About 10 years ago, on a flight to Detroit, while returning from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, I had a conversation with Lori Pierce, MD, FASTRO, FASCO, radiation oncologist at the University of Michigan, who went on to become ASCO President for the 2020–2021 term. I recall inviting her to be a guest speaker at our Lebanese Society of Medical Oncology Annual Meeting. She was worried about safety but also had heard that “Beirut is like New York.” I remember joking with her and saying: some people also say “New York is like Beirut!”

On a recent Sunday morning, away from my clinical work and ordinary weekday interruptions, I had planned to finalize my talk for the upcoming Advanced Breast Cancer International Consensus Guidelines conference. However, that time without distractions was not to last. Living in Lebanon, a country that is now in severe political, economic, and financial crisis due to political instability in the Middle East and corruption closer to home, means that we live in survival mode.

Our own hospital is paying for bus services to transport doctors, nurses, and hospital staff from their homes to the hospital and back because they cannot afford the high cost of gasoline.— Nagi S. El Saghir, MD, FACP, FASCO

Tweet this quote

Routine Outages and Shortages

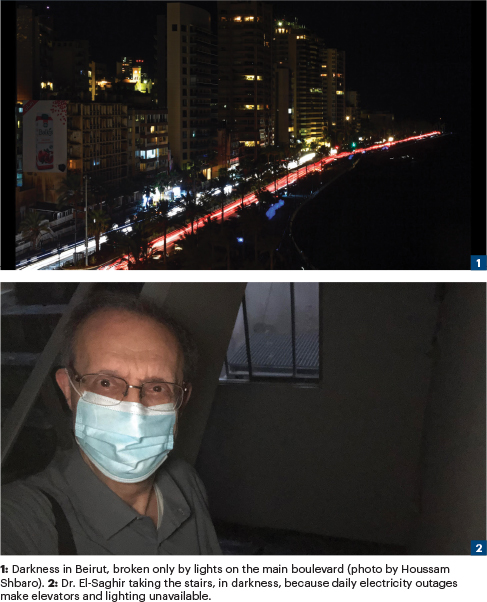

At home, when our government-dependent electricity goes off, we turn on our building generator. Our building generator is meant to be used as backup in the event of emergency or power outage, not for use continuously between 21 and 23 hours per day. To conserve power, we turn off the generator for 2 hours in the morning, 2 hours in the afternoon, and 6 hours at night.

At 11:00 AM on this particular day, before the elevator was shut down, I went to my office to work on my presentation. Returning home later that day, I noticed that my car was nearly out of gas. I drove by four or five gas stations, all of them closed because there is a gas shortage in the country. People are spending an average of 3 hours in gas station queues, waiting to fill up their cars.

In the evening, a patient of mine called to tell me about a gas station that was open, and I immediately headed there. At night, the streets of Beirut are dark and chaotic—90% of traffic lights are out of order, tunnels are dark, cars have their high beams on, and pedestrians need to cross the streets cautiously, as drivers do not always respect the right of way. The 30-minute drive to the gas station was exhausting, and driving back home was yet another nightmare experience.

Sleepless Nights

Like most residents of Lebanon, especially those of us who live in the cities, I have spent hot summer nights sleepless because of the daily power outages. It is not easy to perform your daily work, particularly medical and surgical work, when you do not get enough sleep.

Many nights I have had to sleep under a window or on my balcony to get a light breeze, or pay to stay in an air-conditioned hotel room. One colleague told me he regularly woke at 4:30 AM, another at 3:00 AM, and neither could get back to sleep because of the oppressive heat compounded by the lack of electricity for air conditioning. Many of my friends have briefly escaped to the mountains, where it is cooler, but they could not do so for long because of the gas shortages.

Impact on Health Care

Workforces everywhere in Lebanon have been affected by the devaluation of Lebanese currency (the Lebanese pound). The gas shortages have resulted in higher prices and black market sales. Our own hospital is paying for bus services to transport doctors, nurses, and hospital staff from their homes to the hospital and back because they cannot afford the high cost of gasoline.

Hospital supplies and medications have also started to be scarce and often go missing; if they are available, their prices have risen to levels prohibitive to patients and even insurance companies. Our hospital and others were able to partially manage with inventory and reserves, but it eventually got to the point of having to buy new materials at higher prices.

Patients go from pharmacy to pharmacy, city to city, in search of their medications, whether they need an antiestrogen like tamoxifen, a beta blocker, an antiarrhythmic, an oral anticoagulant, or a hypoglycemic agent. Worse still is that even basic vaccines for children have become unavailable or difficult to find, and tens of thousands of children are not getting their vaccines on schedule.

The central bank of Lebanon has ceased to sponsor medications and supplies because it says it has no more monetary cash reserves. Commercial pharmaceutical dealers have stopped importing medicines and supplies because of scarce central bank and government subsidies, resulting in great shortages of needed resources. It is difficult to imagine what our patients with cancer are going through under such trying circumstances. They are not only dealing with their cancer diagnosis, but they are often suffering the additional anxiety of not being able to get treatment.

New Government Faces Ongoing Crises

Lebanon’s new government, although composed of expert professionals, was formed by some of the same political powers that led the country to where it is now. The new leaders are hoping to slow down the economic disasters, but international financial analysts are predicting a worsening of the economy because of political unrest, with no recovery in sight for the next 15 to 20 years.

People are anxious and uncertain about the future, fearing the impact that the devaluation of Lebanese currency will have on their savings. The Lebanese authorities say they are overwhelmed with applications for new passports from people seeking to migrate out of the country.

The ongoing economic crisis and deteriorating living conditions, in the absence of solid plans for reforms and hope for recovery, have caused a severe “brain drain” in Lebanon. Thousands of physicians, nurses, and skilled health-care workers have left the country, moving to the United States, France, Canada, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and many other countries. This huge migration is also being seen in other groups of professionals, including engineers, teachers, businesspeople, and entertainers. Countries accepting these people are providing a better quality of life and allowing them to prosper without having invested in their education.

More Support and Supplies Needed

Lebanon is in turmoil, and its people, including patients with cancer, are suffering as a result. People who can do so are managing, but not easily. Those who can afford to are buying their medicines outside of the country or having their relatives and friends bring them from overseas. Fortunately, the Board of Trustees of the American University of Beirut, among many international donors, Lebanese diaspora, and alumni of Lebanese universities, have provided hospitals with partial support, supplies, and medications. However, a lot more is needed—and will be needed for a long time to come.

Dr. El Saghir is Head of the Division of Hematology Oncology, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Lebanon. He is also Past Chair of the ASCO International Affairs Committee. Follow him on Twitter @NagiSaghir.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. El Saghir has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Lilly, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; has received institutional research funding from Roche; and has been reimbursed for travel, accommodations, or other expenses by MSD Oncology and Roche.