The U.S. health-care system, with its rapidly aging population, faces a multitude of difficult clinical and financial challenges in caring for its burgeoning population of older patients with cancer. Moreover, age-related social and medical issues among older patients need to be addressed by a multidisciplinary approach, increasing the demand for oncologists who specialize in geriatric care.

A large question looms over the cancer community: With an impending oncology workforce shortage, will there be ample geriatric oncologists to care for the special needs of our elderly patients?

Education Needed

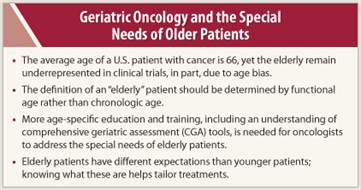

The relatively new discipline of geriatric oncology remains challenged by misperceptions about treating older patients. “The average age of a patient with cancer in the United States is 66, and yet our age perception of cancer doesn’t really correspond with the reality. The view of patients with cancer presented in mass media is much younger—you rarely see an older patient in an advertisement,” said geriatric oncologist Hyman Muss, MD, speaking with The ASCO Post. Dr. Muss is Professor of Medicine at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The relatively new discipline of geriatric oncology remains challenged by misperceptions about treating older patients. “The average age of a patient with cancer in the United States is 66, and yet our age perception of cancer doesn’t really correspond with the reality. The view of patients with cancer presented in mass media is much younger—you rarely see an older patient in an advertisement,” said geriatric oncologist Hyman Muss, MD, speaking with The ASCO Post. Dr. Muss is Professor of Medicine at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

“The fact that 60% of cancer survivors in our nation are aged 65 years and older presents challenges that we need to address, in part, by educating physicians to recognize the special issues that pertain to older patients with cancer. For instance, we don’t know how older people will respond to the newer chemotherapy regimens and biologics that have been tested in younger patients,” explained Dr. Muss.

According to Dr. Muss, despite the fact that they make up the majority of our cancer population, geriatric oncology patients are sorely underrepresented in cancer clinical trials. Studies looking at a number of demographic and socioeconomic factors show that patients aged 65 and older are less likely to be offered access to clinical trials. “That is a clear example of age bias,” said Dr. Muss.

He cited overly strict inclusion criteria and lack of motivation to enroll older patients into trials as two reasons for this lack of participation. “However, another reason for lack of participation falls on the shoulders of physicians, many of whom are unjustifiably concerned about subjecting their older patients to treatment-related toxicities,” said Dr. Muss.

He cited overly strict inclusion criteria and lack of motivation to enroll older patients into trials as two reasons for this lack of participation. “However, another reason for lack of participation falls on the shoulders of physicians, many of whom are unjustifiably concerned about subjecting their older patients to treatment-related toxicities,” said Dr. Muss.

He pointed out that studies in geriatrics show that many older patients with cancer want access to the cutting-edge treatments afforded by clinical trials, and that with proper safety parameters, they fare just as well as their younger counterparts.

Age Barriers

Dr. Muss opined that although we have made progress in addressing issues of age bias, the phenomenon still exists within the cancer care community. He acknowledged that treatment decisions are more difficult in older patients, many of whom are frail and have serious comorbidities. “But if a 75-year-old patient with breast cancer is otherwise fit, she should be offered the same treatment options as a younger woman,” stressed Dr. Muss.

For instance, data indicate that older women with breast cancer are less likely to be offered treatment options such as lumpectomy or postoperative breast irradiation. “All of these women don’t need all of these treatment options, but a certain percentage do, and they shouldn’t be shortchanged because of age-only criteria,” said Dr. Muss.

Dr. Muss stressed that proper doctor-patient conversations about health-assessment and treatment goals are key to achieving optimal outcomes. “We need to analyze our elderly patients as individuals and be cognizant of the fact that age cannot be calculated as just a chronologic number. Rather, we need to consider the way an individual’s health is related to his age-related physiologic and functional status,” commented Dr. Muss.

Quality-of-life Measures

Put simply, Dr. Muss contends that knowing what a patient is capable of doing—basic functional status—is the first step in evaluating proper quality-of-life measures. “Can the patient drive, cook, dress herself; is the family structure solid? A lot of oncologists have not learned how to do simple assessments of the elderly,” said Dr. Muss.

Put simply, Dr. Muss contends that knowing what a patient is capable of doing—basic functional status—is the first step in evaluating proper quality-of-life measures. “Can the patient drive, cook, dress herself; is the family structure solid? A lot of oncologists have not learned how to do simple assessments of the elderly,” said Dr. Muss.

He suggests implementing one of the various comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) instruments that are currently available. “A geriatric assessment tool helps the physician determine what therapies the patient will be able to undergo and benefit from,” said Dr. Muss.

Assessment instruments are also important tools in quality-of-life issues such as pain management. “Opioid fear among geriatric patients is another problematic issue, said Dr. Muss, adding, “Unwarranted alarm of addiction can lead patients to reject or neglect to adhere to opioid regimens.”

Dr. Muss said that any pain assessment must be tailored to the way in which age affects how a body processes drugs. Changes in metabolic rates and blood flow affect how geriatric patients absorb and eliminate opioids. “Also, because elderly patients usually take several medications, there is an increasing risk of toxicity and adverse drug interactions when managing their pain,” said Dr. Muss.

Proper symptom management should also include the assessment of psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and delirium. “We’ve developed effective tools to determine whether elderly patients are experiencing psychological problems, and we have good medications to treat these problems. It’s important to realize that older patients have different life expectations and concerns than patients who are still working and rearing a family. As doctors, we can learn a lot from our elderly patients as we treat them; we just need to listen.”

A Career Change

Dr. Muss said that he entered the field of geriatric oncology about 15 years ago, largely due to a request by pioneering geriatrician William Hazzard, MD, then department chair at Wake Forest University. “Dr. Hazzard asked me to work with a medical resident on a retrospective review of what was one of the first detailed breast cancer databases, comparing outcomes of women with metastatic breast cancer who received older agents vs outcomes using modern chemotherapy regimens, by age,” said Dr. Muss.

Early skepticism about the worth of the project was met with career-changing results. “Fortunately, we had data from trials that did not have an upper age limit, and we compared outcomes of older women with advanced disease to those of younger patients with breast cancer. To our pleasant surprise, there was no difference in response rates among the different age groups,” explained Dr. Muss.

While preparing a subsequent manuscript that was accepted for publication in JAMA, Dr. Muss said that he became aware of how interesting and relevant the experience had been. “I was hooked. After a career as a breast cancer specialist I had reinvented myself as a geriatric oncologist.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Muss reported no potential conflicts of interest.