Syed A. Abutalib, MD

Here is a brief look at the study findings and clinical implications of several recent and important clinical trials in neoplastic hematology. Attention is focused on myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Myelodysplastic Syndromes

Clinical Trial: Randomized phase III study of lenalidomide (Revlimid; n = 160) vs placebo (n = 79) in patients with red blood cell transfusion–dependent lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who were ineligible for or refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents1

Question Asked: What is the role of lenalidomide in blood cell transfusion–dependent patients with International Prognostic Scoring System (World Health Organization 2008 criteria) lower-risk (low- and intermediate-1 risk categories) non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes? The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of red blood cell transfusion independence for ≥ 8 weeks.

Study Conclusion: Red blood cell transfusion independence of ≥ 8 weeks was achieved in 26.9% and 2.5% of patients in the lenalidomide and placebo groups, respectively (P < .001). Median onset of blood cell transfusion independence was at 10.1 weeks; 90% of patients responded within 16 weeks. Median duration of blood cell transfusion independence with lenalidomide was 30.9 weeks (95% confidence interval [CI], 20.7–59.1 weeks). Higher response rates were observed in patients with lower baseline endogenous serum erythropoietin ≤ 500 mU/mL (34.0% vs 15.5% for > 500 mU/mL). Achievement of blood cell transfusion independence of ≥ 8 weeks was associated with significant improvements in health-related quality of life (P < .01).

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Venous thrombosis was reported in five patients (3.1%) while on lenalidomide treatment; no pulmonary embolism was observed. While on treatment, four patients (2.5%) in the lenalidomide group and two patients (2.5%) in the placebo group died.

Clinical Implications: Overall, these data support the possible clinical benefits of lenalidomide in lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes. Exploratory analyses to identify patients more likely to respond to lenalidomide showed that a higher proportion of patients (42.5%) with erythropoietin ≤ 100 mU/mL and prior use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents achieved blood cell transfusion independence of ≥ 8 weeks. Prospective studies are warranted to validate this observation and to substantiate it with additional biologic and molecular data.2 Patients with higher endogenous erythropoietin levels may be less responsive to lenalidomide.3

Data have suggested that the combination of lenalidomide and erythropoietin may be beneficial in patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes who are resistant to erythropoietin.4 Prior blood cell transfusion burden and use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and possibly endogenous serum erythropoietin levels, may be used to select patients who are more sensitive to lenalidomide therapy. Median overall survival has not yet been reached in this study.1 Long-term (≥ 5 years) follow-up data for overall survival is ongoing.

Multiple Myeloma

Clinical Trial: Association of minimal residual disease with superior survival outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma5

Question Asked: What is the significance of minimal residual disease in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma?

Study Conclusion: Fourteen studies (n = 1,273) reported data on the impact of minimal residual disease on progression-free survival, and 12 studies (n = 1,100) assessed the impact of minimal residual disease on overall survival. Results were reported specifically in patients who had achieved conventional complete response in 5 studies for progression-free survival (n = 574) and 6 studies for overall survival (n = 616). Minimal residual disease–negative status was associated with significantly better progression-free survival overall (hazard ratio [HR], 0.41; 95% CI, 0.36–0.48; P < .001) and in studies specifically looking at patients who achieved complete remission (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.34–0.56; P < .001). Overall survival was also favorable in minimal residual disease–negative patients overall (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46–0.71; P < .001) and in patients who achieved complete remission (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.33–0.67; P < .001).

Clinical Implications: It is important to note that this was a meta-analysis (1990–2016) and not a prospective randomized trial. This analysis did not account for the type of minimal residual disease test used in each of the studies analyzed. Approaches to testing varied widely; the sensitivity of different minimal residual disease–testing protocols also varied.

However despite these caveats, the study has a powerful message: minimal residual disease–associated results were method-agnostic; in other words, if minimal residual disease is undetectable with a specific level of sensitivity, the results have similar significance irrespective of the method utilized. In my opinion, this study further lends support of incorporating minimal residual disease assessment (by an easily assessable and broadly applicable method) in clinical trials and subsequently—and hopefully soon—in routine clinical practice.

Clinical Trial: A multicenter (18 countries), randomized, open-label, phase III POLLUX trial,6 which included 569 patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who were randomized (in a 1:1 ratio) to receive either lenalidomide or dexamethasone (control group; n = 283) or similar therapy in combination with daratumumab (Darzalex; daratumumab group; n = 286)

Question Asked: Is the addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone a better therapeutic strategy than lenalidomide and dexamethasone in persons with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma? The primary endpoint was progression-free survival.

Study Conclusion: At a median follow-up of 13.5 months in a protocol-specified interim analysis, 169 events of disease progression or death were observed (in 53 of 286 patients [18.5%] in the daratumumab group vs 116 of 283 patients [41.0%] in the control group; HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.27–0.52; P < .001 by stratified log-rank test). The Kaplan-Meier rate of progression-free survival at 12 months was 83.2% (95% CI, 78.3%–87.2%) in the daratumumab group, as compared with 60.1% (95% CI, 54.0%–65.7%) in the control group. A significantly higher rate of overall response was observed in the daratumumab group than in the control group (92.9% vs 76.4%, P < .001), as was a higher rate of complete response or better (43.1% vs 19.2%, P < .001). Additionally, in the daratumumab group, 22.4% of the patients had results below the threshold for minimal residual disease (1 tumor cell/105 white cells), as compared with 4.6% of those in the control group (P < .001); results below the threshold for minimal residual disease were associated with improved outcomes.

The most common adverse events of grade 3 or 4 during treatment were neutropenia (51.9% in the daratumumab group vs 37.0% in the control group), thrombocytopenia (12.7% vs 13.5%), and anemia (12.4% vs 19.6%). Daratumumab-associated infusion-related reactions occurred in 47.7% of the patients and were mostly grade I or II.

Clinical Implications: Daratumumab was associated with infusion-related reactions and a higher rate of neutropenia. Such infusion reactions were mostly mild and were most common with the first infusion; they rarely resulted in drug discontinuation. Lenalidomide-refractory patients were excluded from the study. Patients who were older than 75 years of age or whose body mass index was less than 18.5 kg/m2 received dexamethasone at a dose of 20 mg weekly at the discretion of their physician. In my opinion and from a practical standpoint, the results of the CASTOR trial7 and now the POLLUX trial6 strongly favor the use of a daratumumab-based triplet regimen in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who are not resistant or intolerant to bortezomib (Velcade) and lenalidomide, respectively.

Leukemia

Clinical Trial: Analysis of progression-free and overall survival in 554 patients from 2 randomized chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) trials of the German CLL Study Group (CLL8: fludarabine and cyclophosphamide [FC] vs FC plus rituximab (Rituxan); CLL10: FC plus rituximab vs bendamustine plus rituximab) according to the end of therapy minimal residual disease assessed in peripheral blood at a threshold of 10−4 and International Workshop on CLL Criteria8,9

Question Asked: What is the value of minimal residual disease assessment, together with the evaluation of clinical response, in CLL after completion of therapy?

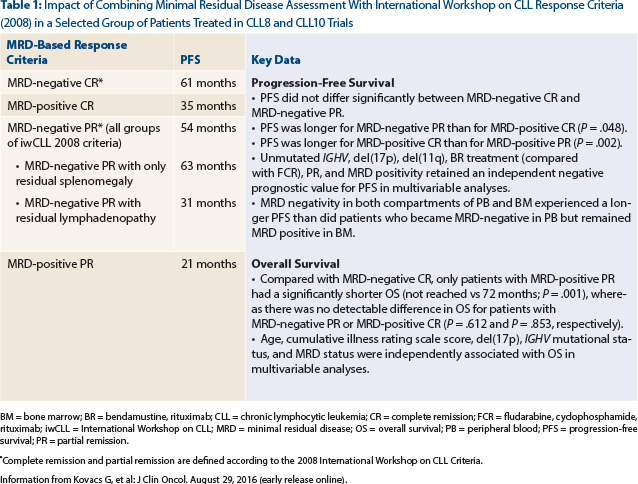

Study Conclusion: Patients with minimal residual disease–negative complete remission, minimal residual disease–negative partial response, minimal residual disease–positive complete remission, and minimal residual disease–positive partial response experienced a median progression-free survival from a landmark at thr end of therapy of 61 months, 54 months, 35 months, and 21 months, respectively (Table 1). It is intriguing, that patients with minimal residual disease–negative partial response who had residual splenomegaly had a similar progression-free survival (63 months) compared with patients with minimal residual disease–negative complete remission (61 months; P = .354), whereas patients with minimal residual disease–negative partial response with residual lymphadenopathy had a shorter progression-free survival (31 months; P < .001).

Clinical Implications: It is important to recognize that there remains a lack of broader applicability and standardization of minimal residual disease technique.8 Recently, the European Medicines Agency published a guideline on the use of minimal residual disease as an intermediate endpoint in CLL studies10; minimal residual disease quantification, if performed in a similar manner as in this particular study,8 would allow for improved progression-free survival prediction in both patients who achieve partial response and complete remission and would support its application in all responders to conventional chemo(immuno)therapy. In contrast to residual lymphadenopathy, persisting splenomegaly, up to 16 cm, does not impact outcomes in patients with minimal residual disease–negative partial response. Table 1 summarizes additional important data reported by investigators of this excellent study. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Abutalib reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Dr. Abutalib is Assistant Director, Hematology & Bone Marrow Transplantation Service, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Zion, Illinois. He also is the guest editor of The ASCO Post’s “Hematology Expert Review,” an occasional feature that includes a case report detailing a particular hematologic condition followed by questions, answers, and expert commentary.

1. Santini V, Almeida A, Giagounidis A, et al: Randomized phase III study of lenalidomide versus placebo in RBC transfusion-dependent patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes and ineligible for or refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. J Clin Oncol 34:2988-2996, 2016.

2. Sardnal V, Rouquette A, Kaltenbach S, et al: A G polymorphism in the CRBN gene acts as a biomarker of response to treatment with lenalidomide in low/int-1 risk MDS without del(5q). Leukemia 27:1610-1613, 2013.

3. Wallvik J, Stenke L, Bernell P, et al: Serum erythropoietin (EPO) levels correlate with survival and independently predict response to EPO treatment in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Eur J Haematol 8:180-185, 2002.

4. Toma A, Kosmider O, Chevret S, et al: Lenalidomide with or without erythropoietin in transfusion-dependent erythropoiesis-stimulating agent-refractory lower-risk MDS without 5q deletion. Leukemia 30:897-905, 2016.

6. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al: Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 375:1319-1331, 2016.

7. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al: Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 375:754-766, 2016.

9. Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al: Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 111:5446-5456, 2008.

10. European Medicines Agency: Guideline on the use of minimal residue disease as an endpoint in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia studies. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/12/WC500179047.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2016.