In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), continued long-term therapy that prevents both progression to accelerated-phase disease and the emergence of resistance may be thought of as an “operational” or “functional” cure. However, long-term disease control without the requirement for continuous treatment is currently being sought, and there is much ongoing investigation in developing strategies to eradicate leukemic stem cells.

Case Study

Timothy Hughes, MD, MBBS, of the Centre for Cancer Biology, Adelaide, South Australia, introduced this discussion with a case of a 30-year-old female patient with CML. She is currently receiving imatinib (Gleevec) at 600 mg/d and had achieved a complete cytogenetic response by 18 months. However, she has not yet achieved a major molecular response. The patient hopes to start a family soon, and was looking to her clinician for guidance as to when it would be safe to proceed. She questioned if switching to nilotinib (Tasigna) or dasatinib (Sprycel) would provide a greater chance of achieving a stable response, offering an opportunity for her to stop therapy while attempting a pregnancy.

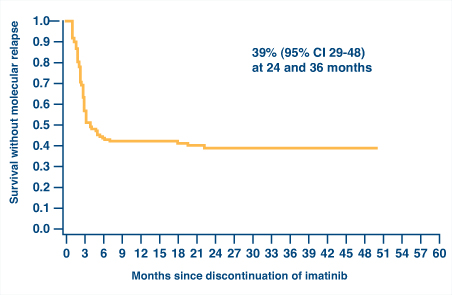

It is desirable to achieve a deep molecular response in this situation based on observations from the French STIM (Stop Imatinib) study (Fig. 1)1 and the Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group CML8 trial of imatinib withdrawal.2 Both studies have shown that about 40% of patients who achieved a stable complete molecular response of at least 2 years duration could maintain that response after discontinuation of imatinib. Thus, these data may provide both hope and guidance for the patient.

Greater Stability with Early Major Molecular Response

However, the patient has not achieved a major molecular response. What are her chances of being free of disease progression? If one looks at event-free survival data from the 18-month landmark analysis of the IRIS study, her probability of being progression-free with a complete cytogenetic response is 86%; this increases to 95% if she achieves a major molecular response.3 More importantly, what are her chances of losing her complete cytogenetic response? In the same 18-month landmark analysis, 29% of patients who achieved transcript levels between 0.1% and 1%, which is consistent with complete cytogenetic response without a major molecular response, lost their complete cytogenetic response over the subsequent 5.5-year period. In contrast, only 4% of patients who had achieved a major molecular response lost their complete cytogenetic response during that time frame. Data from Hammersmith Hospital were similar.4 These data provide good reasons for why one would want this patient to achieve a major molecular response prior to considering treatment cessation.

Achievement of a major molecular response by 12 or 18 months is associated with a low risk of progression. Long-term follow-up of 181 patients with chronic-phase CML in Adelaide who were treated with first-line imatinib suggests that earlier achievement of a major molecular response also leads to greater stability of response.5 In this study, the probability of achieving a confirmed complete molecular response (defined as a complete molecular response on two consecutive tests) by 60 months was determined for patients who achieved a major molecular response. Patients who achieved a major molecular response by 6 months had a high probability (93%) of achieving complete molecular response by 5 years. As the time to achieve major molecular response became longer, the chances of achieving complete molecular response was considerably reduced (ie, 69% if major molecular response was achieved between 6 and 12 months and 37% if major molecular response was achieved between 12 and 18 months). None of the patients who achieved a major molecular response after 18 months went on to achieve a complete molecular response.

“So, this woman is facing the reality that if she continues her current therapy, her chances of achieving complete molecular response are close to zero,” noted Dr. Hughes. “Therefore, she would not even get to the point where you would be even going to consider stopping, if your focus was to maintain durable complete molecular response.”

ENESTcmr Trial

This brought up the discussion of the ENESTcmr study. This randomized trial focused on the idea that, in patients who are still BCR-ABL–positive after at least 2 years of imatinib therapy, it might be beneficial to switch to nilotinib due to its greater potency. By switching, one might be able to induce more patients to achieve deep molecular responses, including complete molecular response. Indeed, of patients on study at 12 months, twice as many who crossed over to nilotinib achieved a confirmed complete molecular response compared to those remaining on imatinib (14.9% vs 6.1%, respectively; P = .04).6 Of particular relevance to the patient case, in patients who had not achieved a major molecular response at baseline, 75% of those switching to nilotinib achieved a major molecular response within 12 months compared to 36% of those remaining on imatinib. Even more convincingly, of patients not in major molecular response or better at baseline who were switched to nilotinib, 25.0% had achieved a deep molecular response (4.5-log reduction in BCR/ABL, or MR4.5) within 12 months compared to 3.6% of those remaining on imatinib (P = .040). Thus, it is possible in some cases to take a patient who is hovering at a transcript level greater than 0.1% and get him to a deep molecular response within a year.

CML8 Study

Dr. Hughes commented that in the CML8 study, patients who had a molecular relapse after imatinib cessation were started back on their previous therapy at their last effective dose, which rapidly restored complete molecular response; there was no need to switch to a more potent drug.2 Importantly, there have been no cases of progression, mutation, or resistance in these patients. All patients remained in major molecular response at last follow-up; 64% never lost their major molecular response, and 86% were in complete molecular response at their latest visit.

“I think that in the confines of a closely monitored clinical trial, where you have documented stable complete molecular response for 24 months, where you follow them with monthly polymerase chain reaction with a sensitive test, it seems to be appropriate and safe to stop therapy and watch those patients,” Hughes noted. “But that should not be translated into stopping in a situation where you have suboptimal molecular monitoring or it is not possible or realistic to monitor those patients very, very closely.”

Dr. Hughes concluded that the evidence suggests that switching would improve the patient’s chances of achieving a complete molecular response or deep molecular response, which would be a good platform for stopping for an attempted pregnancy. Although it is unknown whether the chances of sustained complete molecular response off-therapy would be improved, her chances are very low if she remains on imatinib.

Jorge Cortes, MD, asked whether one could just increase the dose of imatinib in this case. Dr. Hughes agreed that, based on data from the ENESTnd study, it could increase the probability of achieving a major molecular response. There was some discussion, however, regarding the need to consider the speed of obtaining the response, with imatinib acting more slowly. Use of interferon always remains an option during pregnancy. ■

References

1. Mahon F-X, Réa D, Guilhot J, et al: Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who have maintained complete molecular response: Update results of the STIM study. Blood 118(suppl 21):Abstract 603, 2011.

2. Ross M, Branford S, Seymour J, et al: Frequent and sustained drug-free remission in the Australasian CML8 trial of imatinib withdrawal. Haematologica 97(suppl 1):Abstract 0189, 2012.

3. Hughes TP, Hochhaus A, Branford S, et al: Long-term prognostic significance of early molecular response to imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: An analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS). Blood 116:3758-3765, 2010.

4. Marin D, Milojkovic D, Olavarria E, et al: European LeukemiaNet criteria for failure or suboptimal response reliably identify patients with CML in early chronic phase treated with imatinib whose eventual outcome is poor. Blood 12:4437–4444, 2008.

5. Branford S, Lawrence R, Grigg A, et al: Long term follow up of patients with CML in chronic phase treated with first-line imatinib suggests that earlier achievement of a major molecular response leads to greater stability of response. Blood 112(suppl 11):Abstract 2113, 2008.

6. Hughes TP, Lipton JH, Leber B, et al: Complete molecular response (CMR) rate with nilotinib in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) without CMR after 2 years on imatinib: Preliminary results from the randomized ENESTcmr trial of nilotinib 400 mg twice daily (BID) vs imatinib. Blood 118(suppl 21):Abstract 606, 2011.