I still remember having to sit down with her three siblings on that afternoon. It was drizzling, cloudy, and cool—Mother Nature in agreement with the heaviness of what had just taken place. I held them tight. I knew the words I would utter next would change their lives forever. I paused for 10 seconds to search for the right words as six anxious eyes looked back at me—desperately hoping I would tell them she was coming back home. Instead, I was to tell them that their Ruth, their everything, their older sister, and mother figure, had passed away.

“Ruth went to God.”

Being a person of faith, I chose those words. Ruth’s siblings, aged 12, 8, and 5, knew exactly what that meant. And that moment, the inconsolable children, the walk to the next door to be reunited with their parents, witnessing hearts being shattered forever, haunts me to this hour.

Benyam Muluneh, PharmD

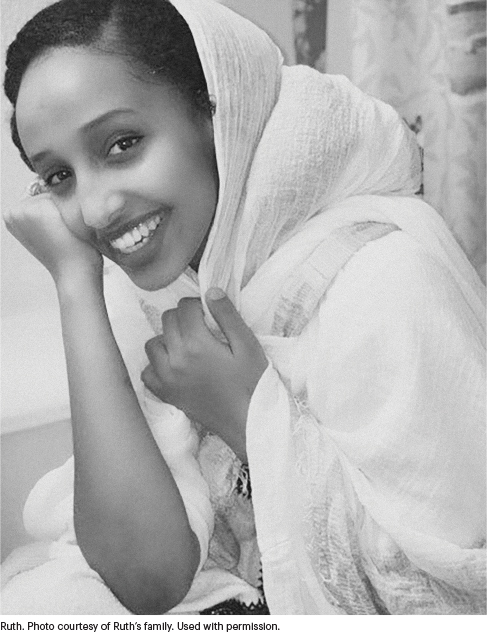

A Warrior With a Smile

A close family friend, Ruth was a vibrant 19-year-old who had immigrated to the United States in 2010. We were Ethiopian Americans, and our tight knit community relied on each other for support. I served as Ruth’s mentor, sharing with her strategies to navigate life as a first-generation immigrant—carefully balancing the joys of success with the obligations of giving back to those less fortunate than us. She had the kindest soul and a humble spirit but fought for her principles like no other. She was a warrior with a smile.

After a traumatizing year of a never-ending pandemic and persistent racial injustice, our community was devastated by Ruth’s diagnosis and eventual death from rhabdomyosarcoma. Over the past 6 months, our small community—including her parents and siblings—has been reflecting on her incredible impact during her short time with us.

As an oncology clinician, I have grappled with the idea of death and dying for quite some time. I was moved to write this piece as I processed my own grief and came to the realization that a key antidote to the frequent loss around us is to remember—and carry on—the legacies of those individuals. Although I was her mentor, Ruth taught me three important virtues during her time with advanced rhabdomyosarcoma: gratitude, advocacy, and service. Honoring these virtues has been one step toward finding a sense of healing for me.

Gratitude

The first virtue is gratitude. From the moment Ruth was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma until her last days on this Earth, she had incredible wisdom to appreciate the “small wins.” Even as she recounted her darkest hours—the neuropathy from the vincristine, the burns from the radiation, and the agony from nausea or vomiting—she would take a moment to note she was still thankful to have that day to spend with her family. I often did not know how to advise her. I just listened to her—and learned from her.

To Ruth, cure at any cost was not the goal. The journey was more valuable. And she focused on finding a sense of peace and acceptance no matter where that journey took her. Ruth knew the reality of her prognosis. Instead of marching forward to a goal that would never come, she stopped to enjoy what she did have. Laughter with her siblings. Melodies with her friends. Ethiopian soap operas with her parents. Ruth’s faith and thankful nature allowed her to accept what was coming until the very end.

One Sunday afternoon, she gathered her family and friends around her. She asked someone to play a kirar (a five-stringed acoustic Ethiopian instrument used in ecclesiastical music) and sang a beautiful hymn (translated in English to “Your love sustains me in all my days”). After she finished singing, she smiled in gratitude, knowing her time had come. She slowly walked back to her room to rest on her bed. She left us the next day.

Advocacy

The second virtue is advocacy. While Ruth was undergoing treatment, there was a national conversation about racial justice and health disparities. Ruth and her family—Black immigrants with no prior interaction with a complex health system—often faced insurmountable obstacles. Ruth initially developed severe migraines and unilateral eye pain. She presented tearfully to the emergency department numerous times asking for help. But as we have seen far too many times, Ruth became another statistic: A young Black woman dismissed in the emergency room while presenting with pain.1 No scans. No diagnosis. She told me about these visits. Her frustration was palpable.

After several months of this back and forth and her relentless self-advocacy, she was referred to a neurologist. During this virtual visit, Ruth knew she had to be persistent to be taken seriously and receive the proper workup. She and I discussed her desire to remain polite as to not appear “too angry”—to avoid an unconscious bias against Black women that often leads to their being dismissed. At the end of the visit, reluctantly, the neurologist did a visual examination, noticed ophthalmoplegia, and told her to rush back to the emergency room: This time the hematology-oncology team was going to see her.

Ruth’s primary oncology team—especially her attending physician—was truly incredible. But she routinely faced disrespect and dismissal by staff toward her and her family. As a first-generation immigrant, I knew exactly the situations she described. I have been in numerous circumstances in which my parents have been ignored or spoken to condescendingly by health-care staff—their accents often serving as a source of annoyance and being interpreted as unintelligence.

Very few people had the time or empathy to slow down and explain what was going on at every step. My wife, a pediatric oncologist, and I, an oncology pharmacist, tried to fill the gap for Ruth where we could. She often felt lost in the morass of a complex and bureaucratic health-care system, but she politely advocated for higher quality and empathetic care whenever she could. This type of cordial advocacy was straight out of another Ruth’s playbook. Ruth Bader Ginsburg once said “you can disagree without being disagreeable”—a lesson in civil opposition.

Service

The third virtue is service. Ruth’s dedication to serving others was inspiring. Her dream was to become a physician and make a difference in people’s lives. During weekends and evenings, she was found volunteering in local soup kitchens, bringing smiles to autistic children, visiting local homeless shelters, and fundraising for humanitarian causes in sub-Saharan Africa. What made her attitude of service so unique, however, was her ability to see the dignity and humanity in individuals who were otherwise shunned by society.

During her funeral, dozens of individuals testified in person and virtually that Ruth had reached out to them during a difficult time and had given them hope, often a reason to live. For example, an older gentleman with psychosis, who many people had avoided, spoke with tears in his eyes: “Ruth was the only one who thought I mattered. She told me I had value. I am devastated.” Her empathy and kindness toward the less fortunate were especially magnified after her diagnosis.

In the months before her death, she began working with a nonprofit organization aiming to provide basic food and health care to children in Ethiopia. Her official volunteer materials arrived at her family’s house within a week of her passing. Her family has vowed to carry on her legacy of service.

A Different Existence

The virtues of Ruth—gratitude, advocacy, and service—will always stay with me and so many others who knew her. These virtues have changed how I practice clinical pharmacy and how I love and care for my family. In her sickness, she taught us how we should heal others. Despite her suffering, she taught us how to smile. As she heard the beeps and drips of the intravenous pole, she sang us beautiful songs. Although she was rushing back and forth to the emergency room, she reminded us to slow down and breathe. While she was dying, she taught us all how to live.

In the Ethiopian Orthodox Church tradition, death is a mystical concept. It is not considered the end of an individual, rather the transition into a different phase of being. A graduation of sorts into a different existence. And I have no doubt that wherever she is now, Ruth is virtuously serving everyone around her forevermore.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Muluneh has an immediate family member who works for Novartis and has stock and other ownership interests in Novartis.

REFERENCE

1. Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, et al: The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277-294, 2003.

At the time this article was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Dr. Muluneh worked in the Division of Pharmacotherapy and Experimental Therapeutics, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chapel Hill.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.

Originally published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology 40:213-214, 2022. © American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.