In an analysis reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Fengmin Zhao, MS, PhD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and colleagues assessed factors associated with pain severity changes in ambulatory patients with invasive solid tumors (breast, prostate, colon/rectum, or lung) in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E2Z02 (Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns [SOAPP]) trial.1 They found that approximately one-third of patients with pain at baseline had pain improvement and one-fifth had worsened pain during 4 or 5 weeks of follow-up and that pain developed in 28% of patients without pain at baseline.

Study Details

The study involved 3,106 patients with invasive cancer of the breast, prostate, colon/rectum, or lung. At baseline and at 28 or 35 days, patients rated their pain level on a 0 to 10 numeric scale (MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, 10 = worst pain). A 2-point change in pain score was defined as a clinically significant change. Pain ratings of 1 to 3 were considered as mild, 4 to 5 as moderate, and 6 to 10 as severe pain.

A total of 2,761 patients (88%) who reported pain scores at both initial assessment and follow-up were included in the analysis. Among these patients, 50% had breast cancer, 24% had colorectal cancer, 10% had prostate cancer, and 16% had lung cancer.

Patients were categorized into subgroups consisting of patients with pain at initial assessment regardless of analgesic use (group 1), those without pain and taking no analgesics at initial assessment (group 2), and those without pain and taking analgesics at initial assessment (group 3).

The Pain Management Index, calculated by subtracting pain score from analgesic score, was used to measure the adequacy of pain treatment. The index ranges from –3 (patient with severe pain receiving no analgesic drugs) to +3 (patient receiving strong opioids and reporting no pain. Patients were dichotomized into two groups based on index values of < 0, indicating undertreatment, and ≥ 0, indicating adequate treatment.

Changes in Pain Severity

Of the 2,761 patients, 47% had pain at the initial assessment (group 1, n = 1,298) and 53% had no pain (group 2 = 909, group 3 = 554). Among all patients, 23.5% had mild pain, 10% moderate pain, and 13% severe pain at initial assessment compared with 26%, 11.5%, and 14% at follow-up.

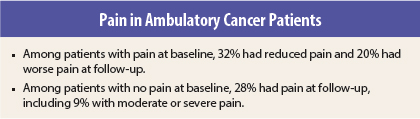

Among group 1 patients (pain at baseline), 32% had reduced pain, 20% had worse pain, and 48% had stable pain at follow-up. The proportions of group 1 patients with pain improvement and worsening varied by baseline pain level; improvement vs worsening occurred in 16% vs 26% of those with mild pain, 40% vs 22.5% of those with moderate pain, and 56% vs 6% of those with severe pain at baseline. Among group 2 and 3 patients combined (no pain at baseline), 28% had pain at follow-up, including 19.5% with mild pain, 5% with moderate pain, and 4% with severe pain.

Changes in Pain Management

Among all patients, 55% had adequate pain management at both visits, 11% had adequate pain management at baseline but were undertreated at follow-up, 10% were undertreated at baseline but had adequate pain management at follow-up, and 12% were undertreated at both visits.

Patients in group 2 had the highest proportion of change from adequate pain management to undertreatment (20% vs 8% for group 3 and vs 7% for group 1; P < .001 for both). In group 1, patients with severe pain at initial assessment had the highest proportion of undertreatment at both visits (35% vs 20.5% for mild pain and vs 22% for moderate pain at baseline; P < .01 for both).

Among group 1 patients, the proportion of patients with worsening pain was highest for patients with pain management that changed from adequate to undertreated (67%), whereas patients with management that changed from undertreated to adequate were more likely to have pain relief (64%; P < .001 for both) regardless of pain level at initial assessment.

Among group 2 patients, 23.5% had developed pain at follow-up, with 85.5% of these patients receiving inadequate pain management. Among group 3 patients, 36% had pain at follow-up, with 21% of these patients receiving inadequate pain management for the recurrent pain.

Factors Predictive of Worsening Pain

Multivariate logistic analyses adjusted for factors associated with worsening pain in group 1 patients and for factors associated with development of moderate-to-severe pain in group 2 and group 3 patients. Factors significantly associated with worsening pain (all P < .05) in group 1 patients included change in pain management from adequate at baseline (odds ratio [OR] = 0.68) to undertreated at follow-up (OR = 11.8). Increased odds of worsening pain were also associated with patients who had the following characteristics at baseline: neuropathic pain (OR = 1.97) or pain due to moderate-to-severe constipation (OR = 1.69), comorbidity-related discomfort (OR = 1.57), greater number of medications currently taken (OR = 0.57), lung cancer (OR = 0.44 for prostate vs lung, OR = 0.45 for colorectal vs lung), unemployment (OR = 2.05 vs full employment), and treatment in community institutions (OR = 2.22 vs academic institutions).

Factors significantly associated with occurrence of moderate-to-severe pain in group 2 patients on multivariate analysis (all P < .05) consisted of Hispanic ethnicity (OR = 3.38), constipation severity (OR = 1.18), and age < 55 years (OR = 2.28). Factors significantly associated with moderate-to-severe pain in group 3 patients (all P < .05) consisted of nonopioid (OR = 2.09) or weak opioid (OR = 3.96) vs strong opioid use, years since cancer diagnosis (OR = 0.89), and accompaniment to study visit (OR = 2.09).

The investigators concluded, “One third of patients have pain improvement and one fifth experience pain deterioration within 1 month after initial assessment. Inadequate pain management, baseline pain severity, and certain patient demographic and disease characteristics are associated with pain deterioration.”

They noted, “[P]ain remains a significant concern in ambulatory oncology. Pain is not only prevalent but also persistent and dynamic.

Knowing that pain management practices and baseline pain severity are key factors for change in pain severity should enable better designs of clinical trials intended to measure the impact of cancer therapeutics or supportive care measures on the short-term patient experience of pain.” ■

Disclosure: The study was supported by National Cancer Institute and MD Anderson Cancer Center grants. The study authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Zhao F, Chang VT, Cleeland C, et al: Determinants of pain severity changes in ambulatory patients with cancer: An analysis from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial E2Z02. J Clin Oncol. December 23, 2013 (early release online).