Management of patients with cancer who have fever and a low neutrophil count is one of the most common scenarios oncologists face today. “Physicians have to be keenly aware of the infection risks, diagnostic methods, and microbial therapies required for managing febrile neutropenic patients because they’re highly vulnerable to rapidly progressive, severe infections in the absence of neutrophils,” said Alison G. Freifeld, MD, Professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, in an interview with The ASCO Post.

Eric J. Bow, MD, Professor in the Departments of Medical Microbiology and Internal Medicine, and Director of the Infection Control Services, CancerCare Manitoba, Winnipeg, agreed, noting, “Patients with a neutropenic fever syndrome who are untreated or improperly treated have a high risk of dying, with a median survival on the order of 72 hours.” Yet, treatment—starting with appropriate antibiotic selection—is not always straightforward, given factors such as patient diversity, an array of antibiotic options, and emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Practice Guidelines

Evidence-based practice guidelines, such as those of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)1 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),2 offer helpful information and algorithms when it comes to antibiotic therapy for febrile neutropenic patients. (ASCO guidelines for managing febrile neutropenia in the outpatient with cancer are currently being written, and publication is anticipated this year.)

Evidence-based practice guidelines, such as those of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)1 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),2 offer helpful information and algorithms when it comes to antibiotic therapy for febrile neutropenic patients. (ASCO guidelines for managing febrile neutropenia in the outpatient with cancer are currently being written, and publication is anticipated this year.)

“An algorithmic approach to febrile neutropenia, infection prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment helps to guide clinical management,” Dr. Freifeld noted. “It’s not intended to replace clinical judgment, but in an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance and an ever-widening array of pathogens, we need some structure in our initial management approaches.”

It is also noteworthy that guidelines have become less dogmatic and more flexible over time, according to Dr. Bow. “They allow physicians to use their judgment a little bit more and also to be confident that in so doing, they will be complying with standards of practice,” he explained. This approach not only accommodates local circumstances, such as antibiotic availability and prevailing resistance patterns, but also addresses liability concerns.

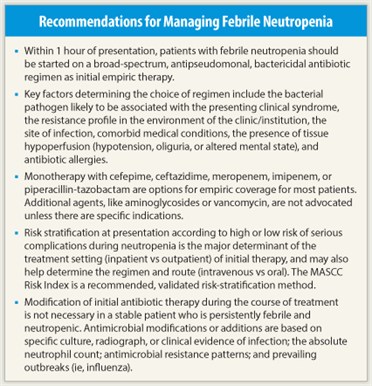

The guidelines concur that speed is of the essence when treating febrile neutropenia: Patients should be started on initial empiric antibacterial therapy within 1 hour of presentation to a triage facility. As Dr. Bow noted, using the standardized emergency department triage assessment system,3 febrile neutropenic patients with cancer can be recognized and classified in a manner similar to that for patients with acute ST-wave myocardial infarction or acute stroke for timely management. During those first few minutes, “full clinical assessments, blood cultures, and appropriate blood work all need to be done. That’s difficult but achievable,” he said.

The guidelines concur that speed is of the essence when treating febrile neutropenia: Patients should be started on initial empiric antibacterial therapy within 1 hour of presentation to a triage facility. As Dr. Bow noted, using the standardized emergency department triage assessment system,3 febrile neutropenic patients with cancer can be recognized and classified in a manner similar to that for patients with acute ST-wave myocardial infarction or acute stroke for timely management. During those first few minutes, “full clinical assessments, blood cultures, and appropriate blood work all need to be done. That’s difficult but achievable,” he said.

Over the past 2 decades, the initial empiric antibacterial approach for fever and neutropenia have actually been simplified. In the 1970s and 1980s, multidrug antibiotic regimens were often prescribed, including an antipseudomonal cephalosporin or penicillin plus an aminoglycoside and vancomycin. Current guidelines recommend monotherapy with a potent broad-spectrum antipseudomonal agent such as intravenous cefepime, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam.1,2 Universal coverage with vancomycin (or similar anti–gram-positive agents) and aminoglycosides has been found to be generally unnecessary in clinical trials, but these agents may be reserved for specific situations (see below).

Patient Risk and Initial Therapy

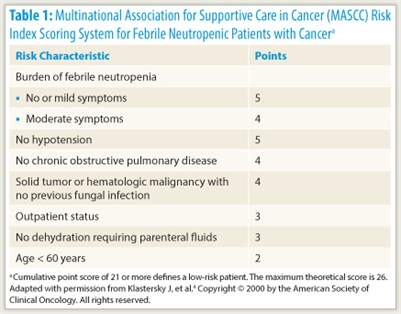

A patient’s risk of serious medical complications during the course of neutropenia is an important determinant of the route (intravenous vs oral) and treatment setting (inpatient vs outpatient) of empiric antibiotic therapy at the outset. Risk can be assessed from individual factors, such as age, underlying cancer, treatment regimen intensity, medical comorbidities (including dehydration or hypotension), and evidence of sepsis, or using the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Risk Index, on which a score of less than 21 indicates high risk (Table 1).4

A patient’s risk of serious medical complications during the course of neutropenia is an important determinant of the route (intravenous vs oral) and treatment setting (inpatient vs outpatient) of empiric antibiotic therapy at the outset. Risk can be assessed from individual factors, such as age, underlying cancer, treatment regimen intensity, medical comorbidities (including dehydration or hypotension), and evidence of sepsis, or using the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Risk Index, on which a score of less than 21 indicates high risk (Table 1).4

“The MASCC Risk Index score has very robust evidence for its ability to distinguish between high- and low-risk patients. It is probably the most highly validated tool,” Dr. Freifeld commented.

High-risk patients are typically those undergoing induction for acute myeloid leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and are generally treated as inpatients with intravenous antibiotic therapy. Guideline-recommended therapy includes any of several broad-spectrum beta-lactam monotherapy options: imipenem (with cilastatin), meropenem, or another carbapenem; piperacillin (with tazobactam), ceftazidime, or cefepime. Guidelines also list as an option intravenous combination therapy, such as an aminoglycoside plus an antipseudomonal beta-lactam antibiotic.

“Although numerous well-performed clinical trials have been conducted over several decades, no single therapeutic regimen for initial treatment of febrile neutropenia has emerged as clearly superior to others,” Dr. Freifeld noted. “All effective regimens, both monotherapies and combination therapies, share certain features that are essential. Bactericidal activity in the absence of white cells is extremely important; this is provided most effectively by cephalosporins and penicillins. And antipseudomonal coverage also remains a linchpin of the initial regimen,” she added.

“Whilst each of these regimens may have a little bit of a niche advantage, one over the other, for specific reasons, by and large, they all perform fairly well, predictably, and safely,” Dr. Bow agreed. “The guidelines are intended to give physicians an understanding of the principles upon which they could choose any number of products to achieve the same outcome.”

Low-risk patients are usually those with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy regimens that result in brief durations of neutropenia. They may present with evidence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, possibly with an infection focus, but without evidence of hypoperfusion or organ dysfunction. These patients may be treated as inpatients with the above intravenous therapy options but may also be eligible for oral combination therapy, namely, ciprofloxacin plus amoxicillin with clavulanate, if they are deemed stable and able to tolerate oral medications.

Outpatient management is a particularly attractive prospect for some low-risk patients, although eligibility depends on their ability to tolerate an oral regimen, their access to a telephone and transportation, and the availability of a caregiver. Because there is less intensive monitoring outside the hospital, the potential for complications and drug safety become especially important considerations, noted Brahm H. Segal, MD, Professor of Medicine at the University of Buffalo School of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in New York. Yet, when feasible, outpatient therapy has the advantages of greater patient convenience and lower cost, he added.

Outpatient management is a particularly attractive prospect for some low-risk patients, although eligibility depends on their ability to tolerate an oral regimen, their access to a telephone and transportation, and the availability of a caregiver. Because there is less intensive monitoring outside the hospital, the potential for complications and drug safety become especially important considerations, noted Brahm H. Segal, MD, Professor of Medicine at the University of Buffalo School of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in New York. Yet, when feasible, outpatient therapy has the advantages of greater patient convenience and lower cost, he added.

Perhaps equally important in selecting an initial antibiotic therapy are certain drugs that are not recommended for routine use in this setting. “The use of antibiotics with extended activity against gram-positive organisms, like vancomycin and daptomycin [Cubicin], is generally not required. One should not prescribe these antimicrobials unless there’s a specific indication as outlined in the guidelines, so as to avoid overuse, due mainly to our concerns about resistance among the gram-positive organisms, primarily Staphylococcus aureus,” Dr. Freifeld advised.

Situations in which guidelines recommend vancomycin are those in which there is a high local prevalence of methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) infections or in which the febrile neutropenia is more likely due to MRSA, such as central venous catheter–related infections, and skin and soft-tissue infections. Importantly, guidelines recommend discontinuing vancomycin if, after 48 to 72 hours, cultures do not show any pathogen warranting this antibiotic. “Such a strategy can prevent toxicity and selection for resistant bacteria,” Dr. Bow commented.

Additional Considerations

A variety of other factors are helpful in selecting among the above options for initial antibiotic therapy. These include the drug interactions and adverse effects of a given antibiotic. “Antibacterial agents are generally well tolerated,” Dr. Segal noted. Overall, they have known adverse effects that include nausea, rash, and the potential for allergic reactions and predisposition to Clostridium difficile colitis. “However, there are some that have specific toxicities—for example, aminoglycosides as a class have renal toxicity.”

A variety of other factors are helpful in selecting among the above options for initial antibiotic therapy. These include the drug interactions and adverse effects of a given antibiotic. “Antibacterial agents are generally well tolerated,” Dr. Segal noted. Overall, they have known adverse effects that include nausea, rash, and the potential for allergic reactions and predisposition to Clostridium difficile colitis. “However, there are some that have specific toxicities—for example, aminoglycosides as a class have renal toxicity.”

In selecting an initial regimen, clinicians must also now consider resistance issues, including MRSA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, fluoroquinolone resistance among gram-negative bacilli, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase– and carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacilli—all of which have the potential to seriously reduce the effectiveness of initial empiric antibiotic therapy, Dr. Bow noted.

Prior prophylaxis can limit options for initial antibiotic therapy as well. For example, patients with febrile neutropenia who have been receiving fluoroquinolone prophylaxis are not candidates for the oral antibiotic combination therapy above (ie, ciprofloxacin plus amoxicillin with clavulanate).

Finally, the site of known or suspected infection may help guide antibiotic choice, as well as suggest the need for additional coverage. For example, “if the patient has new abdominal pain and signs and symptoms suggesting an abdominal process, then I’d chose a regimen with greater anaerobic coverage, such as imipenem or meropenem,” Dr. Freifeld explained.

On the other hand, she continued, “if they have an infiltrate on chest x-ray and clinical evidence of pneumonia, they would require a multidrug regimen for health care–acquired pneumonia. That would include vancomycin and a macrolide or fluoroquinolone, as well as a beta-lactam drug.”

Similarly, guidelines recommend that clinicians consider viral testing and adding antiviral therapy targeting herpes simplex viruses for patients with suspicious oral lesions, and antifungal therapy for those with persistent neutropenic fever syndrome despite up to 5 days of broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy.

Modifying Initial Therapy

“Further modifications to initial antibiotic regimens should be based on clinical and microbiologic findings, rather than on the persistent presence of fever alone. In other words, we always emphasize this: No changes in the initial antibiotic regimen are required in stable patients who have persistent fever,” Dr. Freifeld said. “The only exception to that is the use of empiric antifungal therapy; typically, patients who continue to be febrile beyond 96 hours of empiric antibacterial therapy are candidates for antifungal therapy.”

“Further modifications to initial antibiotic regimens should be based on clinical and microbiologic findings, rather than on the persistent presence of fever alone. In other words, we always emphasize this: No changes in the initial antibiotic regimen are required in stable patients who have persistent fever,” Dr. Freifeld said. “The only exception to that is the use of empiric antifungal therapy; typically, patients who continue to be febrile beyond 96 hours of empiric antibacterial therapy are candidates for antifungal therapy.”

Dr. Segal added, “The rationale for empiric antifungal therapy is to treat a possible occult fungal infection that may be unrecognized by physical exam and routine cultures. In addition, a broad-spectrum antifungal agent (eg, a mold-active azole or echinocandin) is commonly used as prophylaxis in patients with prolonged neutropenia at high risk for invasive fungal diseases, such as those receiving induction or reinduction regimens for acute myeloid leukemia. In patients receiving prophylaxis with a broad-spectrum antifungal agent, modifying the antifungal regimen solely based on persistent fever is of unclear value. Some centers perform surveillance testing for early fungal disease (eg, serial serum galactomannan and/or beta-glucan testing) in high-risk patients, to guide decisions about when to begin or modify the antifungal regimen.” ■

Disclosure: Drs. Freifeld, Bow, and Segal reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al: Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52(4):e56-e93, 2011.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections. Version 2.2011. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf. Accessed Feb. 18, 2012.

3. Bullard MJ, Unger B, Spence J, et al: Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) adult guidelines. Can J Emerg Med 10:136-151, 2008.

4. Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al: The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Risk Index: A multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 18:3038-3051, 2000.