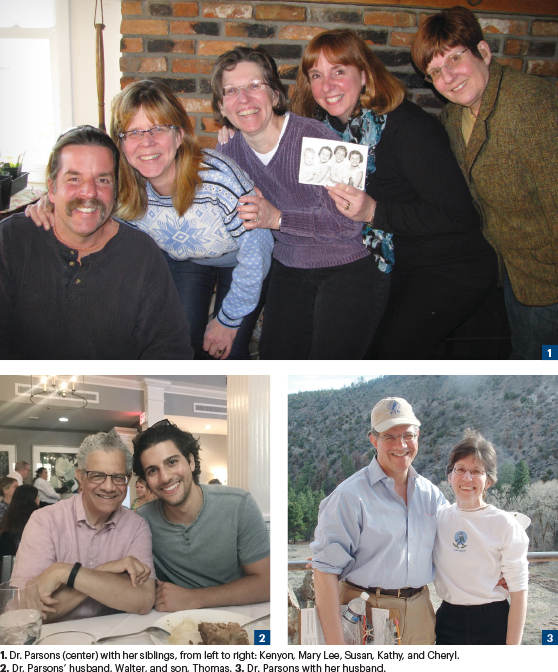

Susan K. Parsons, MD, MRP, Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at Tufts University School of Medicine and Founding Director of the Reid R. Sacco Adolescent and Young Adult Program for Cancer and Hereditary Blood Disorders at Tufts Medical Center, grew up on a working dairy farm in Sharon Springs, a small town in Upstate New York. “I was the third of five siblings, and my family was the center of my life. We had a large farm that included two homesteads—our house on one side of the road and my grandparents’ house on the other side of the road. The edge of the farm was demarcated by a road called Parsons Road, of course!!” she said. “Seemingly every one of my relatives lived on Parsons Road.”

Dr. Parsons continued: “Our old house was built in the 1700s, and there wasn’t a straight edge anywhere; it was so big and ramshackle, that we were able to learn to roller skate in the kitchen and ride our tricycles inside, around the central staircase. We explored our woods and set up all sorts of adventures; it was really a very interesting and free environment for a kid.”

Susan K. Parsons, MD, MRP

TITLE

Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at Tufts University School of Medicine; Founding Director of the Reid R. Sacco Adolescent and Young Adult Program for Cancer and Hereditary Blood Disorders at Tufts Medical Center, Medford, Massachusetts

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York; MRP, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

ON THE FOCUS OF HER CURRENT WORK

“I have moved away from patient care in the acute transplant setting and am more focused now on survivors of cancer. About 10 years ago, I received an incredible gift from a family whose son had died of cancer, and they wanted to set up a program in his memory. The focus is on survivorship among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors."

Asked if she had an early interest in science, Dr. Parsons responded: “I loved to do experiments when I was young, much to my parents’ chagrin; one day, I wanted to see if baking dirt in the oven would change the speed with which a seed might germinate. I remember my mother asking about the horrific smell emanating from the kitchen! Another example was removing limestone rocks off the corner of our house’s foundation to test them for their calcium carbonate content using white vinegar, but my father quickly pointed out my experiment was going to destabilize the entire house. He was the president of our local volunteer library and was able to get a key to the library, so we could even check out books after hours. We could check out only two books at a time, but with five of us, that meant we had a nice stash of books to get us through to the next trip to the library.”

Oats and Epic Poetry

Growing up on a farm entailed hard work, even for the kids, but, as Dr. Parsons recalled, the work was inspiring. “Each of us was assigned a crop, working with either my father or my grandfather on the harvest. I was assigned to harvesting the oats with my grandfather, so I learned how to tie a Miller’s knot, which is the way you seal off the bags of grain. But the most memorable part was my grandfather’s love of poetry. He would be reciting one epic poem after another, and it was just this magical combination of physical work and high-concept poetry that was amazing,” Dr. Parsons recalled.

The Parsons’ children played and toiled on the vast acreage during the prevaccine era, and Dr. Parsons noted that as a kid, she had “every communicable disease you could imagine. As a pediatrician, I take those communicable diseases very seriously. It is a relief that they now can be prevented,” Dr. Parsons stated. That gritty experience helped form her desire to pursue medicine and her later career in pediatric oncology.

“My early exposure to medicine was very limited. We had a single general practitioner in the town who worked harder than anyone I knew. He would make house calls, coming to us on skis or snowshoes, no matter the weather. It wasn’t a life to which I aspired, but it probably had a subliminal effect, as he was such an admirable person, dedicated to caring for the sick.”

A Free Spirit Who Loved to Sing

Dr. Parsons’ early life was marked by the gender-bias endemic of the time, but her free spirit and desire for expression were undaunted. “My favorite memories come from my extracurricular activities with my sisters in music. In addition to being in several singing groups, we also each played a musical instrument. I played the French horn, not well, but with great passion. My poor mother would just have her head in her hands, hoping we’d move on to another area of interest. So, you can imagine our old farmhouse was quite raucous.”

Dr. Parsons continued: “Everything in high school was gender-based, and part of that was a function of the era. This was all before Title IX, with no funding for girls’ athletics. So, whatever sports we played were through clubs or things we set up ourselves. When I thought about going to college, the first thing I thought about was I would love to go to a place where women were celebrated, and there would be resources to support women to become self-sustaining. Math was my favorite subject, and I always thought I might incorporate it into my future life. I also knew that college was inevitable, which was not at all true for most of the girls where I grew up. In my family, everyone had gone to college, beginning with my great-grandfather who was a state legislator. Both my parents had graduated from Cornell, as had several close relatives, and I think my one streak of rebelliousness in my childhood was deciding not to go to Cornell,” she explained.

Her rebellions streak led Dr. Parsons to the newly formed Kirkland College, a small women’s liberal arts school founded on a progressive model. “It was in the 1960s when the new college movement focused on thematic learning and on self-designed majors. I liked the unconventional nature of it. I also liked the fact that I had been awarded a Regents scholarship by the State of New York and was able to use it to cover nearly all my college expenses, which was a very sweet deal,” said Dr. Parsons.

An Eye-Opening Journey Abroad

Before embarking on college, however, Dr. Parsons seized an opportunity to spend her senior year in high school as an exchange student in Argentina, becoming the first girl from her part of the state chosen for this program. She was sent to the Pampas in Argentina to live and work on a large cattle ranch with frequent trips to Buenos Aires.

“It was truly the adventure of a lifetime riding bareback or on a sheep-skin in lieu of a saddle, rounding up the cattle over thousands of acres for vaccination or branding. Our family farm felt puny by comparison. The great takeaway from my year in Argentina was that it was the first time I had emerged away from my family. I also lived with families who spoke no English, so out of necessity, I eventually acquired quite a competency in Spanish,” she shared.

Later, as a college junior, she spent the academic year in Madrid. There, in addition to taking classes, she worked as a research assistant to the national historian of Spain, who at the time, was writing a book about foreign intervention in the Spanish Civil War. “We worked at the National Archives under the watch of the Spanish Guardia Civil, which was a very oppressive environment, but the research was fascinating. For my undergrad thesis, I applied a type of theory called conflict theory to understand press censorship in Argentina during the Peron dictatorship. I got access to the Library of Congress and to the Sterling Library at Yale, where I found microfiche for three different newspapers and performed content analysis over this 11-year period, which was completely fascinating,” she said.

After attaining her BA at Kirkland College, Dr. Parsons entered a Master of Regional Planning degree program at Cornell University, where she was awarded a full fellowship under the Foreign Language and Area Studies program and met her husband. “I moved to New York to be a health systems analyst and landed a job at a large management consulting firm doing actuarial analysis on the rate structure of this newfangled program called health maintenance organizations.” From there, she moved to serve as a project manager of a large cost containment project, which involved in-depth interviews—in Spanish—with participants in the program. While in that role, her supervisor, Chair of Cornell’s Department of Public Health, often remarked that her interest in the patients’ stories struck him as not typical for an economist. “He sent me uptown to Columbia to meet with the director of the postbac-premed program. It began my very long detour to medicine,” she remembered.

Asked about early mentors at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, Dr. Parsons replied: “I was completely inspired in pediatrics by the former chief of Harlem Hospital, Margaret Heagerty, who tackled head-on the issues of drug addiction and HIV in children. I found her inspiring.”

A Push in the Right Direction

Following her internship, Dr. Parsons did her residency training in pediatrics and fellowship training in pediatric hematology/oncology at the Children’s Hospital Boston/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“As a resident, I worked closely with our physician-in-chief, David Nathan, and our program director, Fred Lovejoy, who have been lifelong mentors and friends. I was also Dr. Nathan’s Chief Resident; it was an incredible year working with him,” said Dr. Parsons. “In retrospect, I doubt I would’ve gotten into medicine if somebody hadn’t pushed me in that direction.”

According to Dr. Parsons, she was drawn to pediatric hematology/oncology by the combined challenge of science and the psychosocial context of the care model. “Everything about the field felt riveting, and I had the good fortune to stay at Boston Children’s and train in the combined Dana-Farber and Boston Children’s Program, where I had magnificent co-fellows who remain among my closest friends. Our clinical mentors were amazing—Dr. Howard Weinstein and Dr. Eva Guinan in stem cell transplant; Dr. Stephen Sallan and Dr. Holcombe Grier in oncology; and Drs. Orah Platt, David Williams, Sam Lux, and Ellis Neufeld in hematology, with David Nathan being at the center as my career-long mentor,” she commented. “At the end of fellowship, our family grew with the birth of our son. Thirty years later, he enriches our lives in every way.”

Dr. Parsons continued: “I served as an attending physician on the Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) service at Children’s Hospital Boston for 12 years and as attending on the adult HSCT service at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for 6 years. In 2003, I brought my research funding initially from the American Cancer Society and then the National Cancer Institute with me to Tufts Medical Center, where I now run an Institute in Health Outcomes. Over the past 20 years, I have incorporated patient-reported outcomes in many clinical trials for children, adolescents, and young adults.”

Research on Survivorship

Asked for a snapshot of her current work, Dr. Parsons commented: “I have moved away from direct inpatient care in the acute transplant setting and am more focused now on survivors of cancer. About 10 years ago, I received an incredible gift from a family whose son had died of cancer, and they wanted to set up a program in his memory. The focus of our program is comprehensive survivorship care of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. I work in that clinic 1 day a week. We see patients who are survivors of childhood cancer as well as survivors of young adult cancer, coordinating their often complex care across specialists and clinics. The rest of the time, I run my research, which is currently funded by the National Cancer Institute and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

“I have a very committed and talented research staff that works closely with me. I also serve as the Scientific Chair of cancer care delivery research for the Children’s Oncology Group. In this role, I work with faculty around the country in developing new studies to focus on access, quality, and outcomes of cancer care, in both academic and in community oncology settings.”

Closing Thoughts on Oncology

“The amazing thing about being an oncologist is that I have never spent a day being bored,” Dr. Parsons stated. “I feel like my brain is constantly expanding, constantly stimulated by the advances across the entire spectrum of basic science.”

She continued: “I’m not a cancer biologist, but I find the work people are doing to be riveting. I don’t do experimental therapeutics, but I find that work fascinating. The richness of the specialty is much more profound than I even expected.”

Dr. Parsons shared her excitement about collaboration and its potential. “We have an international collaboration of more than 70 investigators right now that is the basis of my currently funded R01. We’ve pulled together data from around the world (seminal clinical trials and prominent registries) to develop better clinical prediction tools to help patients and doctors make decisions in the era of novel therapy and the long-term consequences of our treatments,” she said.

She added: “Part of this is built on my fascination with math and modeling. But the potential to help patients and providers make these difficult decisions is very exciting.”

Reading and Nature Walks

What does a super busy oncology professor and health-care researcher do to decompress? “I listen to music and still sing, not professionally, but to my radio or CD player. I love to read and walk in nature. I just finished reading Louise Penny’s series on Chief Inspector Gamache, which I would strongly recommend. I also recently read The Fountains of Silence by Ruta Sepetys, which was evocative of my studies in Spain. When I am not working or reading, I love to be outside. Most of my nonworking time during the pandemic was spent walking through nature preserves, which I found to be both physically and mentally replenishing. I have an incredibly close family and love to spend time with them. Before the pandemic we traveled together extensively. We all look forward to getting back on the road.”