There are few, if any, more difficult clinical challenges than pancreatic cancer, a disease that continues to confound the oncology community’s quest for cure. Yet, incremental progress and unflagging optimism drive the way forward, thanks to the researchers and clinicians who have dedicated their careers to this complex disease, such as Douglas B. Evans, MD, FACS, Chair of the Department of Surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Sports and Medicine

Dr. Evans was born in Providence, the capital of Rhode Island and one of the oldest cities in the United States. “My father was an outstanding athlete. He played football at the Division I college level and worked part-time at the YMCA. After college, he continued working for the YMCA, making it his lifelong career. He eventually became the Director of the Old Colony YMCA in Brockton, Massachusetts. Brockton is the hometown of boxing legend Rocky Marciano and other great boxers. My mother, who taught music and grade school, also grew up in Brockton as a second-generation Italian American,” said Dr. Evans.

According to Dr. Evans, he grew up in a typical middle-class environment, spending free time at the YMCA and playing sports—nothing special, other than its small-town sense of stability. “I was lucky to have had two great parents and a wonderful sister. After graduating Oliver Ames High School, I went to Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. Although I loved sports, the natural selection process for athletics skipped a generation, and I didn’t get my dad’s talent. I had the desire, but it didn’t translate to the field or court. The idea of medicine came late in college while taking an introduction to medicine course taught by a radiologist. It was eye-opening, and that’s when I decided to become a physician,” said Dr. Evans.

Douglas B. Evans, MD, FACS

TITLE

Chair of the Department of Surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, Boston University School of Medicine

ON THE HIGHLIGHTS OF HIS CAREER

“I’d say my biggest contribution to the Medical College of Wisconsin has been talent development; we have an amazing department of surgery filled with highly accomplished surgeons in nine clinical divisions. I have been fortunate to continue my work in pancreatic cancer research and treatment with a wonderful team of physicians and scientists across many departments and institutions. We have developed innovative surgical techniques to remove tumors previously considered inoperable and have completed the world’s first clinical trial of personalized medicine in which we based neoadjuvant therapy on the molecular profile of the tumor biopsy.”

A Surgeon Influences a Career Path

Dr. Evans earned his B.S. degree from Bates College and then entered Boston University School of Medicine. “Coming from a fiscally conservative middle-class family, my biggest concern about medical school was cost; I did not want to accrue huge student loan debt. I was lucky enough to get a work-study program where I directed undergraduate dormitories at Boston University, along with a variety of odd jobs. But I soon realized that studying in these dorms was impossible for a variety of reasons, one being the typical antics that define undergraduate college life. So, I ended up getting a part-time job at the Lahey Clinic in Boston, which also gave me access to their library. Lahey, coincidentally, had some amazing surgeons who were at the vanguard of pancreatic surgery, such as John Braasch, MD, PhD, whom I ended up working with during my fourth year in medical school,” said Dr. Evans.

As far as his decision to pursue a career as a surgeon, Dr. Evans cited the influence of Lester Williams, Jr, MD, Chair of Surgery at Boston University at the time. “Dr. Williams was huge, both in physical stature and in his advocacy for medical students and residents. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of surgery and shared it generously. He had an immediate and lasting impact on my career as a surgeon,” said Dr. Evans.

Working With One of the Giants of Pediatric Surgery

After receiving his medical degree in 1983, Dr. Evans matched for a surgical residency at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, New Hampshire. “During the latter part of medical school, I got married to Betsy DeCoste; we had been together since high school. We never planned to go outside of New England, which is one of the reasons why I went to Dartmouth where I had terrific mentors, including my Department Chair Robert Crichlow, MD, who was one of the early surgical oncologists, and Richard Karl, MD, Richard Dow, MD, Jack Cronenwett, MD, and Arthur Naitove, MD,” said Dr. Evans.

During Dr. Evans’ third year in surgical residency, he spent 4 months at DC Children’s Hospital in Washington, DC, working closely with Judson Randolph, MD, who was regarded as one of the giants in pediatric surgery. “One night when I was on call, Dr. Randolph paged me to see a young child being brought to the emergency room. Dr. and Mrs. Randolph were out to dinner when he got a call that a senator’s grandson had an incarcerated hernia, and they would like him to manage this. So, there I was in the operating room with Dr. Randolph and his wife, fresh from the restaurant, performing surgery with one of the most famous surgeons in the country as his wife looked on. At one point, Mrs. Randolph asked how my wife, Betsy, and the kids were doing. To have a senior surgeon and his wife show such concern for a trainee was not common in the 1980s,” said Dr. Evans. “It was quite an experience, and reminds us of the importance of connecting at a personal level with those who we are training—simple acts of kindness can be impactful.”

Plane Ticket to Houston

“Nearing graduation, I was having a difficult time trying to decide between transplant surgery, endocrine surgery, and surgical oncology,”said Dr. Evans. At that time, fellowship opportunities were not organized into a matching process, but instead were a rotating admissions process run by the Society of Surgical Oncology. Dr. Evans went to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for his fellowship interview; however, his life was more complicated than that of most aspiring surgeons. “My wife was pregnant with child number three, and we would need to live in a relatively small dorm next to the hospital. During my interview with Murray Brennan, MD, the Chair of Surgery, I explained that the living situation just wouldn’t work. So, I went back to Dartmouth and told Dr. Crichlow about my dilemma, saying that perhaps general surgery may be the answer as I loved all areas in the field of surgery. He said, ‘Nope, I bought you a ticket; you’re going to Houston to interview at MD Anderson,’” said Dr. Evans, adding, “It goes to show you the enormous value of mentors.”

Dr. Evans’ first fellowship interview at MD Anderson Cancer Center was with the Immediate Past Chairman of Surgical Services, Richard Martin, MD. “It just so happened that Dr. Martin was a third-generation Bates College alumnus, which was a pretty unusual coincidence. He said, point-blank, that I was coming to MD Anderson for my surgical fellowship. However, although my wife Betsy knew it was a great opportunity, she was not thrilled about moving to southeast Texas, which for a woman born and bred in Massachusetts, was a different country,” said Dr. Evans.

A Fellowship Turns Into a Job

Soon after, Dr. Evans began his surgical fellowship at MD Anderson; he presumed he and his family would head back east after completing the 2-year obligation. However, during the fall of Dr. Evans’ second year, Charles Balch, MD, who was Chair of the Department of Surgical Oncology, offered him a job. “The Head of Endocrine Surgery, Robert Hickey, MD, was retiring, and I was offered his place, actually beginning my faculty appointment before finishing my fellowship. Dr. Balch wanted me to focus on pancreatic surgery, as it was underdeveloped at the time. It was 1990, and MD Anderson was just coalescing its now famous multidisciplinary programs in gastrointestinal solid tumor (surgical) oncology and had a very small focus on pancreatic cancer. Dr. Balch really built MD Anderson’s surgical department,” said Dr. Evans.

With the support of Dr. Balch and the partnership of several cancer specialists, such as James Abbruzzese, MD, Tyvin Rich, MD, Bob Wolff, MD, Jeffrey Lee, MD, and Peter Pisters, MD, Dr. Evans grew MD Anderson’s pancreatic cancer program into one of international renown. “In addition to translational research, we focused on a couple very basic observations. First, pancreatic cancer is a systemic disease at diagnosis in almost all patients, even those with apparent localized disease, and the operation to remove it (Whipple procedure) is much greater in magnitude than with colorectal and breast cancer, for example. Moreover, unlike cardiac surgery and solid organ transplant, we remove sections of human anatomy but do not improve the physiology of the patient,” said Dr. Evans.

He continued, “So we focused on treatment sequencing to better select those patients who would truly benefit from surgery. This sounds very simple, but it took about 2 decades for people to appreciate the importance of combining chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery—and in that order. We developed clinical trials for early-stage pancreatic cancer; at the time, almost all trials focused on metastatic disease. We used a multidisciplinary approach (before it was popular) and, unlike other disease site trials that have strict inclusion criteria, our trial accrual was based solely on cross-sectional imaging and performance status at the time of diagnosis. We didn’t give ourselves an A for effort. If the outcomes weren’t favorable, we drilled into them to find out why. Today it’s recognized that chemotherapy with or without radiation should be delivered to all patients prior to pancreatic cancer surgery. Back in the day, we received a lot of criticism for promoting that clinical concept.”

Looking for a Leadership Role

Life in Houston was good for Dr. Evans and his family. His wife was teaching high school biology, and his children—Courtney, Lindsay, and Bryan—were thriving in academics and sports at Episcopal High School. Although his surgical research career was fulfilling, Dr. Evans was ready for a leadership role, which wasn’t in the wings at the crowded field at MD Anderson. So, in 2009, Dr. Evans and his wife left Houston, and he assumed the position as Chair of the Department of Surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “They had just finished a new cancer center building, and they allowed me to bring the infrastructure of our pancreas program to the chilly north, lock, stock, and barrel. Moreover, the Medical College of Wisconsin had very accomplished physicians in the departments of radiology, interventional gastroenterology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology—all vital for clinical trial development and translational research in pancreatic cancer. I’ve been here for 12 very productive years so far, working with multiple experts in the field and expanding our program on the national level,” said Dr. Evans.

Passion for Surgery

Asked to reflect on his career highlight, Dr. Evans replied, “I’d say my biggest contribution to the Medical College of Wisconsin has been talent development; we have an amazing department of surgery filled with highly accomplished surgeons in nine clinical divisions. I have been fortunate to continue my work in pancreatic cancer research and treatment with a wonderful team of physicians and scientists across many departments. We have completed the world’s first clinical trial of personalized medicine (Susan Tsai, MD) and developed innovative surgical techniques to remove locally advanced pancreatic tumors that involve adjacent blood vessels (Kathleen Christians, MD). I focused on this work early in my career at MD Anderson and have been fortunate to continue it here at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Patients are often referred to me because their tumors were thought to be inoperable, usually after an excellent response to induction therapy. Chemotherapy first for pancreatic cancer has now become routine—something we struggled to accomplish many years ago.”

Along with surgery at least 2 days per week, Dr. Evans sees patients once a week and carries out his administrative duties in a fashion that “puts out fires before they start” in order to maximize his efforts toward creating better outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer. “In order to be effective at this job, it’s important for me to spend a lot of time in the operating room and in the direct care of patients. Optimizing both health-care delivery and the development of innovative clinical trials for pancreatic cancer requires leadership by walking around and staying in touch with all members of the team,” said Dr. Evans.

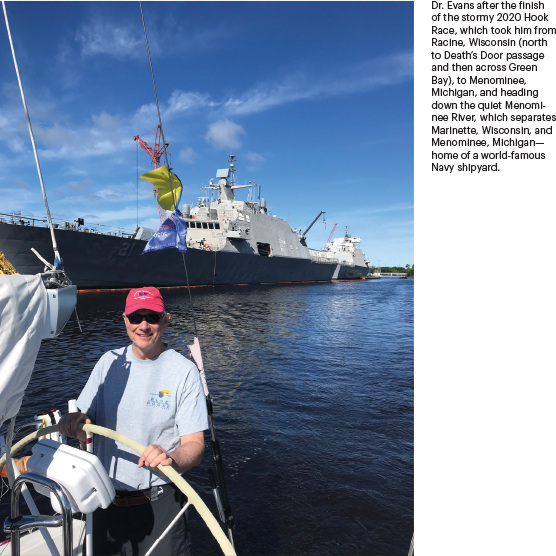

Sailing for Pancreatic Cancer and the Radio Waves

How does a busy surgeon decompress? “When I’m in the operating room or the clinic, I never feel like it’s work; it’s what I love to do. But I played basketball in the Houston YMCA league, which was quite competitive, until my early forties when my knee needed to be reconstructed. However, my wife grew up sailing on Cape Cod, so I became a sailor 20 years ago and now race competitively on Lake Michigan with a yearly appearance in the famed Chicago-to-Mackinac race. We’ve done the Newport-to-Bermuda race once. Our boats are devoted to pancreatic cancer awareness, decked out with purple ribbons.”

While listening to the radio when working on his sailboats, Dr. Evans noted a lack of relevant medical information offered in the regular weekend programming line-up. This realization led him to partner with WISN 1130 AM, a Milwaukee iHeartRadio station, to create a weekly medical information program, “The Word on Medicine.” The first program aired in October 2017, and since then, Dr. Evans and his co-host, Rana Higgins, MD, have spent Saturday afternoons moderating close to 100 unique programs, including a recent 12-part series on the COVID-19 pandemic. The programs have featured more than 300 expert faculty, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants—and, most importantly, patients and their families.