Success in tennis demands precision timing, extraordinary hand-eye dexterity, and commanding mental and physical vigor. According to Harold P. Freeman, MD, the discipline and skills he learned on the tennis courts at an early age stood him in good stead during his remarkable life’s journey.

“My parents were accomplished tennis players who first met on the courts and married 2 years later. When I was five, my mother took me and my brothers to the tennis courts, instead of the playground. The discipline of trying to perfect my tennis game instilled a drive in me that carried into my career as a surgeon,” said Dr. Freeman, who came of age on the courts of Washington, DC, a time of bitter segregation in which he could not quench his thirst after a long set of tennis at a water fountain used by his White opponents. His skills would carry him to being invited to compete in the U.S. National Tennis Championships in the mid 1950’s.

Harold P. Freeman, MD

TITLE: President and Chief Executive Officer of Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute

MEDICAL DEGREE: MD, Howard University College of Medicine

ON HIS MORE THAN 30 YEARS AT HARLEM HOSPITAL: “From day one, it was an eye-opening experience. Most of the patients with cancer coming into Harlem Hospital had advanced disease. One socioeconomic pattern was clear to me: All the patients were poor and Black. To help the community, I needed to disentangle the meaning of race and poverty as it related to health-care outcomes.”

Hard Work and Education

Dr. Freeman was born on March 2, 1933, in Washington, DC, to Clyde and Lucille Freeman. Education and culture were long-held features in the Freeman family. Dr. Freeman’s great-granduncle, Robert Tanner Freeman, graduated from Harvard University in 1869 with a doctorate in dentistry, a first for a Black person, and his cousin, Robert Weaver, was former Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Lyndon Johnson. Dr. Freeman’s father, Clyde, earned a law degree at the age of 40, working multiple jobs to pay for his tuition. He would die of testicular cancer when Dr. Freeman was 13, which affected Dr. Freeman’s later career path.

“When my father died, even though I was still a young boy, I saw the underlying cruelty of cancer that took my father away, which, of course, was devastating on many levels. My mother, who was a schoolteacher, had to shoulder the emotional and financial burdens of raising our family. It was difficult, but she was a determined woman who never doubted that her children would go on to higher education,” recalled Dr. Freeman.

Dr. Freeman attended Dunbar High School, which was created after the Civil War to offer a high-quality education to Black students. “Dunbar attracted students with high educational ambitions as compared with other schools in the system, and the teachers themselves, all of whom were Black, were extraordinary. Many had advanced degrees but ended up at Dunbar because they couldn’t go elsewhere in the segregated school system. So, in effect, a double negative turned into a positive, and I received a world-class education that gave me a foundation for my later work,” he said.

Dr. Freeman continued: “Although during my formative years I had a good education and a strong sense of family and community, I was also deeply affected by segregation and how it changed my perspective of society. For instance, I was a competitive tennis player, but my potential was limited because I couldn’t compete against White tennis players. In addition, other injustices during segregation planted a seed that would later bloom during my career as a surgeon confronting social injustice.”

A Scholar and a Gentleman

After graduating Dunbar High School at the top of his class, Dr. Freeman received a scholarship to attend Catholic University in Washington, DC, where he excelled in academics and sports. He starred on the University’s tennis and basketball teams and garnered the Harris Award for Outstanding Scholar, Gentlemen, and Athlete.

“During my undergraduate work at Catholic University, I was exposed to the deeper philosophical thinking of Plato, Socrates, Thomas Aquinas, and others, which further shaped my understanding of the world around me. At that time, I was also influenced by the writings of Albert Einstein, whose scientific theories, in short, gave me a deeper understanding of the value of interpreting human behavior from different perspectives, such as through the lens of race, which would later inform my medical work in poor Black communities,” said Dr. Freeman.

Dr. Freeman had originally thought about pursuing a career in teaching, but his mother encouraged him to become a doctor, a profession she felt better suited his talents and sense of social justice. Although Dr. Freeman had an exceptional academic record, he was accepted only to the historically Black Howard University College of Medicine. After earning his medical degree from Howard University, he completed a residency in general surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital, which is now Howard University Hospital.

Dr. Freeman’s skill as a surgeon began to attract notice. In 1964, he accepted an advanced residency position at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) in New York, where his career as an oncology surgeon was further established. “Memorial was a terrific opportunity, a place where I honed my skills working with some of the world’s best oncologic surgeons. But I also was being exposed to the inequities faced by poor people trying to navigate a perplexing system. And the realization that poverty was the root cause of many health-care inequities would soon trouble me into action,” said Dr. Freeman.

Leaving MSK for Harlem Hospital

In 1967, after 4 invaluable years at MSK, Dr. Freeman joined Harlem Hospital, for what he projected as a temporary assignment. Instead, he remained on staff at the hospital for more than 30 years.

“From day one, it was an eye-opening experience. Most of the patients with cancer coming into Harlem Hospital had advanced disease. Women walked in with ulcerated breasts, and surgery offered no answer for them. They often went to the emergency room, where they were turned away. Most had no personal physician and no means to pay. One socioeconomic pattern was clear to me: All the patients were poor and Black. To help the community, I needed to disentangle the meaning of race and poverty as it related to health-care outcomes,” said Dr. Freeman.

Soon after, Dr. Freeman said he began to grapple with larger questions: “Are these people with cancer dying because they’re Black? Or are they dying because they’re poor? Or are they dying because of some combination of being Black and poor? That became the critical question: to try to fix a chronic social issue, you need to know its underlying components. In other words, if people were dying because of a genetically driven pathway, the approach to fixing it would be different than if poverty was the main driver. So, I needed to understand the issue at its fundamental level,” he explained.

For Dr. Freeman, the poor-outcomes issue faced by the population of Harlem soon crystalized in one woman’s journey, an allegorical patient with breast cancer whose journey was emblematic of the broken system itself. Let’s call her Destiny. She told Dr. Freeman that she had gone to the Harlem Hospital emergency room 2 years before with a lump in her breast, waiting patiently for 6 or more hours before seeing a doctor. Although he was polite, he told Destiny she was in the wrong place, stressing that a breast lump wasn’t an emergency; instead, she needed to go to the Medicaid office (about 100 blocks south of Harlem Hospital at the time), receive a Medicaid card, and make an appointment at the clinic (not the ER). Destiny was a poor, single mother of three, who had a daily struggle to provide food, clothing, shelter, and protection for her kids in Harlem, which in the 1970s was rife with street crime. For Destiny, the health-care system she’d entered posed no solution to her medical issue.

“For that woman, the process being recommended for her was more painful than the painless lump, which was not bothering her except that it was there. And this woman’s story was the story of Harlem’s poor residents’ writ large. By this time, I was Director of Surgery at Harlem Hospital, and I set up a free clinic on Saturday morning at 9:00 AM in which people could walk in without registering into the hospital. It began to work, until I had issues with the hospital’s administration, which was concerned—and rightly so—that the walk-in clinic could run into legal issues given the patients did not register with the hospital. Finally, the hospital Vice President, a Black woman, helped me convert the free clinic to one that was within the hospital system. That was the big step forward,” said Dr. Freeman.

Connecting Life’s Currents

Dr. Freeman described this period as having different yet concurrent streams in his life, connected into a single river, giving more control of the positive flow. Governor Hugh Carey’s wife died of breast cancer in 1974, which had affected him deeply. In response, he set up a high-level committee to advise him about a course of action in breast cancer prevention and treatment in New York State.

“I had published a paper about the death rate from breast cancer in Harlem that got quite a bit of attention,” he said. “I was called to testify before the committee, which resulted in the governor funding two clinics in Harlem, which offered free breast and cervical cancer screenings under the auspices of MSK. By 1988, these clinics had examined more than 15,000 women. It was a true success in public health,” said Dr. Freeman.

Because of his notable work in Harlem’s underprivileged populations, Dr. Freeman was elected to the board of the American Cancer Society (ACS), as National Director at Large. “Dr. LaSalle D. Leffall was President of the ACS in 1978, the Society’s first Black president. He had started a committee called Cancer in Minorities after holding a meeting in Washington on cancer in Black Americans. After several high-level discussions, I was chosen to lead a committee of select scholars from around the country on a 2-year study. The study findings were published in 1986 with the title Cancer in the Economically Disadvantaged; we concluded that the principal reason Black people were dying of cancer at higher rates than their White counterparts was because they were poor,” said Dr. Freeman.

In 1989, Dr. Freeman would become National President of the ACS, the second Black President of the Society. He made special note of the late Arthur I. Holleb, MD, a renowned surgical oncologist at MSK who helped him on his road to becoming a board member and President of the ACS. During this time, Dr. Freeman was also appointed to the position of Associate Director of the NCI and Director of the NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities.

Dr. Freeman related: “The principal activity I carried out during my year as ACS President was heading the national hearings on cancer in the poor, which I led in seven American cities, hearing the testimony of poor people, of all

races, who had cancer. This committee concluded that the experience of poor people with cancer is they meet barriers. Poverty is a proxy for lack of education, inadequate housing, insufficient nutrition, and concentration on day-to-day survival as opposed to long-term or preventive care. It is also a proxy for barriers to medical care. Poor people may have as many encounters with the health-care system in a year as do middle-class people, but these encounters tend to be for symptomatic rather than preventive reasons,” according to Dr. Freeman.

Patient Navigator: A New System to Help Patients With Cancer

As Dr. Freeman reviewed the breadth of his work and scholarship examining the relationship of poverty and poor health outcomes, it became clear that poor people with cancer needed professional assistance to make their way through the dizzying medical maze they encountered. He continued: “Maybe we could navigate people through the barriers. That’s how I coined the phrase and created the concept of ‘patient navigation.’”

In 1990, Dr. Freeman started the first patient navigation program at Harlem Hospital in the same clinic that met on Saturday mornings. “The program was supported by a small grant from the ACS, and it grew from there,” he said. “I was fortunate to have the opportunity to present on patient navigation at some high-level organizations, such as the National Cancer Institute [NCI], when I became Chairman of the U.S. President’s Cancer Panel and the first Director of the NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. I had the chance to speak to the nation.”

Dr. Freeman noted another milestone in patient navigation. In 2005, President George W. Bush signed the Patient Navigator Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Act. “That was a big political turning point based on the model that came out of Harlem,” said Dr. Freeman. Then, in 2015, the American College of Surgeons mandated patient navigation as a standard of care to be met by all cancer centers. Moreover, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has patient navigation requirements as well, such the use of patient navigation to assist uninsured patients to gain insurance through the exchanges.

A History Lesson

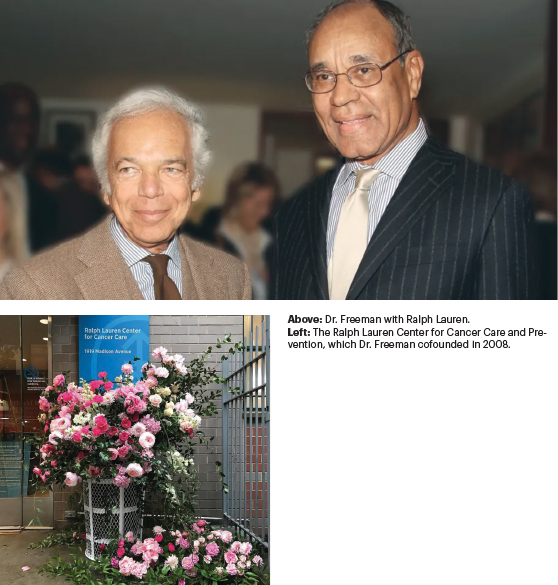

Along with his role at Harlem Hospital, Dr. Freeman was President and Chief Executive Officer of North General Hospital, a 200-bed, minority-operated community teaching hospital located just 10 blocks from Harlem Hospital, Harlem’s sole nonprofit medical institution. And, in 2003, Dr. Freeman took the helm of the Ralph Lauren Center for Cancer Care and Prevention in Harlem, a position he held until his retirement.

During his illustrious career, Dr. Freeman received numerous awards and prizes, among them the Lasker Award for Public Service in 2000. This honor was for enlightening scientists and the public about the relationship among race, poverty, and cancer. In 2015, Dr. Freeman was named a “Giant of Cancer Care” by OncLive.

Asked about his current activities, Dr. Freeman responded good-naturedly: “Well, I don’t play tennis anymore. My groundstroke isn’t what it used to be.” Then, he mentioned his interest in genealogy. “There’s a lot to be learned from digging back in the past. I’ve discovered an ancestor named Lewis who was born in 1775, a year before the Declaration of Independence was drafted and signed. Lewis was born a slave but was a free man before the age of 25. He became an extensive landowner, in Chatham County, North Carolina. Lewis had a son named Waller who was a slave because his mother was a slave. Lewis eventually bought his own son out of slavery. Think of it. So that’s what I’m doing now, tracing my ancestry back to its roots, which is America’s roots, too, also her history.”