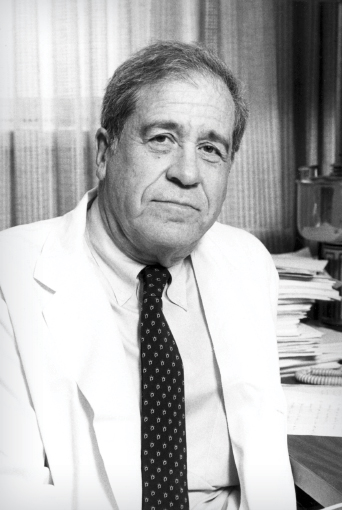

American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn coined the term “paradigm shift” to connote a fundamental change in the basic concepts and practices of a standard scientific discipline. They are few and far between. To convince the entrenched oncologic surgery community in the 1960s and 1970s that the revered “more-is-better” radical Halsted mastectomy—a treatment that was standard of care for 75 years—should be replaced by breast-conserving therapy, with or without radiation, would be a paradigm shift that would alter the scientific approach to breast cancer treatment and spare millions of women from disfiguring surgery. It would also take a tooth-and-nail struggle from a brave and determined surgeon-researcher. That surgeon was Bernard Fisher, MD. He died on October 16, 2019, at the age of 101.

A Mentor Helps Shape a Great Career

Dr. Fisher was born in Pittsburgh on August 23, 1918, the son of Anna and Reuben Fisher. Dr. Fisher’s early school career was marked with a prodigious love and talent for science. He graduated from Taylor Allderdice High School in 1936 and attended the University of Pittsburgh Medical School, earning his medical degree in 1943 and staying on to complete his surgical residency.

Around this time, his great-uncle, a physiologist and surgeon, moved to the University of Pittsburgh to create a lab to develop an adrenal cortical extract for the treatment of Addison’s disease. “I got my first taste of lab work there, while I was a medical student. They would get big containers of adrenal glands from the slaughterhouse, and one of my jobs was to remove the medullas from those glands,” Dr. Fisher said in an interview from 2008.

It was during this formative time during his surgical residency that the young doctor began questioning the rationale for many of the operations he was performing, spurring a desire for a greater understanding of the biology of the diseases he was treating. Questioning the status quo would be a lifelong trait.

From 1950 to 1952, Dr. Fisher was a fellow in experimental surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, where he worked with his mentor, I.S. Ravdin, MD, Chair of Surgery at Penn. He convinced Dr. Ravdin to offer him a research position, which he did. When his tenure at Penn ended, Dr. Fisher returned to the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, where he created the Laboratory of Surgical Research.

“I had only a small stipend to live on, but I was happy. It was my lab, and I was given the opportunity to do as I pleased,” he noted. “At that time, I had no interest in breast cancer.” Thus began a pivotal period in Dr. Fisher’s maturation as a surgeon-researcher.

Transformative Changes in Breast Cancer Treatment

In the spring of 1957, career-changing opportunity knocked, and once again it was presented by his mentor, Dr. Ravdin. He invited Dr. Fisher to join 22 other surgeons at a National Institutes of Health meeting to establish the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Early on during this seminal period with the NSABP, Dr. Fisher became fascinated by “the mystery of metastasis and the brand new concept of the clinical trial.” His life’s work began taking shape as he dove headlong into breast cancer research and clinical trial development.

In 1967, Dr. Fisher became Chairman of the NSABP, and over the succeeding decades, his groundbreaking research and clinical trial leadership would result in transformative changes in the treatment of breast cancer. Despite solid evidence that lumpectomy followed by radiation was equivalent to radical mastectomy, Dr. Fisher described the widespread resistance to his approach as “extensive and often unpleasant.” In the end, Dr. Fisher prevailed, and his work also won over the emerging women’s health movement, becoming a political as well as a medical issue.

A Fighter Until the End

After publication of his pioneering research, it was publicly revealed that an NSABP investigator had taken liberties with clinical trial data, causing an uproar that led to a challenging period in Dr. Fisher’s life and work. Once again, he’d have to fight the establishment, and once again, he ultimately won and was cleared of any charges of data misconduct.

Exonerated by the federal Office of Research Integrity, he resumed his position at the NSABP until 1994. Dr. Fisher was heralded as one of the most important cancer researchers of modern times. He received far too many awards to begin listing, but it is his courageous and brilliant work that changed the course of breast cancer treatment that will be his lasting legacy.

His seminal work has saved countless patient lives and has had an immeasurable effect in allaying suffering. I have lost a mentor, colleague, and friend, and the field of oncology has lost its noblest protagonist.— Norman Wolmark, MD, FACS

Tweet this quote

As word of Dr. Fisher’s death spread, tributes from around the world amassed. But it is fitting to share one from another great breast cancer researcher who called Dr. Fisher the single most important influence on his career: Norman Wolmark, MD, FACS, Professor of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, who succeeded Dr. Fisher as Chairman and Principal Investigator for the NSABP. Dr. Wolmark said:

All of oncology owes an enormous debt of gratitude to the contributions of Bernard Fisher. He instilled in us the passion for the randomized prospective clinical trial as a vehicle to define optimum therapy in the treatment of breast cancer and other solid tumors applying the scientific method. He delivered us from the age of tyranny, when a single individual could dictate the therapy of a particular disease based on his own biased retrospective experience. In the process, Bernard Fisher revolutionized our understanding of the biology of breast cancer. His seminal work has saved countless patient lives and has had an immeasurable effect in allaying suffering. I have lost a mentor, colleague, and friend, and the field of oncology has lost its noblest protagonist. ■