GUEST EDITOR

Jamie H. Von Roenn, MD

Addressing the evolving needs of cancer survivors at various stages of their illness and care, Palliative Care in Oncology is guest edited by Jamie H. Von Roenn, MD. Dr. Von Roenn is ASCO’s Vice President of Education, Science, and Professional Development.

Although advances in such cancer therapeutics as immunotherapy are significantly prolonging life for some patients with advanced cancer, they are also complicating clinicians’ ability to accurately estimate prognosis and advise patients about their end-of-life options. The result is patients often do not fully understand their prognosis and goals of treatment and are shocked when their cancer progresses and they are told their life expectancy is short.

Only about 10% to 15% of solid tumors will respond to immunotherapy. However, patients are expecting a percentage closer to 80% to 90%.— Eric Roeland, MD

Tweet this quote

“Patients see ads about new cancer therapies touting ‘We are curing cancer’ and come into our offices insisting on getting a drug they saw on television, even if the drug isn’t for their type of cancer,” said Eric Roeland, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Diego. “Immunotherapy is very promising and effective in select circumstances. But when we look at all solid tumors, only about 10% to 15% of those cancers will respond to immunotherapy. However, patients are expecting a percentage closer to 80% to 90%. Trying to prognosticate and support patients and caregivers in this setting is very difficult.” Effective patient-clinician communication about prognosis and end-of-life preferences is essential to quality cancer care and can be aided by the integration of palliative care into oncology care early in the course of a patient’s disease, according to Dr. Roeland.

This past fall, Dr. Roeland addressed the prognostic challenges posed by immunotherapy at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium. During his presentation, he stressed the importance of clinicians using their brain, gut, and heart as a necessary combination of human factors to help patients understand their prognosis and what to expect regarding the likely trajectory of their cancer.

The ASCO Post talked with Dr. Roeland about the importance of preserving realistic hope while helping patients prepare for the unexpected; how to use multiple human factors to communicate prognosis; and how to integrate palliative care into oncology care to ensure patients receive care that is concordant with their goals and preferences throughout their cancer trajectory.

Model of Hope

How do you begin a conversation with your patients about the uncertainty of accurately predicting disease prognosis and their response to an immunotherapy?

The first thing I do is to check in with my patients about their understanding of their cancer and its response to immunotherapy. It is important to teach patients that we may need 2 to 3 months to determine whether the immunotherapy is working. I begin by assessing how they best learn information and ask how they would like me to convey information, such as through words, numbers, graphs, or pictures, and I tailor my communication around their learning preferences. I often also provide patients with written material, links to websites, or audio files to take home, so they can be better informed to facilitate a greater understanding of the benefits and limitations of these new therapies.

Our ability to prognosticate with any accuracy gets worse the longer we know patients, because we become emotionally attached to them and their outcomes.— Eric Roeland, MD

Tweet this quote

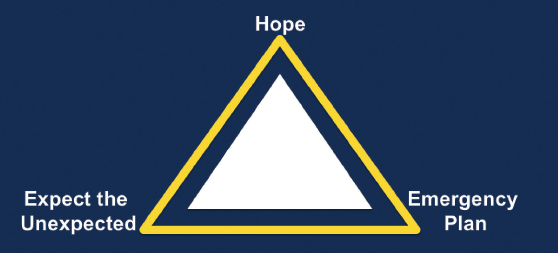

During our conversation, I draw a triangle to capture three key elements of preparing for the future, including hoping for the best, developing an emergency plan, and expecting the unexpected (see Figure 1 on page 80). Then I quiz them about their understanding of what this framework means throughout their cancer experience.

It is always amazing to me that despite these efforts, there is such an intense focus on achieving a grand slam with immunotherapies, and there is so much hope for their success, patients are reluctant to develop an emergency plan. When patients do end up in the emergency room or are hospitalized, we need to revisit their goals and encourage them to develop an emergency plan for the future.

We need to do a better job of communicating with patients about the uncertainty of prognosis with the use of immunotherapies and the potential for treatment-related toxicities and how they may impact quality of life. This is a not a single event, and the conversation may need to be repeated throughout the course of treatment, because patients and caregivers are often overwhelmed and may not hear or absorb the information until it is relevant. For example, they may not want to talk about planning for emergencies until they have experienced an emergency.

Understanding Prognosis

What do you mean when you say physicians have to use their brain, gut, and heart to guide patients in understanding their prognosis?

The brain signifies knowing the available facts about the disease and understanding the prognostic indicators about a specific cancer and its likely course. The gut refers to physicians using their real-world, bedside, clinical experience to prognosticate. The heart alludes to how we communicate this information to our patients, caregivers, and colleagues in a way that is compassionate, truthful, and understandable. And sometimes the most honest answer to give patients when they ask how long they might live is “I don’t know.”

Many of my colleagues are uncomfortable admitting that to patients, but increasingly, as treatments improve and extend survival, it may be the right answer. The pace of development of these promising drugs often leaves clinicians with more questions than answers. Helping patients cope with this type of uncertainty is what is most important. It is key to recognize the limitations of our own medical understanding while at the same time emphasizing the continued support of the clinical team in this uncertainty.

When my patients ask “How long do I have to live?” my first response is “Why do you ask?” I learn so much from that interaction. Usually the patient is asking about prognosis because there is an important event—a child’s birth, graduation, or wedding—he or she would like to attend. Having this information allows physicians to support their patients in understanding how possible their future goals may be. In some cases, the patient’s goals may not be realistic, and then you can explore how he or she may still be present at those important events through legacy activities, such as writing or a video.

Frequently, physicians will give patients the median overall survival of a specific cancer, but I don’t think patients always understand what that means for them personally. Furthermore, we also need to remember and support our colleagues who may be struggling with this issue as well. For example, I recently reviewed prognostic documentation at my institution to see how often members of our palliative care team documented patients’ prognoses after consultations. Surprisingly, I found prognosis was very rarely noted.

I know my palliative care colleagues are excellent clinicians and are actively assessing prognosis, but I wondered why they weren’t documenting this information. Was it because of a lack of knowledge about prognostic indicators (ie, the “brain”); was it because palliative care physicians were afraid of being wrong in their predictions; or was it because they were afraid of offending their medical oncology colleagues; or all of the above?

To find out, we developed a website with more than 60 prognostic indicators and calculators that could be used across a variety of diseases and made it accessible to the palliative care team. But in over 6 months, the website was rarely used, which indicated to me that even when prognostic information is available, clinicians may not feel comfortable using it because it may go against their clinical experience, and/or they may not be sure how to communicate the information to patients, caregivers, and colleagues.

Giving Prognosis in Time Frames

In your practice, you avoid giving patients a specific number regarding prognosis. Why?

The process of prognostication is a humbling experience. As a result, we are trained in palliative care to give survival estimates in broad time frames. For example, we will give information in hours to days, days to weeks, weeks to months, and months to years. And the reason is because of our inability to predict prognosis with accuracy. The only time clinicians are good at prediction is when patients are actively dying.

Studies show that oncologists tend to overestimate prognosis between four and five times, and our ability to prognosticate with any accuracy gets worse the longer we know patients, because we become emotionally attached to them and their outcomes. Clinicians are human, and we need to be aware of our own limitations.

Improving Clinician-Patient Communication

How can oncologists communicate prognosis to their patients effectively and compassionately?

When patients understand their prognosis is poor, it gives them the opportunity to acknowledge they will probably miss future important life events as well as the time to communicate their wishes to family and friends to resolve conflicts or concerns they may have. When life expectancy is likely to be short, I share the information using language that matches the patient’s level of education and then pause to give the patient time to absorb what I have said; then I ask whether he or she understands. Sharing more information while the patient is still emotionally processing prognostic information is ineffective.

A social worker once taught me that when patients hear bad news, their limbic system (the emotional part of the brain) takes over, and patients need time to process the news before they can take in additional information. When the patient is ready to continue the conversation, I answer any questions and make a plan for the next steps in the patient’s care.

Additionally, I want to stress there is ample opportunity for oncologists to collaborate with palliative care clinicians to help ensure their patients are informed and receive care that is concordant with their goals and preferences. As an oncologist and palliative care specialist, I know we can do that better with mutual cooperation and parallel learning.

For example, I launched a palliative oncology journal club at our institution to bring palliative care physicians and medical oncologists together to talk with each other about their concerns and to learn from each other. We need more co-mingling and co-education to improve clinician-patient communication to feel more comfortable counseling patients about their prognosis and to assist them with emergency planning, especially in an era of growing prognostic uncertainty. ■

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Roeland reported no conflicts of interest.