The term “head and neck surgery” had little meaning until the 1940s, when it was used by groundbreaking surgeon Hayes Martin, MD, in one of his publications. Dr. Martin was then Chief of Head and Neck Services at Memorial Hospital, later renamed Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), where the new field of head and neck cancer surgery came of age. Over the ensuing decades, dedicated surgeons at MSK, such as Jatin P. Shah, MD, FACS, the Elliot W. Strong Chair in Head and Neck Oncology, have dramatically improved survival and quality of life for patients with head and neck cancer.

Jatin P. Shah, MD, FACS

TITLE

Elliot W. Strong Chair in Head and Neck Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, Maharaja Sayajirao University

ON HIS CAREER PATH

“There is an American phenomenon about one’s career: you go someplace, soak up what you can, and move on. There is some virtue to that philosophy, but the other side is that you can probably get more out of yourself by staying in one place and nurturing your environment. At MSK, I had all the tools necessary to build a robust career and a network of world-class colleagues. I never saw a reason to leave and start over. I never looked back, from day one.”

Father Knows Best

Dr. Shah was born in India; his father was a high school principal who guided his children’s education. “My brother became an engineer, and my sister became a psychologist. At that time in India, the father of the family essentially chose his children’s career paths for them. In educated families like ours, law, engineering, and medicine were considered the best professions. My father decided that my older brother should go into engineering, and I should pursue medicine and become a surgeon. There wasn’t much room for discussion. It was more like giving a salute and saying, ‘Aye, aye, captain!’ Obviously, his decision worked out well for me,” said Dr. Shah.

After graduating high school, Dr. Shah went to the Medical College of Maharaja Sayajirao University in Vadodara, where he did his basic training in general surgery and received his master’s of surgery degree. “However, my brother and sister had relocated to the United States and had convinced my parents to join them in 1964, so after I completed my 4 years of surgical training at the Medical College, given that nobody was left at home, I also migrated to the United States,” said Dr. Shah.

Dr. Shah did a year of surgical research program at the Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia, where he worked with John Howard, MD, Chairman of the Department of Surgery. During his time at Hahnemann, Dr. Shah passed his Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates examination and applied for a surgical residency at MSK. “The primary reason I decided to go into surgical oncology, as opposed to cardiac surgery for instance, was that my father had died of lung cancer in 1965, and I wanted to pursue a career that could better the lives of people diagnosed with cancer,” said Dr. Shah.

He continued: “After a year’s residency in general surgical oncology at Memorial, I stayed on for a 2-year surgical fellowship. I became attracted to head and neck surgery, largely because of the challenges within that very difficult part of the body. For example, if I perform surgery on your heart, you can put a shirt on, and no one will notice that. But if I resect even a 1-cm squamous cell carcinoma on your face, the whole world sees the result. How we see, hear, smell, talk, swallow, and express ourselves is all concentrated in the head and neck. Preservation or restoration of these functions was a challenge. So, I wanted to advance the surgical field in preservation of form and function. I contacted the Chair of Surgery, Edward J. Beattie, Jr, MD, and explained that I was interested in head and neck cancer. After he conferred with Elliot Strong, MD, Chief of the Head and Neck Service, I was recruited to the faculty at Memorial in 1975.”

Work in the Lab Leads to a Surgical First

After assuming a faculty position, Dr. Shah spent considerable time in the laboratory, teaching himself microsurgery. In 1978, Dr. Shah introduced myocutaneous flaps and free jejunal flaps, which opened the door to additional microvascular reconstruction techniques in head and neck surgery down the road. “Then, in 1978, I organized a week-long CME course, “Current Concepts in Surgical Oncology,” which had never been done at Memorial. As my career progressed, I explored opportunities on the national stage by creating a relationship with the Society of Head and Neck Surgeons and began developing teaching seminars at the American College of Surgeons Annual Clinical Congress, which I led from 1982 to 1990.”

Growing Reputation

As Dr. Shah's reputation within the surgical oncology community grew, so did his frequent-flyer miles, as he presented lectures at symposia across the world. After a presentation in Singapore, a prominent Scottish head and neck surgeon, Arnold Maran, MD, impressed by Dr. Shah’s lecture and his high-quality surgical pictures, suggested he write a comprehensive book that would provide practical coverage of the latest surgical techniques and multidisciplinary therapeutic approaches for head and neck cancer. “That conversation inspired me to write Jatin Shah’s Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology, which was the first textbook in the field. It is now in its fifth edition, and, at the risk of beating my own drum, it has been voted as the best book on head and neck surgery by several international organizations,” said Dr. Shah.

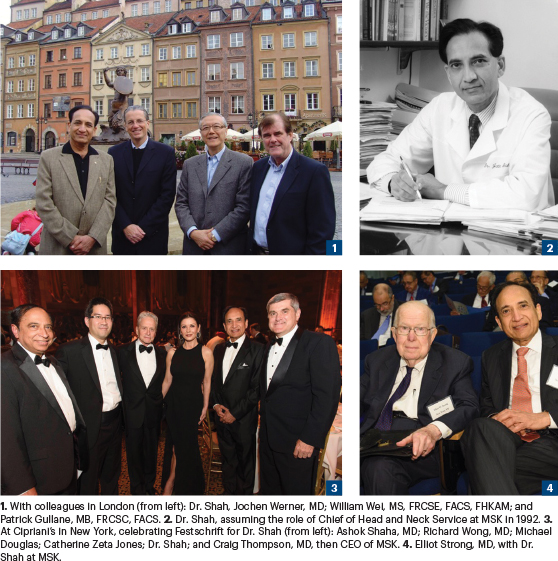

Concomitant to the publication of his highly regarded textbook, Dr. Shah was a rising presence in the Society of Head and Neck Surgeons. “By 1986, I was the Secretary of the Society and felt we needed to take our mission onto the international stage. Remember, this predated the Internet, so communication was all by snail mail. I would draft and post a letter and expect a reply in about 2 months. Nevertheless, my efforts paid off, and I received unanimous support from key international leaders in the field, which culminated in the formation of the International Federation of Head and Neck Oncologic Societies (IFHNOS). One of our major goals was to improve the training of surgeons and increase the number of well-trained head and neck surgeons; to that end, we created the Global Online Fellowship (GOLF). In the past 6 years, we have certified 285 surgeons from this fellowship program. Candidates for the fellowship come from 45 countries, including the United States, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, India, China, Russia, Spain, Australia, and many others,” said Dr. Shah.

Assuming a Leadership Role

In 1990, Elliot Strong, MD, Chief of the Head and Neck Service at MSK, decided to step down, and a search committee convened to find his replacement. “Six candidates were interviewed: four international, two national, and one internal, which was me. In 1991, after an exhaustive review process, I was selected as Chief of Head and Neck Services. Now, my position changed dramatically from surgeon to surgeon administrator, which meant I was charged with growing the Head and Neck Service by carefully selecting surgeons and recruiting them to the service. I also had to expand our clinical and translational research efforts,” said Dr. Shah.

“When I took charge of the service, we had 3 surgeons; over 8 years, we built it up to 11 highly regarded head and neck surgeons. When I became Chief, our research program was barely existent. So, I recruited two faculty members with interest in basic research and supported the development of their own laboratories, both of which blossomed. During my tenure as Chief, I also trained 106 fellows, of whom about 80% went on to stellar academic careers. So, over the course of my career, I believe I helped give head and neck cancer surgery a global footprint, and that mission continues,” said Dr. Shah.

Passing the Scalpel

During his 23 years as Chief, Dr. Shah became a world leader in the field of head and neck cancer, and the service continued to be a center of excellence in patient care, research, and education. In 2015, Dr. Shah stepped down as Chief to dedicate more time to educating the next generation of head and neck surgeons, both within MSK and internationally through the Online Head and Neck Fellowship Program of the IFHNOS.

Asked about his decision to step down from his surgical duties, Dr. Shah replied: “After 45 years of nonstop operating, I decided to quit performing surgery while I was still flying high, so to speak. It was 9:30 PM on my last day in the operating room, and I took my gloves off and said goodbye to the nurses. It was the right time, and I have no regrets. That said, along with my current administrative and leadership duties, I still see patients in the clinic and pass them on to my junior faculty. I teach fellows regularly, which I find enormously rewarding. I write and used to travel like crazy until this past year, but hopefully it will begin again.”

It is common practice for academic oncologists to make several moves over the arc of their career; however, Dr. Shah was recruited to MSK in 1974 and never left. “There is an American phenomenon about one’s career: you go someplace, soak up what you can, and move on. There is some virtue to that philosophy, but the other side is that you can probably get more out of yourself by staying in one place and nurturing your environment. At MSK, I had all the tools necessary to build a robust career and a network of world-class colleagues. I never saw a reason to leave and start over. I never looked back, from day one,” said Dr. Shah.

Passion Is Key

What advice would Dr. Shah give to young fellows still searching for answers about their career paths? “Your profession should be your passion. If it is, you never feel like you’re working. When Picasso was putting paint on a canvas at 2 o’clock in the morning, he wasn’t working overtime; he was in ecstasy with his chosen career. If you love what you do, you will never look at the clock and will never retire. My office at MSK is my home, where I spend 8 to 10 hours a day. If you truly love what you do, you won’t suffer burnout.”

Dr. Shah is truly a citizen of the world, and once the pandemic-imposed restrictions are lifted, he plans to decompress by traveling to far-flung corners of the world. “I love to travel and meet people from other parts of the planet, even the most remote, and learn about their experiences. We in the United States are blessed in that, for the most part, we live in a gilded world. Everything is here; all you have to do is get up in the morning and go to work. So many millions of people around the world wake up and wonder how they are going to feed their children. I think it’s important to understand how fortunate we are in this country.”