Health-care fraud is a long-standing problem in the United States, accounting for $75 billion in government expenses per year,1 while total spending on government health-care programs is over $1 trillion. Two decades ago, the Department of Justice increased its efforts to combat health-care fraud. This change was stimulated by the Federal False Claims Act, a 1986 legislation that allows qui tam relators (commonly termed “whistle-blowers”) to receive up to 30% of financial recoveries from successfully concluded False Claims Act investigations.

In 1996, the Federal Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Project was started by the Department of Health and Human Services. This project allocates funds and resources to fight federal health-care fraud and abuse, with much of the funding coming from financial recoveries obtained the prior year. The program reports annually to the public on the financial success of the recovery efforts.

Comprehensive Review

We comprehensively reviewed major recently completed health-care fraud cases (2006–2011), attempting to overcome limitations of prior published reviews of health-care fraud. These limitations included a focus on cases initiated by qui tam relators or on specific sectors (pharmaceuticals and Medicaid, in particular).1-4

All cases were recovered under the federal False Claims Act, the primary legislation used to investigate health care fraud and abuse. Data sources included Lexis/Nexis News (terms: “health care fraud,” “False Claims Act,” and “qui tam”), Taxpayers Against Fraud, and Department of Justice websites (2006–2011). Cases with recoveries over $5 million were included. Cases were evaluated as involving qui tam relators (whistle-blowers) or not, as relator cases historically account for 90% of all cases and 90% of all recoveries. 3

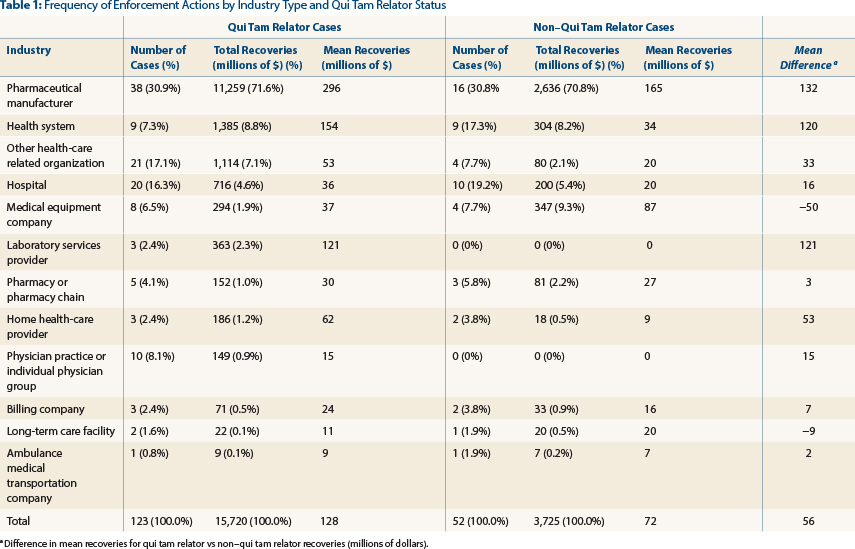

As illustrated in Table 1 (page 98), we found that between 2006 and 2011, 123 qui tam health-care fraud cases concluded, totaling $15.7 billion in recoveries (84% of the total recoveries). Pharmaceutical manufacturers accounted for 31% of these cases and $11.3 billion (72%) in recoveries. Health systems and related organizations accounted for 30 cases (24% of these cases), totaling $2.4 billion in recoveries (16% of recoveries). Hospitals accounted for 20 cases (16% of these cases), totaling $716 million in recoveries (5% of recoveries).

Fifty-two cases not involving qui tam relators (whistle-blowers) also concluded during these years, totaling $3.7 billion in federal recoveries (16% of the total recoveries). Pharmaceutical manufacturers accounted for 31% of these cases, and $2.6 billion (71% of non-qui-tam-related recoveries) in recoveries. Health systems and related organizations accounted for 13 cases (25% of these cases), totaling $384 million in recoveries (10% of recoveries). Hospitals accounted for 10 cases (20% of the cases), totaling $347 million in recoveries (5% of recoveries).

Important Implications

These findings provide the first comprehensive look at the huge financial fines paid in the course of providing health care in the current era. In particular, financial recoveries from completed health-care fraud investigations returned an estimated $15 billion to $16 billion to the federal government between 2006 and 2011, while qui tam relators (whistle-blowers) received an estimated $2 billion to $3 billion for their collaboration.

Most importantly, the space of health-care fraud is dominated by pharmaceutical manufacturers—much more than they had previously. Pharmaceutical manufacturers now account for 30% of all federal health-care fraud cases and 70% of recoveries vs 4% of cases and 39% of recoveries previously (prior to 2006), 3 while cases not initiated by qui tam relators are increasingly important.

Specific fraudulent activities involving the pharmaceutical industry in both time periods included overcharging Medicaid and off-label marketing. However, it should be noted that concealing findings on drug safety is a new fraudulent activity (accompanied by large fines and settlements) that has not been reported previously—as outlined in the $3 billion settlement with GlaxoSmithKline.4

Health-care provider systems and hospitals are emerging areas for False Claims Act investigation, now accounting for 25% of False Claims Act cases and 15% of recovered funds. Our findings suggest that accountability initiatives recently developed for banks and their executives5 should be extended to include all sectors of health care; executives of these corporations must be held personally liable if the corporate culture of the health-care industry is to be improved and fraud decreased.

These findings have important implications for health care in general, and the discipline of oncology in particular. Oncology pharmaceuticals account for the majority of high-priced pharmaceuticals, and, hence, are the target of many of the federal investigations related to the False Claims Act. It is incumbent on oncologists to pay close attention to the medical necessity or safety of pharmaceuticals prescribed, and where kickbacks may be occurring. As oncologists, we can play an important role in the health-care system—particularly when oncology pharmaceuticals are involved. ■

Disclosure: This work was funded partly by the National Cancer Institute, the American Cancer Society, the South Carolina SmartState Program, and an unrestricted grant from Doris Levkoff Meddin to the South Carolina College of Pharmacy Center for Medication Safety and Efficacy. Drs. Lu, Chen, Qureshi, Sartor, and Bennett reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Institute of Medicine: Best care at lower cost. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2012. Available at www.iom.edu. Accessed February 9, 2015.

2. Almashat S, Wolfe S: Pharmaceutical industry criminal and civil penalties. Available at www.citizen.org. Accessed February 9, 2015.

3. Kesselheim AS, Studdert DM: Whistleblower-initiated enforcement actions against health care fraud and abuse in the United States, 1996 to 2005. Ann Intern Med 149:342-349, 2008.

4. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs: GlaxoSmithKline to plead guilty and pay $3 billion to resolve fraud allegations and failure to report safety data. Available at www.justice.gov. Accessed February 9, 2015.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the authors and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO.

Dr. Lu is Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Outcome Sciences, University of South Carolina College of Pharmacy, Columbia. Dr. Chen and Dr. Quereshi are Assistant Professors, Health Services Policy and Management, Arnold School of Public Health, Columbia, South Carolina. Dr. Sartor is Medical Director, Tulane Cancer Center, New Orleans. Dr. Bennett is Frank P. and Josie M. Fletcher Professor of Pharmacy, University of South Carolina College of Pharmacy, Columbia.