, the 7-year results of the IELSG32 randomized trial were reported. Enrolled patients were randomly assigned to receive methotrexate plus cytarabine (arm A), or methotrexate, cytarabine, and rituximab (arm B), or methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix; arm C). A second randomization allocated patients with responsive or stable disease to consolidation with either whole-brain irradiation or carmustine, thiotepa, conditioned autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation.

MATRix plus consolidation therapy was associated with excellent long-lasting outcomes, with a 7-year overall survival of 21%, 37%, and 56% for arms A, B, and C, respectively. The results of this and other PCNSL studies stimulated us to delineate unresolved issues specifically regarding induction therapy, which is the focus of this article.

Shortcomings of Published Studies

Do the results of IELSG32 clearly demonstrate that MATRix is the best induction regimen for PCNSL?

As of this writing, the best induction or even the best postinduction strategy in PCNSL remains unknown. Although relapse rates are common following induction in patients who do not receive consolidation, the randomized controlled studies to support the MATRix approach over other strategies are lacking.

What we know is that PCNSL is extremely difficult to control after consolidation failure, leading to dismal outcomes. Moreover, there is a lack of sensitive disease detection methods (eg, measurable residual disease assessment in patients with complete remission or unconfirmed complete remission), and, thus, there is no reliable selection method for a best postinduction strategy. There is also no universally accepted duration and frequency of induction therapy (immense intertrial heterogeneity exists) and no consensus for the ideal target dose of “high-dose” methotrexate in different study protocols (only an agreement that a dose higher than 3.0 to 3.5 g/m2 is considered high-dose methotrexate). Due to these and other limitations in induction paradigms, conventional practice is to deliver additional therapy in the form of consolidation to all responders (who have at least stable disease).

The Missing Link

In order to confidently select the best induction regimen, one must know the impact of different induction responses—complete response/unconfirmed complete response, partial response, stable disease—on overall survival, independent of the postinduction strategy. Unfortunately, this particular aspect of treatment for PCNSL has not been rigorously studied. Intuitively, it is conceivable that deeper responses to induction (complete response > unconfirmed complete response > partial response > stable disease) may lead to better overall survival. We are not aware of a multicenter trial that has directly examined this question as a primary endpoint.

The primary endpoints of IELSG32 were complete response rate after induction (but not its impact on overall survival) and 2-year overall survival rate, which considers treatment in its totality (induction and consolidation). The primary endpoints of PRECIS3 were 2-year overall survival rates, again including the combined effects of both induction and consolidation. In the CALGB or Alliance 50202 study,2 the primary endpoint was complete response rate after induction, but similar to IELSG32, it did not analyze the direct impact on overall survival. To complicate matters further, with the exception of CALGB 50202, these studies allowed consolidation therapy in patients with responses at least as good as stable disease, which forms the premise for our next questions.

How does complete response after induction impact overall survival, and what is the relevance of the type of response (complete response vs unconfirmed complete response vs partial response vs stable disease) to overall survival?

Some consequential evidence shows that patients proceeding to consolidation with responses less than complete (ie, partial response or stable disease) have inferior outcomes. In the PRECIS study,3 despite a lower first complete response rate of 43% (compared with 54% for IELSG32), a higher proportion of patients received consolidation (69% vs 54%), whereas, unexpectedly, a greater percentage of patients had residual disease (ie, refractory PCNSL) after consolidation (42% vs 6%). Also, in the IELSG32 study, the highest overall survival was observed in patients receiving methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (arm C; MATRix) compared with methotrexate and cytarabine (arm A) or methotrexate, cytarabine, and rituximab (arm B); arm C had the highest complete response rates.

Additional Induction Regimens Besides MATRix

Which induction regimen is superior: MATRix (IELSG321) vs MT-R (high-dose methotrexate, temozolomide, and rituximab; CALGB/Alliance 502022) vs R-MBVP (rituximab, methotrexate, carmustine, teniposide, and prednisone; PRECIS3) vs R-MPV (rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, and vincristine)?4

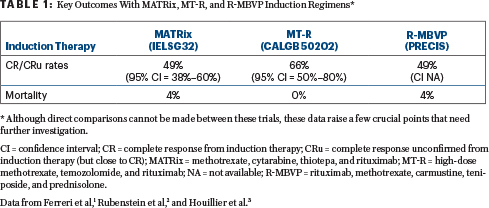

None of these regimens have been compared head-to-head. We need a randomized study to answer this question. The “winner induction regimen” would have the highest complete response rates (with fewest dropouts due to the induction regimen) and no treatment-related mortality. Table 1 displays the rates of complete response/unconfirmed complete response and mortality from three different phase II multicenter trials. In this table, we deliberately did not elaborate on single-center studies or multicenter studies that used induction agents unavailable in the United States (eg, teniposide). It is worth mentioning the R-MPV induction regimen because of its activity; however, many clinicians prefer to avoid procarbazine and vincristine in this setting.

We acknowledge that current data for overall survival are also influenced by postinduction therapy—but for which group of patients? Should patients in first complete response or unconfirmed complete response vs partial response vs stable disease be treated with a similar type of postinduction regimen? What is the number needed to treat to cure one patient who attains a complete response or unconfirmed complete response vs partial response vs stable disease with induction and proceeds to consolidation therapy? Based on current available data, it is difficult to know how much the induction response impacts overall survival. Due to these and other unanswered questions, it is impossible to conclude that intensive MATRix is the new standard induction regimen for PCNSL over other regimens.

Concluding Remarks

To overcome current shortcomings, it might be best to (1) compare commonly used induction regimens with the primary endpoint of first complete response or unconfirmed complete response and its direct impact on overall survival and (2) then perform a second randomization between consolidation with autologous transplantation vs nonmyeloablative therapy for patients in first complete response/unconfirmed complete response, partial response, and stable disease, to analyze the impact of different types of induction responses on outcomes with consolidation. In our opinion, administering the same postinduction therapy to all patients regardless of their induction response does not seem to be the best approach.

Also, combinations of high-dose methotrexate with targeted therapies (ie, ibrutinib, lenalidomide) or immunotherapies should be explored in clinical trials, with the goal of decreasing resistance to high-dose methotrexate and allowing more patients to proceed to consolidation with deeper responses. This approach is currently being pursued in the Alliance study, A51901, which investigates the incorporation of lenalidomide as well as nivolumab with a methotrexate and rituximab–based induction backbone in newly diagnosed PCNSL. There is also a need for the identification of robust molecular biomarkers for risk stratification and more rigorous interstudy comparisons. Finally, we believe that all the questions raised are important and must be answered before challenging a chemotherapy-related consolidation approach, maintenance chemotherapy, or immunomodulatory therapy.

To sum up: what is the best induction regimen in PCNSL? There is a lack of evidence to declare a single best induction regimen in this setting!

Dr. Abutalib is Co-Director of the Hematology and BMT/Cellular Therapy Programs and Director of the Clinical Apheresis Program at the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, City of Hope, Zion, Illinois; Associate Professor at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois; and Founder and Co–Editor-in-Chief, Advances in Cell & Gene Therapy. Dr. Patel is Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, City of Hope, Zion, Illinois. Dr. Rubenstein is Professor of Medicine, Hematology/Oncology, University of California, San Francisco, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Abutalib has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca. Dr. Patel reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Rubenstein reported financial relationships with Incyte and Nurix.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.

REFERENCES

1. Ferreri AJM, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E, et al: Long-term efficacy, safety and neurotolerability of MATRix regimen followed by autologous transplant in primary CNS lymphoma: 7-year results of the IELSG32 randomized trial. Leukemia. 36:1870-1878, 2022.

2. Rubenstein JL, Hsi ED, Johnson JL, et al: Intensive chemotherapy and immunotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: CALGB 50202 (Alliance 50202). J Clin Oncol 31:3061-3068, 2013.

3. Houillier C, Taillandier L, Dureau S, et al: Radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation for primary CNS lymphoma in patients 60 years of age and younger: Results of the Intergroup ANOCEF-GOELAMS randomized phase II PRECIS study. J Clin Oncol 37:823-833, 2019.

4. Omuro A, Correa DD, DeAngelis LM, et al: R-MPV followed by high-dose chemotherapy with TBC and autologous stem-cell transplant for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Blood 125:1403-1410, 2015.