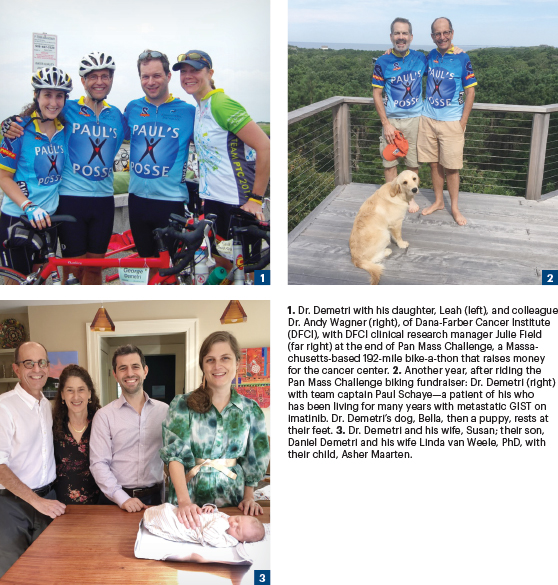

George D. Demetri, MD, FASCO, Director of the Sarcoma Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Professor of Medicine and Co-Director of the Ludwig Center at Harvard, was born in Hyde Park, a town along the Hudson River in New York. When Dr. Demetri was growing up there, it was known for three things: sprawling dairy farms, IBM factories, and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“Both sets of my grandparents were immigrants to the United States from Greece before 1920. My dad was orphaned as a child in New York City, so I don’t know much about his family. After learning skills in the Army radio corps in World War II, he worked as a technician at IBM, but he never went to college; nobody in my family had gone to college before me. I was always very proud of my dad because he was part of the teams putting big mainframe computers into NASA’s mission control center,” said Dr. Demetri. “My mom was a school secretary. So even though “secretary” is not viewed as an acceptable term these days, I use it with reverence because she was an able administrator and always supported me in wanting a higher education.”

Mixing Science and Music

Asked when he first thought about medicine as a career, Dr. Demetri responded: “As far back as I can remember, I always had somebody in my family who had cancer. I saw a lot of people from a young age who had cancer with 1960s-type toxicities from cobalt radiotherapy and bad outcomes, and obviously that has an impact on you when you’re a kid. I thought I wanted to be a nuclear physicist when I was in third grade, but I found it incredibly dry and mathematical. Physicians spent time interacting with people, and I liked that a lot, so medicine seemed to have the mix of science and a human touch that really appealed to me. The sense of the transitory nature of life, that death was a part of life, was imbued in my childhood experiences.”

GEORGE D. DEMETRI, MD, FASCO

TITLE

Quick Family Chair of Medical Oncology and Director, Sarcoma Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Co-Director, Ludwig Center at Harvard

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, Stanford University School of Medicine

ON LESSONS LEARNED FOR EARLY CAREER ONCOLOGY FELLOWS

“Surround yourself with brilliant people and soak up their knowledge. I do not consider myself a brilliant laboratory researcher. But Dave Tuveson, Lloyd Old, and Phil Sharp are brilliant researchers. I learned a lot from them, and I developed skills to complement their strengths. I’ve been lucky to be around so many brilliant people in my life.”

Besides an early passion for science and medicine, Dr. Demetri was an avid musician, playing lead guitar in a rock band he started in high school. “We played Grateful Dead covers, typical Led Zeppelin stuff, too. We ultimately became the backup band for an exchange program to Romania when it was under rigid communist rule. In 1974, our band became the second U.S. band to play behind the Iron Curtain after Blood, Sweat & Tears. Rocking an outdoor concern in the center of Bucharest with “Truckin” and “Johnny B. Goode” was a memorable experience. I loved to play, but I knew I wasn’t cut out to be a professional musician.”

When Dr. Demetri entered Harvard College as a joint Philosophy/History of Science major (later changed to biochemistry), he immediately joined the Harvard Jazz Band and soon after that began playing in a jazz-rock fusion group with an eclectic array of talented students from Berklee, MIT, and Boston University.

Detour West

Although Dr. Demetri had hoped to earn his medical degree at Harvard after undergraduate work, he wasn’t accepted.In retrospect, he described this as a blessing in disguise, since he was accepted to Stanford Medical School, which accepted him but also allowed him to hold his spot for a year so that he could accept a Rotary Foundation Fellowship to study science in France for a year.

“I lived in the far eastern part of France, a little town called Besançon, very close to Lausanne, Switzerland. My senior thesis had been on gene regulation from insect steroid hormones, and I was studying human steroid hormone physiology there. The fellowship included a summer language immersion program during which I lived with a French family and went to language classes at the Institut deTouraine every day from 9 to 5. By the end of a month, I was literally dreaming in French. Besançon also had a wonderful music conservatory, and I sang in the chorus. Then I returned to Massachusetts, was a teaching assistant in biology at Harvard’s summer school program, and then drove across the country to begin medical school at Stanford,” he shared.

Needed Patient Interaction

At Harvard, Dr. Demetri’s mentor on his undergraduate thesis, Peter Cherbas, PhD, had tried in earnest to convince Dr. Demetri to pursue a PhD and become a basic scientist, insisting that Dr. Demetri’s penchant for mechanistic problem-solving was the perfect mindset for the lab. However, Dr. Demetri needed patient and family interactions to complement basic science, a balance which he found at Stanford Medical School. Other life changes also happened there as well. “I met my wife on the very first day of school during an orientation week picnic. We’d both lived in France for a year, and we were big Francophiles. She asked what I did before Stanford, and I said I ran SDS-PAGE gels. She drove ambulances in college. We came from different places, but we hit it off,” explained Dr. Demetri.

The path to oncology began taking form, first with Bert Glader, MD, a pediatric oncologist who encouraged Dr. Demetri’s curiosity about why some cancers are cured while most are not. Stanford featured small, intimate classes, and the faculty was staffed by world-class leaders in oncology, such as luminaries Drs. Saul Rosenberg and Henry Kaplan, two of Dr. Demetri’s most valued mentors. “Henry had a misshapen hand, with an enlarged thumb, and he could detect lymph nodes that nobody else could feel.It was an honor to learn how to examine lymph nodes from him. And Dr. Rosenberg was an extraordinary clinician as well. They were thoughtful, deeply sensitive to the needs of the patients, and without big egos. They were really into training the next generation and cared deeply about this. That affected me.”

According to Dr. Demetri, at Stanford, he’d become committed to pursuing a career in oncology, and that decision was amplified by an enthusiastic young researcher named Branimir (Brandy) Sikic, MD, who is currently Professor of Medicine Emeritus in the Division of Oncology at Stanford University School of Medicine. “Back then Brandy was an early drug development guy and had returned from a meeting in Bethesda at the National Cancer Institute. I remember the day he told everybody in the department about this amazing drug called platinum. He said it looks like a miracle, and I thought the future was bright for cancer research,” related Dr. Demetri.

After attaining his medical degree from Stanford, Dr. Demetri and his future wife matched as a couple to the University of Washington, Seattle. “Seattle at that time felt like the other end of the world to both our immigrant families,” he said.

Dr. Demetri continued: “My wife’s parents are Holocaust survivors, and after the war, they were relocated to Stockholm; and after 10 years, they chose to uproot themselves again and moved to New York. My wife’s family used to write us letters on “onion skin” air mail stationary because Seattle seemed like the other side of the world.”

Rich Science Minus the Big Egos

At Seattle, Dr. Demetri’s fiancé pursued a primary care internal medicine track, and he settled into a research/internal residency track. Seattle was a valuable career-building environment for the burgeoning academic oncologist. Over coffee, for instance, he met the voluble transplant pioneer, E. Donnall Thomas, MD. “We got to talking and his daughter was a medical student on my service. So, I heard everything about how he got started and learned about team science from the people at the Fred Hutch like Don Thomas, Keith Stewart, Fred Appelbaum, and Phil Greenberg, to name a few. All were luminaries, and not one let his ego get in the way of working together. It was wonderful to see an academic group that truly lived and breathed team science—before the phrase became popular. I was a chief resident, and there was a resident conference once a month. An older man always came; he was an emeritus professor and sat in the back of the room. One day I asked about the guy who asks all the good questions and learned it was Paul Beeson. I said, ‘Beeson, as in guy who practically discovered eosinophils and wrote the textbook of medicine [Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine; Cecil-Loeb Textbook of Medicine]?’ Yes, that Beeson. That’s just the way it was in Seattle—science first; leave your ego at the door.”

After a valuable learning experience in Seattle, Dr. Demetri realized bone marrow transplantation and leukemia were no longer part of his career trajectory. Instead, he was drawn to solid tumor research; to that end, he interviewed for an oncology fellowship at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, speaking at length with luminaries such as Drs. George Canellos and Jim Griffin.

Dr. Demetri continued: “Jim took two fellows into our group, me and Mark Socinski, MD. So, Mark was the clinical trials guy in Jim’s lab, and I was learning to do Northern blots. And after the first year, Mark discovered that GM-CSF [granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor] makes peripheral blood full of stem cells, full of young progenitor cells that could be useful in transplantation. During this time, I met the people who started Amgen; they were brilliant people who were the generation of the first biotechs. I learned a lot from interacting with them. After my fellowship, I had a chance to return to Stanford, but I stayed at Dana-Farber. I wanted to be right in that pivot point between basic science and clinical care.”

Road to Sarcoma Research

Dr. Demetri’s road to becoming an internationally recognized sarcoma expert began, in some part, with a famous controversy in breast cancer: high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. “When I got to Dana-Farber in 1986, there was still hype about bone marrow transplant and very high–dose therapy in patients with breast cancer. We now know that higher-dose therapy does not necessarily improve outcomes in that disease. But I joined with my mentors in our breast cancer program, people like Craig -Henderson, Don Berry from the CALGB, and Dan Hayes, all of whom wanted to do a study to verify if high-dose chemotherapy was beneficial. And at that time, the new drug called Taxol [paclitaxel] looked pretty good. So, I became the co-leader of the study along with Craig Henderson, Larry Norton, and the NCI Intergroup breast cancer group that was CALGB 9344. That trial showed that higher doses of chemotherapy didn’t do anything, but the key was adding paclitaxel. And that got the drug approved as an important adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, so that was a true learning experience,” said Dr. Demetri.

Soon after, Eric Winer, MD, joined Dana-Farber, he encouraged Dr. Demetri to follow his interest in sarcomas as a unique -vehicle to explore drug development. “And that was also a -wonderful thing because I had been deeply -exploring the science of sarcomas, trying to find ways to link new biologic phenomena, such as the EWS-FLI1 fusion gene discovered by Professor Olivier Delattre in Paris, to clinical care. Fortunately, I had a several wonderful collaborators, including a pathologist named Chris Fletcher, one of the best anatomic pathologists in the world, that Harvard had just imported from London. Chris was outstanding at classifying and parsing sarcomas into tens of different bins, along with a remarkable surgical oncologist, Sam Singer, and a phenomenal radiation oncologist, Beth Baldini, all of whom were also completely committed to sarcomas. After Sam left to go to Memorial Sloan-Kettering, Dr. Monica Bertagnolli (the current NCI director, recently nominated to be the NIH director) became our sarcoma center surgical oncologist, and she recruited Dr. Chan Raut who is the current head of surgical oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.Over the years, our team built a multidisciplinary sarcoma research and care program at Dana-Farber when nobody cared much about this orphan disease. We dug our heels in and went to work.” Dr. Demetri recalled.

The Fun Part of Academic Growth

The fun part was the now-famous collaboration with Brian Druker, MD, which led to the practice-changing drug imatinib. “It was 1999 when Brian presented the plenary session at the ASH meeting in New Orleans. I used to borrow reagents from him when his lab was one floor below the lab in which I did post-doctoral research, so I. went up to him afterward and said, ‘Brian, congratulations. I hope you get the Nobel Prize. By the way, what else does this magic drug of yours hit?’ He said: ‘It hits KIT,’ and I said, ‘That’s exactly what I’m looking for,’ because one of the post-doc scientists from Jim Griffin’s lab had returned to his home in Japan and was a key part of the team that discovered theKIT mutation in this sarcoma called gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GIST]. I asked if he’d introduce me to Novartis, and he said, absolutely.”

The road to a Novartis partnership was an uphill and bruising battle. “The sense I got from Novartis was, ‘This is a small market [GIST]. You’re just going to have to wait 2 or 3 years until we get this drug [imatinib] on the market.’ I told them that ‘in 2 or 3 years, all my current patients with this disease will be dead, so that timeline is not an option.’ Long story short: what I’m most proud of is that a few months later, I’m arguing with Novartis: ‘I wrote an N of one trial for this patient in Finland, and the patient is doing great.’I convinced them to provide me with a supply of the drug for 12 patients at Dana-Farber. So, I write the 12-patient study. Novartis eventually chose to have Dr. Demetri coordinate the first multicenter trial of imatinib in GIST, along with a collaborative team from Finland, Oregon Health Sciences University, and Fox Chase Cancer Center.

“The thing I’m most proud of as an academic is when you have a brand-new drug that’s as revolutionary as imatinib, and you help to collaborate with physicians to determine how best to use it. This is where good marketing and good continuing medical education are completely aligned. So here, we were getting the message out. There’s this new way of treating cancer, but you must learn how to use the drugs and how to do the diagnostics. I was hearing these amazing stories from patients brought back from the edge of death nationwide, and frankly worldwide, and the drug worked,” said Dr. Demetri. In 2020, Dr. Demetri was honored with the David A. Karnofsky Memorial Award and Lecture during the ASCO20 Virtual Education Program for pioneering the development of imatinib and several other “smart” therapies for GISTs and other types of sarcomas.

Asked if he had any advice for young fellows coming into the field of oncology, Dr. Demetri commented: “Surround yourself with brilliant people and soak up their knowledge. I do not consider myself a brilliant laboratory researcher, but Dave Tuveson, Lloyd Old, and Phil Sharp are brilliant researchers. I learned a lot from them, and I developed skills to complement their strengths. I’ve been lucky to be around so many talented and dedicated people in my life.”

Decompression Time: Still About Music

How does a leader in oncology decompress? “It’s still all about the arts. All about listening to music, staying right on top of what the latest hot bands are doing. I have not kept my guitar playing up, unfortunately. It’s the one thing I want to get back to someday. And my wife has said that I’ve been saying that for about 25, 30 years, but someday it might happen that I get my Les Paul re-strung. I also think that it’s good to walk around thinking with ear pods in listening to music. So, I just keep right on top of the latest things that Taylor Swift, Pink, Daft Punk, and Lady Gaga are putting out. I also love what I do in my work, developing new treatments for cancers. It’s the most exciting time ever to be in the field of oncology.”

A Closing Thought

Asked for a closing thought, Dr. Demetri said: “I fully believe that we will have the chance to control at least 75% of cancers in the next 10 to 20 years. And I remain completely optimistic that everything we learn in cancer research will give us insights to provide better care in other diseases, like inflammatory diseases and even neurologic disorders. We live in a global community and the technology allows us to work across borders for the good of patients around the world. Just as democracy started in Greece and spread across the world, we see the scientific and medical advances spread across the world with breathtaking speed. We want to push that as fast as possible because time matters for every patient.”