Community practices have long been a keystone of our nation’s oncology care delivery system by allowing patients with cancer to receive specialized treatment near their homes and places of business. Innovative clinicians in the community setting are also leading efforts to create a more efficient and equitable value-based delivery system.

“We need to transform our care delivery system,” said Kashyap Patel, MD, Chief Executive Officer of Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates (CBCCA), an independent oncology practice serving diverse patient populations in rural areas, with locations in Rock Hill and Lancaster, South Carolina. “In addressing a diagnosis of cancer, we run the risk of reducing a human being to a piece of aberrant tissue. We forget this patient is a husband, wife, friend, lover, brother, sister, cousin. If instead of using a fragmented approach, we define patient-centered care as holistic care, with human beings in the center, and fix aberrant tissue as a part of the ecosystem, rather than just focusing on cancer tissue, we can serve patients better,” he proposed.

Kashyap Patel, MD

TITLE: Chief Executive Officer of Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates

MEDICAL DEGREE: MD, Gujarat University

ON HIS PILOT PROGRAM CALLED NO ONE LEFT ALONE IN SOUTH CAROLINA: “Policy alone can’t solve the inequities of cancer care. Community practices should be ready to address inequities as part of future value-based models, and doing so will help practices succeed and keep patients in community clinics.”

A Bollywood Film Leaves a Lasting Impression

Dr. Patel was born in Ahmedabad, a bustling city in the Indian state of Gujarat, which is situated along the Sabarmati River. “I grew up in what would be considered a standard middle-class family,” shared Dr. Patel. “My father was an engineer, and there were really no doctors in the family to inspire my own interest in medicine. But back in 1970, when I was 9, I went to see a movie called Anand, in which a doctor treats a patient with lymphoma. The patient, named Anand, upon learning of his impending death determines to use the time he has left to the absolute fullest. The film left me inconsolable; I couldn’t stop crying. I really admired the hero, and my father told me that when I grew up, I should become a doctor and learn how to treat that same disease,” he said.

Dr. Patel continued: “That experience stayed with me for a while, but like all things when you’re young, eventually faded away in the hecticness of youth. When I was 16, I began to seriously consider pursing a career in engineering, as there were a lot of exciting things happening in the field. But my father, himself an engineer, intervened and reminded me about Anand and how much it had affected me. At that point, I dropped the idea of engineering and decided to go to medical school. After finishing my prerequisites, I entered Gujarat University in 1984 to study medicine and received my medical degree in 1987.”

During the 1980s, Dr. Patel noted, neurology and cardiology were the specialties drawing the most attention among ambitious young doctors fresh out of medical school. “After finishing my MD, I went to do a neurology fellowship in Bombay, at the Bombay Hospital & Medical Research Center. However, when I got there, the administration said there was no paid position, so I’d have to moonlight while doing my fellowship. Well, I ended up getting a moonlight position in a hematology/oncology clinic, and when all the memories from the movie Anand came flooding back over me, that was when I made the commitment to become an oncologist,” said Dr. Patel.

Looking for More Experience

After completing a 2-year training program in Bombay, Dr. Patel returned home to Ahmedabad in 1989 and started a private hematology/oncology practice. “My practice was going well, but I felt a sense of inadequacy in my oncology training. So, I applied for a hem/onc scholarship in the UK and was accepted by the University of Manchester. I spent 4 very productive years there and eventually landed a junior faculty position in Scotland. However, during a meeting where I was presenting a poster, an oncologist I met said I should consider relocating in the United States, where he thought I’d find more opportunity to grow my career.”

However, Dr. Patel was concerned about entering the United States on a visa, which was an ongoing process of re-registering. “Because of my publications and other work, however, I was given an employment-based immigration first preference EB-1 visa, which is issued to a noncitizen of extraordinary ability. I could immigrate to the United States with my whole family, even if I didn’t have a job lined up,” explained Dr. Patel. “It was quite an honor, and I have always appreciated the opportunity I was given to become part of the medical community in the United States.”

When Dr. Patel arrived in the States, he immediately signed on to a residency program at Jamaica Hospital in Queens, New York. Residency on the oncology clinic at the busy city hospital was a good learning experience for Dr. Patel, but his American oncology journey had just begun.

Dr. Patel related: “In 1999, I left Jamaica Hospital to do a hem/onc fellowship at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, where I became involved in publications and research, particularly the early studies in immunotherapy in melanoma. So, I did some very interesting work and presentations, and I was even offered a faculty position. However, by nature I am a people person, and I was concerned I’d be unfulfilled in academic oncology, so I began looking for a position in a community practice. Then, out of the blue, a friend I’d gone to med school with called me after almost a decade and suggested I look at a group practice he knew in South Carolina. Honestly, I knew nothing about South Carolina, but my friend said it was a beautiful place to practice, and the people and community were great,” he commented.

On a whim, Dr. Patel traveled to Rock Hill, South Carolina, to meet with the head of the Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates. “I met with Dr. Welsh, and we immediately clicked, like we’d known each other for years. They hadn’t planned to hire a new oncologist, but he said I looked like a good fit for the practice, so he actually took a pay cut to help create a new position for me on the staff. And from there, as they say, the rest is history,” he noted.

Soon into his new job, Dr. Patel became interested in the politics and challenges faced by practitioners in community oncology, so he began becoming involved in the South Carolina Oncology Society (SCOS). “I became an SCOS board member, and then the leaders saw my potential. I was asked whether I’d like to get on the leadership pathway that would put me on track to become SCOS President in several years. I agreed and began doing a lot of local legislative work and eventually became SCOS President in 2014,” he said.

Along with his involvement in legislative affairs on the state level, Dr. Patel is President of the Community Oncology Alliance (COA). In addition, he has been Chair and a trustee for Clinical Affairs, the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), and a member of the Clinical Practice Committee for ASCO and the National Committee for Quality Assurance. He has been an advisor for the large payers including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (South Carolina) Palmetto GBA. He has received the Living the Mission Award from the NCODA and the Outstanding Achievement award by the SCOS. He is also a nominee for the Ellis Island Medal of Honor for the current year.

Open-Door Policy

Dr. Patel stressed that the Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates has never turned a patient with cancer away because of financial reasons; their door is open to all who need care. “From day one of my oncology journey here, I have never looked back or regretted a single moment in this great profession,” said Dr. Patel.

Asked about evolutions in cancer care that bring more value to the ecosystem, Dr. Patel commented: “For one, the value-based care model taught us how to define the way we practice oncology and improve the patient experience. For instance, we can reduce costly and unnecessary hospitalization and ER visits by providing more access to care for patients.

Dr. Patel shared his experience with a 40-year-old single mother with breast cancer. “If she has a fever on a Friday night, we can get her the right access to urgent care. If we did not have care coordination after hours, she would end up in the ER for 12 hours or so, and her three kids at home will not understand what’s happening to them. She could be hospitalized and lose days of work.”

Dr. Patel continued: “To that end, we realized we also needed an open-door policy, so we let our patient population know that if they need help with anything, they can walk in between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM every day. It was so successful that we began coming in on weekends for a few hours. Moreover, we partner with local urgent care facilities and give them access to our EMR [electronic medical record] system ona case-by-case basis; this way, if our patients must go to the urgent care, they can be triaged and have all their blood work and vitals delivered to us—so we do a partnership of care. So far, we have seen a 30% reduction in hospital visits since we initiated these steps. We even published brochures and detailed instructions to patients for the same.”

Furthermore, Dr. Patel is piloting a program called No One Left Alone (NOLA) in congressional district five of South Carolina to bring access to the right care, including precision medicine, to patients despite their socioeconomic status rather than putting the burden on patients to coordinate and travel for care. “Policy alone can’t solve the inequities of cancer care. Community practices should be ready to address inequities as part of future value-based models. Doing so will help practices succeed and keep patients in community clinics. I’ve been collecting data to quantify gaps in care such as access to clinical trials; the goal is to create a playbook of sorts that evaluates and offers solutions to these access issues among the underserved. This is one of my current projects and something I am passionate about,” he shared.

Mortality Issues

Dealing with the existential crisis often associated with impending death is a prominent part of the cancer care continuum, an area of study and reflection in which Dr Patel has become an expert in palliative care and end-of-life issues. In that role, he teaches other physicians how to answer the difficult open-ended questions of dying patients. “No one prepares doctors to have these conversations with patients who have cancer and are dying, but it is vital to address. Even as a patient walks toward that horizon, he or she wants to make the most of life and accept death with grace,” he said.

In his book Between Life and Death: From Despair to Hope (to be reviewed in an upcoming edition of The ASCO Post), Dr. Patel introduces us to Harry, who after a full and adventurous life is diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer. As Harry faces his mortality, he leans on Dr. Patel to help him cope with the unanswered questions in his life and his growing fear of death.

“In the book, I tried to help patients with cancer prepare for the journey beyond life, along with aiding their families in coping with the loss and helping them all find closure in the time God has left them,” explained Dr. Patel.

‘Everyone Has a Story’

What does a busy leader in community oncology do to decompress? “When I get home, I meditate on my porch, which overlooks a golf course,” Dr. Patel commented. “There’s an eagle that often flies into the area while I’m meditating. I also read nonfiction and watch a lot of The Great Courses on the Web. I’m also a people person, and my son and his wife live in a separate part of the house, so my wife and I spend time with them. Finally, I also like to have a glass of Pinot Noir at at two of my favorite places: Zinicola Wine Company, where I meet people and talk. I like people. Everyone has a story.”

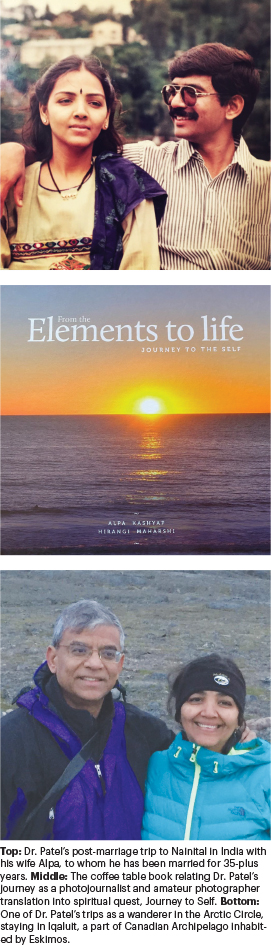

He added: “I am an avid photographer (have had one man shows, and every other year, I wander in the wilderness of various national parks and take photos). I have also published a coffee table book documenting my journey as a photographer and a photojournalist—From Elements to Life: A Journey to the Self.