“At Microphone 1” is an occasional column written by Steven E. Vogl, MD, of the Bronx, New York. When he is not in his clinic, he can generally be found at major oncology meetings and often at the microphone, where he stands ready with critical questions for presenters of new data. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author. If you would like to share your opinion on this or another topic, please write to editor@ASCOPost.com.

Steven E. Vogl, MD

At the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting, Qian Shi, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, presented a combined individual patient analysis of six studies conducted around the world, looking at 6 vs 3 months of adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive colon cancer.1 Despite enrolling almost 13,000 subjects, the results remain equivocal.

Overall, the analysis failed to exclude a 5% chance that longer therapy improves 3-year disease-free survival by a relative increase of 12%. If the 6-month course had a 3-year disease-free survival of 75.5% (the actual observation in the 6-trial meta-analysis called “IDEA”), the goal was to exclude with 95% confidence that reducing therapy to a 3-month course decreased the 3-year disease-free survival to 72.6%. In the landmark MOSAIC trial that established FOLFOX for 6 months as the standard adjuvant therapy for resected node-positive colon cancer, 3-year disease-free survival improved by 6.9% if 6 months of oxaliplatin was added to 6 months of an every-2-week program of leucovorin plus 44-hour infusion of fluorouracil (5-FU). The six studies asked how much of this gain is lost if only 3 months of oxaliplatin are given and the fluoropyrimidine (5-FU or its oral prodrug capecitabine) course also is reduced to 3 months.

In his presentation of the French contribution to the IDEA meta-analysis (called “IDEA-France”), Thierry Andre, MD, of the University Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris, estimated that surgery cures 50% to 60% of node-positive colon cancer cases, LV5FU2 (leucovorin plus the 44-hour 5-FU infusion) cures another 12% to 15%, and the addition of oxaliplatin (making FOLFOX) cures another 6%.3 In IDEA-France, 90% of patients received FOLFOX. This trial showed that a second 3 months of therapy improved 3-year disease-free survival by 4% (2% for patients with T1–3N1 disease and 8% for higher-risk patients with T4 or N2 disease).

Benefit vs Toxicity: The Real Question

ALTHOUGH THE duration of adjuvant therapy was the focus of these studies, it became clear from Dr. Shi’s presentation that the real question was whether the added long-term toxicity of the second 3 months of therapy is justified by the benefit. The long-term toxicity is entirely neurotoxicity from oxaliplatin. At 48 months after completion of 6 months of FOLFOX treatment, 15.4% of patients still had neuropathy; 3.5% had grade 2 or 3 neuropathy interfering with daily function.4

The question asked in each of these six studies should have been whether oxaliplatin therapy could be safely stopped after 3 months. Had the only variable been the duration of oxaliplatin, we would not now be having a discussion analyzing the results by which fluoropyrimidine was used. In previous adjuvant trials for which the choice of fluoropyrimidine was the main issue, capecitabine proved equal to or slightly better than 5-FU/leucovorin.

“Fairness and ethics would have been better served by obtaining patient consent at the 3-month point, when he or she has experienced the toxicities.”— Steven E. Vogl, MD

Tweet this quote

Focus on Tolerability

STRATIFICATION TO ensure comparable populations in the study arms was done before randomization in all six trials; therefore, treatment assignment was not balanced according to patient characteristics during and at the conclusion of the first 12 weeks of therapy, when the treatment arms diverged. We do not know how the 6-month patients did according to their dose, toxicities, treatment delays and modifications, performance status, and blood cell counts during and at the conclusion of the first 3 months of receiving FOLFOX or CAPOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin). By chance, the group assigned to 6 months could have had more mucosal, hematologic, or neurologic toxicity in the first 3 months than the group assigned to 3 months of chemotherapy. Some of this toxicity in the first 3 months (especially neurotoxicity) may have led to premature cessation of all chemotherapy short of the 6-month point.

To ensure comparability of the assigned groups and that all patients completed the first 3 months of therapy, randomization should have occurred after the completion of 3 months of therapy. Treatment assignment should have been stratified by patient condition, prior toxicity, and current characteristics (performance) as well as restricted according to organ function, blood cell counts, neurologic function, and willingness of the patient to proceed with treatment at the time treatment arms diverge.

Fairness and ethics would have been better served by obtaining patient consent at the 3-month point, when he or she has experienced the toxicities—skin and mucosal for 5-FU or capecitabine and cold intolerance, infusional pain, and sensory neuropathy for oxaliplatin. The consent at this point would have been better informed, and the study would have been more likely to answer the question by excluding those who already had stopped chemotherapy or, if toxicity was already severe, would have been likely soon to refuse to proceed with more chemotherapy.

“Probably few patients would risk significant rates of severe neuropathy for an absolute 5-year survival benefit under 1%, and many would risk moderate neuropathy for a benefit over 3%.”— Steven E. Vogl, MD

Tweet this quote

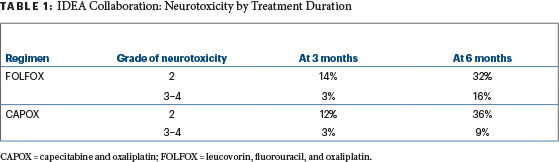

It makes sense to stratify by events during the first 3 months of therapy and to exclude some patients based on these events. Those who have much more toxicity during the first 3 months likely will have more toxicity in the second 3 months—as well as more dose reductions—and more often will fail to complete therapy. They may prove to gain no benefit at all from trying to complete 6 months. After just 3 months of therapy, 3% of both FOLFOX and CAPOX patients already had grade 3 or 4 neuropathy (Table 1).

Table 1

Many would argue these patients should stop neurotoxic agents permanently and not be randomized—14% of FOLFOX patients and 12% of CAPOX patients already had grade 2 neuropathy after 3 months. Cautious investigators also would exclude these patients with grade 2 neuropathy from further neurotoxic oxaliplatin as well. In her final slide at the ASCO 2017 Plenary Session, Dr. Shi herself suggested the duration of therapy for higher-risk patients should be determined in part by tolerability of the chemotherapy during the first 3 months.

Too Late to Compare Toxicities?

IT MAY NOT be too late to compare toxicities in the first 3 months for both groups to assure both groups were comparable at the point the treatments diverged. Unfortunately, the SCOT trial stopped collecting toxicity data after the first 617 patients were enrolled.5 The other five trials, only two of which have been presented separately at medical meetings, may have these data. Disease-free and overall survival also should be evaluated according to toxicity during the first 3 months of therapy. It may be that those patients with grade 2 or worse neuropathy in the first 3 months obtained no benefit from an attempt to prolong therapy. This information would be very helpful in counseling already numb patients considering whether to endure 3 more months of progessively more toxic therapy.

The analyses of progression-free and overall survival should be redone to exclude patients in both groups who stopped therapy before the 3-month point. This step would eliminate the early noncompliers and early deaths, which would dilute any apparent benefit from proceeding beyond 3 months of FOLFOX or CAPOX.

If the six studies included in the IDEA collaboration had randomized after 3 months (thus excluding early stoppers from both groups) and excluded patients who clearly would fail to complete 6 months’ therapy because of already existing severe peripheral neuropathy, the benefits of continuing treatment beyond 3 months might be more obvious. They might even appear in the lower-risk group.

What Would Your Patient Want?

IT SEEMS LIKELY that a patient with good analytic skills would prefer to defer a decision on how long adjuvant chemotherapy should continue until the last possible moment, hoping the decision would be rendered easy. This could happen if poorly reversible toxicity (such as peripheral neuropathy) during initial therapy was severe or moderately severe, if there were early distant relapse, or if some intercurrent catastrophic event occurred. Similarly, if a patient adamantly wants to avoid a venous access device, and infusional pain in the accessed vein during the first few oxaliplatin administrations was nearly intolerable, the decision becomes easy. These events are fairly uncommon, however.

Even if the decision is not that easy, a patient would want to know in what ways his or her body’s reaction to the initial chemotherapy predicts his or her reaction to further therapy. Presumably, fluoropyrimidine doses have been adjusted to make reversible toxicities tolerable for patients, so continuing the fluoropyrimidine is not the issue, unless there is severe sensitivity to the fluoropyrimidine from dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. A patient would want information on how many patients with early (first 3 months) grade 1 or 2 peripheral neuropathy go on to develop grade 3 neuropathy with an additional 3 months of oxaliplatin, and how many actually stop treatment with oxaliplatin before reaching the 6-month point. The patient would ask whether the early onset of neuropathy from oxaliplatin predicts neuropathy that will last longer and remain more severe. And the patient would ask whether the absence of neuropathy after 3 months predicts a lower rate of severe and long-lasting neuropathy after 6 months of therapy are complete.

Most important, the patient would ask for the best estimate of the absolute benefit in terms of disease-free and overall survival from an additional 3 months of oxaliplatin. The benefit rate should now be based on the patient’s T and N stage, the number of resected nodes, as well as whether the primary tumor is right- or left-sided. In the near future, once the tests are standardized, the rate of benefit should also include risk estimates based on tumor genetics and gene expression.

Probably few patients would risk significant rates of severe neuropathy for an absolute benefit in 5-year overall survival under 1%, and many would risk moderate neuropathy for a benefit over 3%. Concert pianists and violinists, guitar virtuosi, and microvascular surgeons would likely require much greater benefits to risk career-ending toxicities to increase 5-year overall survival by percentages in the low single digits.

The IDEA collaborators owe it to our patients to analyze 6-month toxicity by the toxicity observed after 3 months. They should add tumor location (right vs left side of the colon) to the risk profiles of the tumors. They have already shown that 3 months of CAPOX is a pretty good adjuvant treatment for colon cancer that has not penetrated the colon serosa or invaded adjacent organs and is metastatic to no more than three nodes, although defects in study design and analysis have not nailed this down completely.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Vogl reported no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.

REFERENCES

1. Shi Q, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al: Prospective pooled analysis of six phase III trials investigating duration of adjuvant oxaliplatin-based therapy (3 vs 6 months) for patients with stage III colon cancer: The IDEA (International Duration Evaluation of Adjuvant chemotherapy) collaboration. 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract LBA1. Presented June 4, 2017.

2. André T, de Gramont A, Vernerey D, et al: Adjuvant fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in stage II to III colon cancer: Updated 10-year survival and outcomes according to BRAF mutation and mismatch repair status of the MOSAIC Study. J Clin Oncol 33:4176-4187, 2015.

3. Andre T, Bonnetain F, Mineur L, et al: Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer: Disease-free survival results of the three versus six months adjuvant IDEA France trial. 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3500. Presented June 5, 2017.

4. André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al: Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 27:3109-3116, 2009.

5. Iveson T, Kerr R, Saunders MP, et al: Final DFS results of the SCOT study: An international phase III randomised (1:1) non-inferiority trial comparing 3 versus 6 months of oxaliplatin based adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 3502. Presented June 5, 2017.