Paul Neiman, MD, PhD ©Fred Hutch file photo

PAUL NEIMAN, MD, PhD, a founding member of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Fred Hutch), transplant physician, and cancer biologist, died on October 11 of complications from pancreatic cancer. He was 78.

Dr. Neiman was also one of the founders and leaders of the Basic Sciences Division, one of Fred Hutch’s five scientific divisions, as well as the division that would later became the Human Biology Division. He served as Director of Basic Sciences from 1983 to 1995. He retired from Fred Hutch in 2010 but continued to work behind the scenes to secure new sources of funding for the Basic Sciences Division.

He was well known in the scientific community for his fundamental research on the interplay between viruses and cancer cells, making key discoveries about the nature of retroviruses. But at Fred Hutch, he was perhaps better known for making connections and building bridges, said many of his colleagues.

“He loved to think about connections between people and which connections will work and make things happen,” said Robert Eisenman, PhD, a molecular biologist who was one of Dr. Neiman’s first recruits to join the newly formed Fred Hutch, in an earlier interview. “If it weren’t for him, the face of the Hutch would be really different now.”

Dr. Eisenman’s colleague and former postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Neiman’s lab, Fred Hutch virologist Maxine Linial, PhD, agreed. “I think there wouldn’t be a Hutch as a first-class research institute if it wasn’t for Paul Neiman,” she said in a 2015 interview with the Fred Hutch News Service.

A Love of Research

DR. NEIMAN grew up in Seattle, as did his wife of 56 years, Carol. He went to Seattle’s Franklin High School and then to the University of Washington for both college and medical school.

Dr. Neiman caught the research bug as a medical student in the early 1960s and quickly came to see how biologic research and medicine can complement each other. That love of research led him to study leukemia at the National Cancer Institute for a few years after receiving his medical degree in 1964. He joined Dr. E. Donnall Thomas’ Seattle transplant team in 1968, when Dr. Thomas still ran a small unit in what was then Providence Hospital. Dr. Neiman also started his research laboratory to study a unique retrovirus called the Rous sarcoma virus, which causes cancer in chickens. He and his colleagues used that virus as a route to better understand the molecules that drive all tumor formation.

When Fred Hutch opened its doors in 1975, Dr. Neiman was part of the original small group of faculty and helped shape much of the cancer center’s research efforts, including directing scientific programs from 1980 to 1983.

Dr. Neiman’s own work is one of many examples of how fundamental research has led to new, unexpected understandings of human health. When he first launched his research laboratory in the early 1970s, the scientific community largely believed human cancer was caused by retroviruses, just as the sarcoma Dr. Neiman studied in chickens is triggered by the Rous virus.

Although that theory later proved false, Dr. Neiman and his colleagues’ work on Rous and similar viruses shed light on the workings of both retroviruses and oncogenes. Many scientists in the 1960s and 1970s made vital contributions to understanding these at-the-time mysterious viruses; Dr. Neiman demonstrated the presence of foreign DNA from retroviruses stitched into the genomes of infected cells, largely settling what was then a controversial issue. That finding—published in 1972, years before HIV was discovered—was a critical piece in understanding how retroviruses work.

Dr. Neiman’s work also led to further studies in his laboratory that elucidated how certain oncogenes drive cancer cells to act differently from healthy cells. He showed that programmed cell death plays a role in tumors spurred by oncogenes, and in one of his last papers, he demonstrated that the Myc oncogene causes genomic damage and instability in cancer cells.

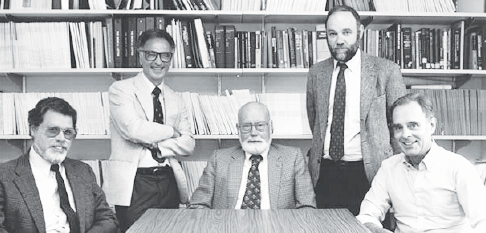

Fred Hutch’s original bone marrow transplant team, led by the late Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, in 1989. From left: Dr. Neiman, Dr. Alex Fefer, Dr. Thomas, Dr. C. Dean Buckner, and Dr. Rainer Storb. Photo credit: Fred Hutch’s Arnold Library archive

Training Other Physician-Scientists

DR. NEIMAN helped further the careers of many other physicians who aspired to branch out into research. Just as he was given a chance to try his hand at the bench without the traditional scientific training of a PhD, so too he helped other medical students and residents gain research experience at the Hutch.

“Paul was pivotal in my career,” said Craig B. Thompson, MD, a medical oncologist who is now President and Chief Executive Officer of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Dr. Thompson trained with Dr. Neiman as well as with Fred Hutch molecular biologist and special advisor to the director’s office Mark Groudine, MD, PhD.

Dr. Groudine also benefited from Dr. Neiman’s mentorship. Dr. Groudine had completed both an MD and a PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and a year of postdoctoral work with the late Harold Weintraub, MD, PhD, at Princeton University when he came to Seattle to do a residency at the University of Washington. “Paul was a wonderful mentor who was instrumental in shaping my career,” Dr. Groudine said.

Why Cancer Centers Need Basic Science

DR. NEIMAN saw the value of conducting fundamental research in biology at Fred Hutch, where basic scientists mingled with their clinical colleagues for close collaborations that would ultimately lead to better treatments for patients with cancer. Soon after the inception of Fred Hutch, Dr. Neiman and his colleagues realized that basic biologic research needed to be expanded and formalized. In 1981, Fred Hutch formed the Basic Sciences Division.

“Paul was known for being as dedicated to his patients as he was to the fundamental research he championed,” said Fred Hutch President and Director, Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD. “He recognized that having great basic science at a cancer research center was essential to future advances for patients.”

“Treating patients was clearly of immense importance, but Paul felt basic research was an investment in the future of medicine,” Dr. Eisenman said. ■