Lodovico Balducci, MD, FASCO

Silvio Monfardini, MD

With the aging of the world population, geriatric oncology is becoming a mainstay. Over the past year in The ASCO Post, we published a couple of articles on the history of oncology, including one on the history of geriatric oncology in the United States and Europe. Our goal was to promote a common approach to older patients with cancer in clinical practice and in clinical research. We highlighted the most important achievements and the remaining challenges. We also highlighted previous setbacks, as we consider history the best teacher to overcome obstacles and mistakes of the past.1

In the present article, we will illustrate a successful and reproducible model of geriatric–oncologic integration in France. We will describe the French model of care for older patients with cancer and review the history that led to its success.

The unanimous conclusion of 3 decades of studies included the need to integrate oncologic and geriatric expertise in the management of older patients with cancer.1,2 The geriatric expertise allowed the practitioner to tailor the treatment to the individual characteristics of each patient, including life expectancy, resiliency, need for prehabilitation or rehabilitation, and social conditions. This approach has led to improved patient survival, decreased toxicity, and functional preservation in older patients with cancer.2

The sources of this history were the existing literature and interviews with experts. They included Dominique Maraninchi, MD, PhD, Chief of Medical Oncology at Marseille, and previous Chair of the Institut National du Cancer (INCa); Jean-PierreDroz, MD, a medical oncologist and Director of the Geriatric Oncology Program at the Léon-Bérard Cancer Center, Lyon, Jean Marie Brechot, MD, Secretary of INCa; Pierre Soubeyran, MD, PhD, a hematologist oncologist at the Institut Bergonie, Bordeaux; Etienne Brain, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at the Institut Curie-Hôpital René Huguenin, Paris; Muriel Rainfray, MD, retired Chief of Geriatrics at the University of Bordeaux, and past President of the French Geriatric Society, Bordeaux; Catherine Terret, MD, PhD, Co-Director of the Geriatric Oncology Program at the Léon Bérard Cancer Center, Lyon; and Didi Jasmin, widow of the late Claude Jasmin, MD, of Villejuif.

Keys to Success of the French Approach

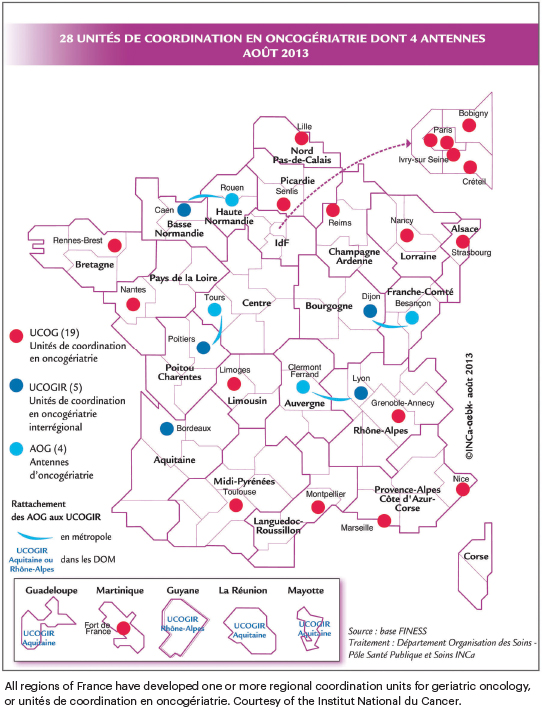

Three aspects of geriatric oncology in France deserve to be highlighted: first, the organization of Unités de Coordination en Onco-Geriatrie (UCOG, referred to here as regional coordination units for geriatric oncology)2,3; next, the development and implementation of an efficient screening tool (G8 questionnaire), vetted in theONCODAGE project4; and third, resources and support provided by the French government, which allowed the growth and success of the specialty of geriatric oncology as a nationwide project.

Unités de Coordination en Oncogériatrie: Over the past 2 decades, all regions of France have developed one or more regional coordination units for geriatric oncology, known as UCOG (see illustration on page 56). Each unit is directed by an oncologist and a geriatrician and charged with making recommendations for the outpatient and inpatient management of patients aged 75 and older. These units are managed by the Centres Hospitalièrs Universitaires and by the Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer.3,4 In 2005, the French National Cancer Institute funded 15 pilot units in different regions of France. The success of this experiment led to an expansion of these specialized units of care throughout the country in 2011.

The goals of UCOG in its original charter included the following: to disseminate the know-how of interaction between oncology and geriatrics teams; to make this expertise accessible to all elderly patients with cancer; to stimulate specific clinical and translational research; and to provide public and professional information about this new field of oncogeriatrics.

The influence of these units went well beyond the original goals of the group’s charter. The cross-seeding of oncologic and geriatric information prompted professionals in both specialties to become attuned to the individual needs of each patient. In this way, it promoted a new medical culture, germane to a demographic landscape where older individuals represent an increasingly large portion of the population and the majority of those using medical care. The basic principle of this culture holds age as a physiologic and social criterion, rather than a chronologic occurrence. In examining clinical results, patients must be judged according to their life expectancy and resilience rather than by any aging landmark and according to the availability of social support.

The regional coordination units for geriatric oncology are available to all individuals in France aged 75 and older. (This is because the majority of elderly people are older than 75, not because the number 75 is a landmark separating younger and older people.)

It is important to underscore that the French medical tradition and French history have long been particularly prone to embracing an aging culture. In 1670, Louis XIV (known as the Sun King) ordered the construction of the “Hôtel des Invalides,” which was inaugurated in 1678. This majestic building included a lodging and an infirmary for disabled and aged veterans and may be considered the first example of assisted living institutions. Today, these buildings are called “établissements d’hébergement pour personnes âgée dépendants” (EHPADs), or residential care for senior citizens. In 1673, the same king instructed his secretary of finances, Jean-Baptist Colbert, to institute “la caisse des invalides de la marine,” a pension system for disabled and aged sailors. That may be considered the first example of retirement income.

Together with the social assistance, the medical assistance of the aged soon became a major priority of the French medical system. Geriatrics was not recognized as a medical specialty in France until 2004. Nevertheless, since 1988, a special competence in geriatrics could be obtained with some specialty training. Since 2002, the French government has mandated that any hospital with an emergency room must include a mobile team for intervention in geriatric emergencies, a service of short hospitalization, a service of rehabilitation, and a service of long hospitalizations.

Clearly, France represents one of the most organized countries in the world for the care of the elderly. It is not surprising that the institution of the regional coordination units for geriatric oncology has been so successful, as has the diffusion of an aging culture that found its most fertile ground in France.

ONCODAGE Project: The ONCODAGE project4 allowed the UCOGs to adopt a common diagnostic approach for the rapid detection of age-related changes in patients 75 and older throughout France. The integration of oncologic and geriatric expertise hinged on a geriatric evaluation of all patients beyond a certain threshold age. This requirement was time-consuming and impacted the efficient delivery of care to older patients. The ONCODAGE project, financed by the French National Cancer Institute through government funds earmarked for geriatric oncology, enabled the whole nation to overcome this serious practical impediment. The project compared the accuracy and efficiency of two screening instruments—the Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (VES-13) and the G8 questionnaire—in identifying patients in need of a comprehensive geriatric assessment and concluded with the nationwide adoption of the G8 questionnaire.

The value of a common diagnostic approach is self-evident and cannot be overemphasized. In terms of patient care, the adoption of a common language to classify older patients allowed the standardization of care of these patients throughout the nation and the transferability of patient data in different institutions. In terms of clinical research, it allowed the implementation of rapid-learning databases, which are becoming the most practical research instruments in older individuals. Given the diversity of the older population, randomized clinical trials have an important but limited role in the study of cancer and age. They need to be complemented by retrospective trials, where the collection of data is homogeneous and reliable. In addition to being a model of oncogeriatric practice, France has become a data mine in oncogeriatric research around the world.

“To our knowledge, the French government has been the only government with the vision and prudence to prepare the medical community for the ‘gray tsunami’ in oncology.”— Lodovico Balducci, MD, FASCO, and Silvio Monfardini, MD

Tweet this quote

Government Resources: These results could not have been achieved without adequate resources. At the beginning of the year 2000, France’s then-President Jacques Chirac earmarked some of the country’s cancer institute funds for the development of geriatric oncology, and this foundation has been renewed throughout the years up to now. Under the direction of Dr. Maraninchi (then-Chair of the French National Cancer Institute),5 the first step the cancer institute took after receiving these funds was the organization of a board of geriatric oncology experts. The role of Chair was trusted to Claude Jasmin, MD, a pioneer in medical oncology at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejeuf (and throughout the world) and one of the earliest proponents of geriatric oncology. Jean-Pierre Droz, MD, of Centre Léon-Bérard, Lyon, was one of the original members of the board, and together with Dr. Jasmin, has been among the initial promoters of geriatric oncology in France.

Under the guidance of Dr. Jasmin, the board gathered a group of international experts and promoted professional education, public education, and research in geriatric oncology. Thanks to the activity of the board, a new generation of brilliant oncologists and geriatricians was welcomed into a new specialty.

To our knowledge, the French government has been the only government with the vision and prudence to prepare the medical community for the “gray tsunami” in oncology. Undoubtedly, this vision was fostered by several farsighted professionals who will be briefly described in the next section, as well as by a public culture that recognized a social duty to care for the elderly since at least the 17th century. However, it should be noted that the French experiment was made possible by the existence of a national health plan. This is inspired by a philosophy common to most Western European governments—that medicine is a service rather than a business and should be considered a basic human right.

Putting France’s Systems in Context: Care of Older Patients in the United States

A comparison of approaches to the care of older patients with cancer in France and the United States is very instructive. In the United States, there are centers of excellence in geriatric oncology that have produced some seminal bedside research.5,6 The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG),7 an international network of investigators, was also founded in the United States. CARG was envisioned by the late Arti Hurria, MD, of City of Hope, Duarte, California, and was funded by the U.S. National Cancer Institute. However, a national network for the care of the elderly is conspicuously absent in the United States; the Veterans Administration (VA) system represents a notable exception. Indeed, the VA is the only example of nationalized health care in the United States, and as such, it may direct its resources to areas of major need, even if they are not the most profitable.

A Short Story of Geriatric Oncology in France

After an overview of the French vision of geriatric oncology and its major achievements, it is also instructive to explore the steps through which this clinical and research network was constructed. The history of geriatric oncology in France includes the foresight, commitment, and efforts of individual practitioners and investigators. They have been able to define a mission, to advocate for funds, to design a blueprint, and to join forces toward a common goal. Even before the organization of a geriatric oncology network, French investigators were on the front lines in the study of older patients.8,9

We have already outlined how some pioneers had recognized an aging society and promoted the clinical study of cancer treatment in the elderly dating back to the early 1980s. The timeline on page 57 further enumerates many of these associated major events over the past 4 decades.

Key Achievements and Contributing Factors

To our knowledge, France is the only country in the world with a national geriatric oncology network and a common approach to patients with cancer aged 75 and older. To these impressive accomplishments, one must add the following:

The yearly economic support to the UCOG has been ranging from 160,000 euros to 250,000 euros, plus about 50,000 euros for interregional support and 90,000 euros for oncogeriatric antennas, with an overall cost of 5,200,000 euros per year.10

The number of older patients entered in institutional trials in France has been constantly increasing since 2007, almost reaching the level of patient enrollment in trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.11,12

Over the past 2 decades, in the area of geriatric oncology, scientific publications in peer-reviewed literature and scientific presentations from France at the ASCO Annual Meeting and the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress have outnumbered those of any other European country. More French scientists have been awarded ASCO’s B.J. Kennedy Award for Excellence in Geriatric Oncology than scientists from any other European country (including in 2022, when France’s Dr. Brain received this distinguished award).

Three essential factors that have contributed to the success of geriatric oncology in France are:

The presence of visionary professionals who predicted the need to prepare the medical system for the gray tsunami. This is not surprising because French medicine has been on the front line of medical developments throughout its history. In modern times, it is important that farsighted scientists know how to influence public opinion and political operators.

The presence of a nationalized health-care system able to host a national program and the governmental will to support such a program financially. The interaction of Drs. Droz, -Courpron, and Maraninchi, together with Dr. Droz’s efforts at public and professional education, was instrumental to obtaining these funds (see timeline).

The presence of an aging culture specific to France, nurtured by all political systems, from the “ancien régime” (15th to 18th centuries) onward. This culture allowed the seeds of geriatric oncology to sprout and grow.

Conclusions

France represents a shining example of rapid success in the creation of a national network of practice and research in geriatric oncology. This model appears reproducible in all countries enjoying the benefits of a nationalized health-care system. It may also be transferable to countries where medical care belongs to the private sector, such as the United States. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology may include a geriatric screening for patients 75 and older receiving cancer treatment, and the insurance companies may make the screening a precondition for reimbursement. It is not far-fetched to predict that the French model may become international, as countries from all continents have expressed a recent interest in geriatric oncology.

It is hoped that more oncology societies will emphasize the problem of cancer in the elderly during annual meetings and congresses, following the example of the strong and continuous ASCO involvement in this field. As our profession continues to grow and research in the area of geriatric oncology continues to develop, we salute the leaders of France for recognizing the need to prepare the medical system for the gray tsunami. Viva la France, et Viva Les Personnes Agees.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Monfardini and Dr. Balducci reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Monfardini S, Balducci L, Overcash J, et al: Cancer in older adults: The history of geriatric oncology, parts 1 and 2. The ASCO Post, October 10 and October 25, 2021

2. Monfardini S: Organizing the clinical integration of geriatrics and oncology, in Extermann M (ed): Geriatric Oncology, pp 451-461. New York, Springer, 2020.

3. Brechot JM: Aging and cancer: Addressing a nation’s challenge, in Extermann M (ed): Cancer and Aging: From Bench to Clinics, pp 158-163. Basel, Karger, 2013.

4. Soubeyran P, Bellera C, Goyard J, et al: Validation of the screening tool in geriatric oncology: The ONCODAGE project. J Clin Oncol 29(suppl):Abstract 9001, 2011.

5. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al: Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 29:3457-3465, 2011.

6. Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al: Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 118:3377-3386, 2012.

7. Rosko AE, Steer C, Chien LC, et al: The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) infrastructure: The clinical implementation core. J Geriatr Oncol 12:1164-1165, 2021.

8. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 346:235-242, 2002.

9. Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, et al: Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: IFCT-0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 378:1079-1088, 2011.

10. Brechot JM, Balandier C: Monitoring of the scheme for care and clinical research in oncogeriatrics. Available at https://www.e-cancer.fr. Accessed September 1, 2022.

11. Soubeyran P: How to organize geriatric oncology: The French model. SIOG Advanced Course on Geriatric Oncology, Treviso, Italy, 2017.

12. Brain E: Geriatric oncology in Europe: A commitment to improving cancer care for older patients. The ASCO Post, November 10, 2015.

Dr. Balducci is Professor of Oncology and Medicine at the University of South Florida College of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Geriatric Oncology, Senior Adult Oncology Program at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida. Dr. Monfardini is Chair of the European School of Oncology program on history of European Oncology, in Milan, Italy.