It is well documented that the rigors of delivering cancer care can unintentionally supersede valuable doctor-patient communication. Before he died in 1995, Kenneth B. Schwartz, a patient with cancer at Massachusetts General Hospital, recognized this phenomenon and founded the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, a nonprofit organization that sponsors the Schwartz Center Rounds, a forum dedicated to improving the special relationship between doctors and their patients. To gain insight into the Rounds, The ASCO Post spoke with long-time Rounds participant and advocate, Richard T. Penson, MD, MRCP, Clinical Director of Medical Gynecologic Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

It is well documented that the rigors of delivering cancer care can unintentionally supersede valuable doctor-patient communication. Before he died in 1995, Kenneth B. Schwartz, a patient with cancer at Massachusetts General Hospital, recognized this phenomenon and founded the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, a nonprofit organization that sponsors the Schwartz Center Rounds, a forum dedicated to improving the special relationship between doctors and their patients. To gain insight into the Rounds, The ASCO Post spoke with long-time Rounds participant and advocate, Richard T. Penson, MD, MRCP, Clinical Director of Medical Gynecologic Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Origins of the Organization

Can you give the readers some insight into the founder of the Schwartz Center?

Kenneth Schwartz was a 40-year-old health advocacy lawyer with a 10-year-old son when he was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. His journey as a patient with cancer, from diagnosis to death, reinforced his experience as an advocacy lawyer that the central place of compassionate care was being eroded from the medical profession. His response was to set up an organization that would advocate for, and advance methods to strengthen, the caregiver-patient relationship. Ironically, that is probably more of a key issue now than it was in 1995, when Kenneth Schwartz died.

Success Story

Who participates in the Rounds?

Who participates in the Rounds?

Currently, there are about 50,000 clinicians and other medical staff who attend monthly Schwartz Rounds at 240 sites in 35 states—numbers that continue to grow, which is a pretty impressive rate of growth, given the organization’s 16-year history.

What are the factors that have made the Rounds so successful?

A key to success is having effective leadership to rally the medical staff to attend the Rounds. Although there are various people from all spectra of medicine, from research scientists to clergy, much of the group’s initiative comes from clinicians. Hearing clinicians talk openly about caring for people with life-threatening diseases ignites discussion about the emotional and social challenges faced by caregivers.

Ultimately, clinicians speak frankly about their frustrations in seeing some of their patients show disease progression and treatment failure, but they also share clinical “pearls”—not just how to give outstanding cancer care, but how to deliver compassionate care.

Personal Perspective

On a personal level, how have the Rounds affected you?

On a personal level, how have the Rounds affected you?

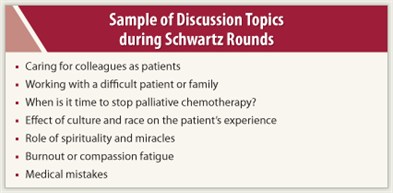

When I began my career in medicine, in my naiveté, I thought that everyone loved what he or she did. But as I got older, I noticed more burnout-associated problems. My guess is that all generations of clinicians face the same issues associated with long-term stress. It is very hard to deliver high-quality, cost-effective, and compassionate cancer care over a long period without catching some of the emotional flack, or grieving over the losses. That’s a demanding characteristic of the profession.

A popular software adage notes, “you can have it quick, cheap, or effective, but you can’t have all three.” And I think that’s also the case with today’s health care, in that we are all very concerned that the mounting pressures of providing cost-effective care will further distance the clinician from the patient. So these topics—being too busy, burnt out, or emotionally bruised—are some of the recurring themes visited during the Rounds.

Burnout in Oncology

Burnout is an issue that has gotten better-deserved attention over the past few years. How has it been addressed in the Rounds?

We regularly raise issues surrounding burnout. Staff are a vital but vulnerable resource and can burn out under the incessant pressure of patient care. Sometimes we are overcommitted, overstretched, and just too busy.

We regularly raise issues surrounding burnout. Staff are a vital but vulnerable resource and can burn out under the incessant pressure of patient care. Sometimes we are overcommitted, overstretched, and just too busy.

We often discuss issues that affect the whole care team—for instance, communicating with a team member who aggressively gives ineffective and costly care at the end-of-life. I’d say that burnout comes up as a subject every 3 or 4 months. The truth is that we are often preoccupied with the demanding medical aspects of our patients, their families, and our colleagues, and feelings of frustration, anger, and helplessness too often go unaddressed. I love my job, and it’s a tremendous privilege, but there is a definite human cost in cancer care. Every so often you need to renew the original passion that led you to becoming a doctor who cares for people with life-threatening illnesses, many of whom will die under your care.

Measuring Benefits

As one who participates in Rounds, can you quantify any benefits from this model?

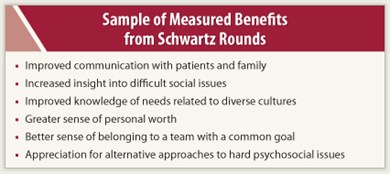

Yes, in fact there’s been an external audit that found numerous benefits. For example, participants stated that Rounds discussions led to an increased ability to respond to patients’ social and emotional issues, which led to a greater sense of teamwork, more appreciation of their colleagues’ contributions, and a decreased sense of isolation and stress.

Moreover, participants reported that Rounds often led to changes in institutional practices or policies. I think there are also measurable and sustained changes in behavior, but these have not been formally evaluated. Ultimately, the Rounds process benefits our patients by making us more aware of key issues, and fostering real support and connection between clinicians and patients.

Impact on Career

How have the Rounds affected your career?

In medicine, there is the principle of “see one, do one, teach one,” and a recommendation that comes up during Schwartz Rounds can be a useful bit of guidance along those lines. In particular, physicians are often like well-intentioned amateurs when it comes to social, psychological, and spiritual issues. For me, being involved in Schwartz Rounds has served my patients and me by continuing to remind me why I’m doing this difficult but extremely rewarding work.

One aspect of the Rounds that I’ve found particularly helpful in terms of inspiration is not so much connecting with patients with whom I already have a good rapport, but dealing with those who have very difficult problems and are hard to like. A couple of years ago during the Rounds, a psychiatrist gave this tip: Look into the difficult patient’s eyes and articulate something that you admire about that person. For instance, you could say, “With all that’s going on in your life, I really admire the way you’re able to…,” then fill in the blank. It works; it’s a small but meaningful way to show that you are giving them your full attention, and that you care.

The Rounds have had a profound impact on my career because in solid tumor oncology we only cure a few, but we must care for them all. And to achieve that total care package, day after day, requires a committed self-renewal and reconnection with the patient. That is what Schwartz Rounds is all about. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Penson has received research funding from Lilly, ImClone, Endocyte, AstraZeneca, Amgen, and Eisai. He has been on scientific advisory boards for Genentech, Biomarin, Lifecore Biomedical, and Clovis.