ASCO President-Elect Eric J. Small, MD, FASCO, developed much of his multicultural world view during his childhood in Mexico City. “My parents were expatriates who moved to Mexico in the 1950s and settled there. I was born in Mexico City and grew up bilingually. I went to an English-Spanish speaking school called the American School, where half my friends were Mexican. I knew kids from all around the world but really grew up speaking Spanish. I have always identified Mexico as my emotional home,” he shared.

ERIC J. SMALL, MD, FASCO

TITLE

Co-Leader, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Prostate Cancer Program; Deputy Director and Chief Scientific Officer, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, FASCO: Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio

ON WHAT IT MEANS TO BE AN ONCOLOGIST

“There is no greater privilege, no higher calling, than the capacity and ability to take care of people with cancer. Ultimately, I think this is true for almost everyone in the field. What sustains us is the primacy of that relationship, being able to help patients through each segment of their journey with cancer. For me, it’s almost a sacred kind of thing. It’s not to say we don’t have problems facing us as a profession, we do, but we have to address them to ensure that future generations of oncologists find this same joy, meaning, and drive.”

According to Dr. Small, his parents instilled in him a sense of duty to make a difference in the world. As a child, Dr. Small nurtured a deep love of science. After graduating from high school in Mexico, he decided to go the States for his undergraduate work, entering Stanford University in 1976 as a biology major.

Asked about his decision to pursue a medical career, Dr. Small replied: “I’m not one of those people who wanted to do premed when I was in high school; I actually had other interests. For one, I was very gregarious and wanted to do something that involved deep interactions with people. It wasn’t until the end of my undergraduate year that I realized medicine was a way to bridge my love of science and my people skills together. It was not a terribly informed decision, but it was the right decision for me.”

After attaining his BS in biology from Stanford University, Dr. Small went to Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland. “Case Western was a great choice for me. At that time, it was very much a humanistic institution, focusing on a whole-person medical approach, which is standard now but not as much back then. Prior to that, I’d never spent a day in the Midwest, so it was a bit of a culture adjustment for a kid who was educated south of the border,” he explained.

A Valued Mentor Helps a Career Choice

At Case Western, Dr. Small began doing laboratory work in benign hematology with Oscar Ratnoff, MD, one of the pioneers in clotting factors. “Working with Dr. Ratnoff was when I first began to understand what we now call translational science,” Dr. Small commented. “Dr. Ratnoff would have patients with terrible bleeding disorders who were referred to him from all around the world because he had discovered one of the principal clotting factors in his lab. And so that’s when it began to click that medicine and science were dependent on one another. Although I didn’t quite know what I was going to do at that point, the interface of science and patient care was a very formative experience in my career.”

Dr. Ratnoff gave Dr. Small an important bit of advice: ‘Bad ideas die hard.’ According to Dr. Small, “that simple phrase altered my perception of what should and could advance medicine, by allowing the questioning of dogma.”

Dr. Small spent an extra year in medical school to take advantage of a program that offered medical students a 1-year pathology fellowship. During this fellowship, Dr. Small’s interest in cancer began to grow. After attaining his medical degree from Case Western, he traveled East, to Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, for an internship and residency in internal medicine. “All the rotations at Beth Israel were exciting, and I remember really loving cardiology. I’m not quite sure how cancer stuck, except the prior pathology work was percolating back there, and it all just came together,” he explained.

Dr. Small continued: “Although I loved being on the East Coast, as I was completing my residency, I knew I wanted to return to the West Coast and applied to several fellowships. I chose UCSF [University of California at San Francisco] because it had unparalleled science, as it does now. It had a strong commitment to patient care, and that appealed to me. It also was a combined hematology and oncology fellowship, which is what I wanted. I did a year and a half of clinical work and then joined the laboratory of my mentor and friend, Dr. Marc Shuman. He was Division Chief at the time and helped me develop my approach to the scientific method in the lab.”

Under Dr. Shuman’s mentorship, Dr. Small began studying adhesion molecules. In one lab experiment, Dr. Small used a prostate cancer cell as the negative control because the disease was not supposed to present with these specific molecules. “At first I thought these results just represented bad lab technique on my part, but it kept coming up positive, and it turned out these adhesion molecules were in fact present on the prostate cancer cells; up until then, that fact had not been appreciated,” he said. “This observation prompted investigation into the metastatic process, including adhesion and invasion, and in particular in prostate cancer. Once I began to focus on prostate cancer, I realized that there was very little known, either clinically or -biologically, and it just sparked my interest. Not long afterward, Dr. Small began working with Dr. Peter Carroll, a urologist at UCSF. “At the time, a multidisciplinary approach to urologic malignancies was unheard of,” he said. “Dr. Carroll was, and remains to this day, a remarkable colleague who embraced a multidisciplinary approach.” Dr. Small has been at UCSF ever since.

An Environment of Scientific Collaboration

Dr. Small described his early time at UCSF as a “cauldron of remarkable science,” where laboratory scientists and clinical investigators worked in close collaboration. “With Marc Shuman’s help, I began to develop a lot of important relationships with researchers, one of whom was Dr. Jim Allison, who deservedly won the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work in checkpoint inhibitors. Jim and I became collaborators in the first clinical investigation into ipilimumab, testing it on one of my patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. This was the very first patient treated with ipilimumab, and even with one dose, we saw activity,” he shared.

Findings of the drug’s activity were published in Clinical Cancer Research in 2007, which initiated further investigations of ipilimumab in other cancers, such as melanoma and kidney cancer, leading the way in the emerging field of immunotherapy. “Another project that we did was the development of sipuleucel-T. Back then, it was basically a homegrown project in an academic center lab. It was picked up by a small company that sought us out. We subsequently undertook the phase I and II trials and led the first phase III trial that eventually led to its FDA approval. The agent is not an absolute home run, but it really established the principle that immune tolerance could be broken in prostate cancer (and in fact, in solid tumors), and that immune therapy made sense. In many ways, that remains a holy grail in prostate cancer. We’ve made small inroads but not as many as we like. That was the kind of environment I was in, and it was just so much fun to be able to interact with these amazing luminaries.”

A Long History With ASCO

Dr. Small has had an extensive connection with ASCO, most notably as former Scientific Program Committee Chair, founding Scientific Program Chair of the ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, and a member of the Board of Directors. Dr. Small most recently served as a mentor in ASCO’s Leadership Development Program, coaching and advising mid-career members to become leaders in oncology.

Asked to share his thoughts on becoming ASCO President-Elect, Dr. Small said: “I’m really excited, because it feels like an opportunity to pay back ASCO for everything it’s done and does, not just for me, but for so many. I became involved with ASCO early on in my career and very quickly realized it was a remarkable organization in bringing together people from disparate walks of life who had the same focus: cancer. It established networks of people who did the same thing as I did. ASCO has always been the place where science meets patient care. Even before it was a thing, ASCO was developing and supporting “translational research,” not only from the lab into patients, but in implementation into communities and broader populations.”

Dr. Small continued: “ASCO has done an amazing job of becoming the global society for oncology. I think that is fantastic and something I want to emphasize. Not only are we all more inter-twined than we ever knew, not only is there a moral imperative to address underserved cancer communities at home and around the world, but the science does not follow borders. From day one, that component of ASCO really appealed to me, and I want to see us continue to do that.

He added: “I am beyond excited to have recruited two Program Committee Chairs for the 2026 annual meeting that will reflect these core beliefs: Jo Chien, MD, a talented translational clinical breast oncologist from UCSF who has agreed to serve as Scientific Program Committee Chair, and Erika Ruiz-Garcia, MD, MSc, who is an educator and a translational scientist and clinical investigator in gastrointestinal oncology, from the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, in -Mexico City, who has agreed to serve as Education Program -Committee Chair.”

‘No Greater Privilege’

Asked to share some thoughts on his career as an oncologist, Dr. Small replied: “There is no greater privilege, no higher calling, than the capacity and ability to take care of people with cancer. Ultimately, I think this is true for almost everyone in the field. What sustains us is the primacy of that relationship, being able to help patients through each segment of their journey with cancer. For me, it’s almost a sacred kind of thing. It’s not to say we don’t have problems facing us as a profession; we do, but we have to address them to ensure that future generations of oncologists find this same joy, meaning, and drive.”

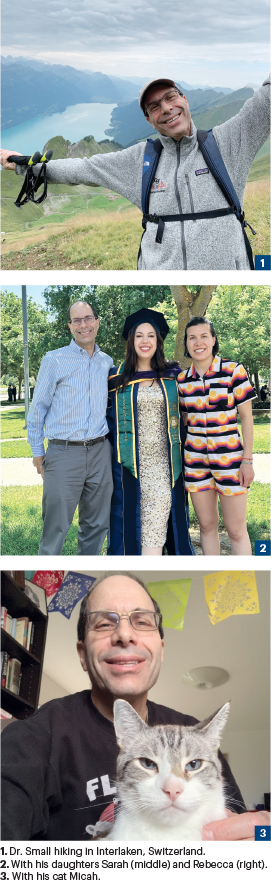

Family, Cats, Exercise, Baking

How does a super-busy oncology leader decompress? “I love to bake, so I picked this up during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Small shared. “I’d always done some baking for my kids, but now I do all sorts of cakes, pastries, sweets, and bread; I try to find people to give them to because I just cannot have them at home. The joke has always been that if I don’t make it as an oncologist, I can try to sell my cookies on the street! I also exercise and run, which helps me decompress a lot. I have two daughters of whom I’m incredibly proud. My older daughter, Rebecca, is a nurse practitioner who trained at UCSF and works in women’s health. My younger daughter, Sarah, who graduated from UC Davis Law School a year and a half ago, is doing environmental law. Then there are my two cats; as anyone who has animals knows, they are the perfect way to center yourself and feel attached to something. They also remind you that they, not you, are the center of the universe!”