My patient with metastatic colon cancer was sitting across from me after being absent for several months. His cancer had been under excellent control on chemotherapy, but now he was having worse pain and shortness of breath. Despite our calls, he had not kept his appointments. We were 6 feet apart, masked, and goggled. “I have been afraid to come in,” he said. “I don’t want to get COVID-19.”

At this point in the pandemic, we have all had unfortunate experiences like this one. COVID-19 has upended the way we practice and the way patients with cancer participate in their care, seemingly overnight. Something as routine as an office visit and a physical exam is now fraught with risk. Patients worry that life-saving treatment could also make them more susceptible to a deadly virus. Oncology care is more complex than ever.

Kathryn Hudson, MD

Redefining Quality Oncology Care

In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, quality oncologic care is being redefined. Now, quality is synonymous with providing an excellent standard of oncologic care while maximizing safety from COVID-19, for our patients and for us. This has required sweeping systemic changes for cancer centers and hospitals, as well as myriad practice pattern changes for all physicians. Many of the changes are likely here to stay and will improve the quality of care, even when COVID-19 is a distant memory. Other changes, while necessary, may have unintended or unavoidable negative consequences.

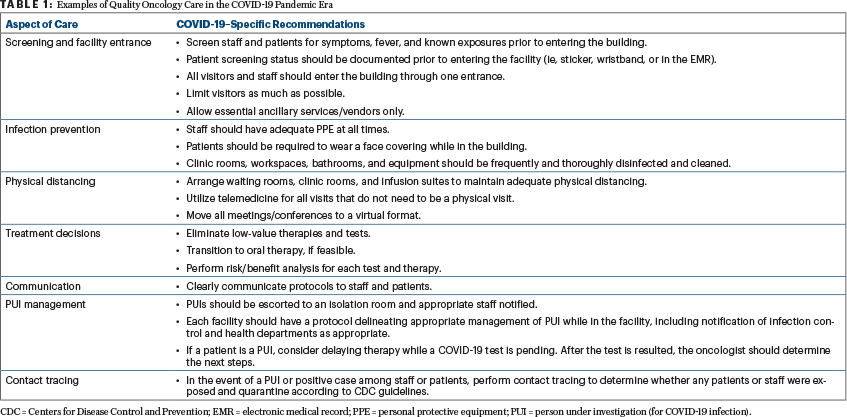

Cancer does not stop for COVID-19. It is essential for patients to receive appropriate cancer treatment, especially as the pandemic stretches on. Now, quality oncology care incorporates the following essential elements: screening, personal protective equipment (PPE), physical distancing, incorporation of video conferencing, contact tracing, triage, and safe management of persons under investigation for COVID-19 infection (Table 1).

Patients and staff must be screened for COVID-19 symptoms and fever before they enter a cancer center. Staff must have adequate PPE at all times, and patients should be required to wear a face covering while in the cancer center. Visitors and nonessential ancillary vendors should be admitted to the cancer facility only if absolutely necessary. Infusion and waiting rooms must be rearranged to maximize physical distancing. Clinic rooms and workspaces must be cleaned frequently, and all protocols should be clearly communicated to patients and staff. If a patient does not need to be examined, the visit should be conducted through telemedicine. Tumor boards and meetings should be held virtually.

Each center should have a plan in place for treating persons under investigation or patients who are COVID-19–positive. In the event a patient or staff is a person under investigation, this individual should be escorted to a designated isolation room in the facility or outside, and testing should be arranged.

If a patient or staff member tests positive for COVID-19, infection control and the appropriate health department should be notified. Appropriate contact tracing should be performed to determine whether any patient or staff member was exposed, and those exposed should be quarantined per the guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that, for those working with immunocompromised patients, there is no health-care exception to the 14-day period. All these changes drastically reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission among our patients and staff and allow us to care for patients safely.

Weighing Benefits and Risks of Cancer Screening and Treatment

For oncologists to provide quality care in the COVID-19 era, we must constantly weigh the benefits of each test and treatment with the risk of exposure and susceptibility to COVID-19. Hippocrates’ instruction, “First, do no harm,” is more pertinent than ever.

Previously simple decisions can now be arduous. Should we put off that mammogram or colonoscopy? Should I perform a physical exam or just treat based on symptoms? If patients have a fever but also a negative COVID-19 test, are they safe to come into the cancer center for evaluation?

“COVID-19 has upended the way we practice and the way patients with cancer participate in their care, seemingly overnight.”— Kathryn Hudson, MD

Tweet this quote

Therapy-related decisions are affected as well. Is adjuvant chemotherapy for a patient with stage II lung cancer worth the survival benefit? Would it be better to give 3 months rather than 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy for intermediate-risk colon cancer? For hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is on the upswing, and adjuvant chemotherapy is on the downswing. There are no easy answers.

Positive and Negative Practice Consequences

Many pandemic practice changes are patient-centered and will lead to long-lasting improvement in the quality of oncology care. Thanks to telemedicine, many patients who live in rural areas have access to multidisciplinary or specialty care for the first time. Many patients like the convenience of telemedicine, especially those for whom travel is difficult or for whom time for appointments is limited. Oncologists have learned that it can be safe to discharge a patient on the same day after surgery and that surveillance imaging does not need to be done as frequently. Virtual tumor boards are more convenient and therefore better attended. These changes are all welcome evolutions to oncology care and hopefully will persist.

In our necessary efforts to decrease the transmission of COVID-19, some pre–COVID-19 quality standards have worsened. At the beginning of the pandemic, it was recommended that cancer screening be postponed to preserve health-care resources and reduce patients’ contact with health-care facilities. As a result, there is a steep decline in new cancer diagnoses compared with previous years.1 Unfortunately, this will likely lead to presentation of cancer at later stages and thus worse clinical outcomes.

Another unintended consequence has been the increased difficulty of managing common oncologic complications on an outpatient basis. In many communities, patients are more likely to be referred to a hospital for evaluation of fever or dyspnea, because it is the fastest way to obtain a COVID-19 test with rapid results.

The Humanistic Side of Medicine

A critical and often overlooked part of quality oncology care is the humanistic side of medicine. One of the greatest losses our patients (and ourselves) have suffered during COVID-19 is the loss of touch, presence, and connection. Staying apart decreases the risk of COVID-19 transmission, but it also means that patients’ family members cannot come to their visit or sit with them in the infusion suite. Friends and family are also less likely to visit or help around the house. Now, we often discuss poor prognoses or recommend hospice over a screen, making it impossible to show how much we care by holding a patient’s hand. Patients are isolated and lonely at a time that is already emotionally challenging, which in turn may increase the risk for anxiety or depression.

Compounding this issue is that patients are less likely to have access to hands-on supportive care therapies such as physical therapy, home nursing, and in-home palliative care. Unfortunately, the loss of touch and social connection has been part of the collateral damage of the pandemic.

“Cancer does not stop for COVID-19. It is essential for patients to receive appropriate cancer treatment, especially as the pandemic stretches on.”— Kathryn Hudson, MD

Tweet this quote

Lessons Learned

COVID-19 has transformed oncology care in this country in several short months. The oncology community has rapidly risen to this enormous challenge, creating systems and tools to improve quality cancer care while decreasing the risk of transmission. Cancer centers and physicians have demonstrated agility, making systemic and patient-centered changes that increase safety and often the overall value of care. Other consequences, including health-care rationing and patient isolation, will likely have negative outcomes. It is essential that quality data be collected, so we can evaluate the long-term effects of these changes on patients with cancer and oncology care. Let us learn from our COVID-19 experience, so we can improve cancer care in the post–COVID-19 world.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Hudson has had a consulting or advisory role with Daiichi Sankyo.

REFERENCE

1. Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, et al: Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2017267, 2020.