Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS, was born and reared in the sprawling city of Mumbai, the most populous city in India. “My grandmother was a matron in an infectious disease hospital. At that time, smallpox was a serious issue, and the patient care challenges were momentous. She taught me the value of service in caring for the sick. And my father was an administrative officer in a large cancer hospital. Those two influences sparked an early interest in medicine and shaped my belief system significantly. But, in truth, I had equal love for physics and engineering, and the ultimate decision between the physics and engineering arena or medicine was made by the toss of a coin,” said Dr. Badwe.

Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS

A City of Possibilities

Dr. Badwe described Mumbai as a cosmopolitan metropolis with an accepting environment that offered a wide range of opportunities for all of its citizens. “Unlike some other places in India, there was something in Mumbai for everybody no matter what social or economic status one had. And when you create that kind of atmosphere, it allows people to strive for things in life that in other places would seem unattainable,” said Dr. Badwe.

In India, the educational course begins with primary schooling at age 5 and then secondary school from ages 10 to 16, fairly similar to the United States. However, from ages 16 to 18, Indian students begin their preprofessional course, during which they select their college.

Dr. Badwe described his early education as a holistic admixture of teacher-student camaraderie, recalling with fondness the winter months that often began at dawn with an outdoor class assembled around a small bonfire. “We had a fluent experience in that we felt part of nature, with every bit of the natural surroundings teaching you something new and different than what was being taught in books.”

NAME

Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS

TITLE

Director, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai

MEDICAL DEGREES

MBBS, MS, King Edward Memorial Hospital and Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College, Mumbai

NOTABLE HONORS

Lal Bahadur Shastri National Award (2013)

Padma Shri (India’s fourth highest civilian award, for contributions to medicine; 2013)

Indian Nuclear Society Life Time Achievement Award (2010) and Outstanding Service Award (2010)

Joglekar Gold Medal (1993)

Reach to Recovery International Award (1993)

He continued, “At 18, we begin any number of professional courses, which in medicine is 6 years before graduation, then 3 years of working in a primary specialty. If one decides on oncology, it will be another 3 years of study and training. So from age 18, it took me 12 years before I was a certified oncologist.”

According to Dr. Badwe, cancer incidence in India in the early 1980s was so low that the government did not consider it a major health issue. Asked why he decided to pursue a career in oncology, Dr. Badwe said, “Even though oncology at the time was at the low end of desirability for many students—for one, because of its limitations in the mercantile arena—I was brought up in an environment that placed little value on the material aspects of the world. We drew happiness out of the smallest of things. The challenge of trying to conquer a formidable disease such as cancer was also part of the reason I decided on a career in oncology.”

Compassion Is the Significant Other in Care

Dr. Badwe remembered the rigors of the medical training system in India, noting that interacting with individual doctors left a greater impression than systematic book learning. “I remember two of our surgical professors would work in the outpatient cancer clinic from 8 in the morning until after 3 in the afternoon without breaking for lunch. Then they would take us trainees directly to the ward to see patients who’d been under care for the previous week. We’d all be extremely hungry, wondering when the professor was going to call a break for us to eat.”

He continued, “Invariably, one of the patients would be at the point in postoperative care when he could have solid food. I watched the professor get on his knees so his face was level with the patient’s and very affectionately ask if he or she was hungry. In our own minds, we were thinking, please, before this patient eats, we would like some food—that’s how hungry we were. But tending to the patient’s needs first impressed a simple but vital message upon us: half of the care we deliver is medical; the other half is compassion, and without compassion, our care is lopsided.”

“Half of the care we deliver is medical; the other half is compassion, and without compassion, our care is lopsided.”— Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS

Tweet this quote

Dr. Badwe recalled that his surgical professors would remember patients they’d treated years ago by their first names. They would stress the importance of treating the whole patient, not just the disease—a philosophy that he witnessed firsthand as a young trainee.

Global Experience

After completing his 3-year surgical oncology residency at Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai, Dr. Badwe stayed on at the institution and focused on thoracic and breast cancers. In 1989, he spent 6 months at the Toranomon Hospital in Tokyo as a fellow of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus and then relocated to London, where he served as a senior registrar at Guy’s Hospital and as a consultant at the Clinical Research Center, Kings College London School of Medicine, and the Royal Marsden Hospital until 1992.

“After leaving my post at the Royal Marsden, I returned to India and served at Tata Memorial as a consultant in the breast and thoracic services, which continued until 1999,” he recounted. “At that point, I left thoracic surgery and concentrated on breast cancer.”

Dr. Badwe in surgery

Notable History

Dr. Badwe is the current Director of Tata Memorial Hospital, a comprehensive cancer center that was founded in 1941. Every year, nearly 30,000 new patients with cancer visit the institution from all over India and neighboring countries.

“Having a free-standing dedicated cancer center in India in 1941 was very forward-thinking,” he noted, “in that Tata even predated Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), which was established in 1944, prior to which it was the Memorial General Hospital. In fact, Tata was so highly regarded that several surgeons from MSK came here in 1944 to train and interact with surgeons from India.”

He added, “I’m proud to say that the plan of the hospital is to treat the whole spectrum of society. About 30% of our patients with cancer are treated completely free of charge; another 30% pay only 5% of their costs, 20% pay exactly the costs of treatment, and the remaining 20% pay their costs with a 50% to 70% markup.”

“It is the inclusive and collaborative model at Tata that allows our doctors to treat patients and understand disease as it affects people from all societal strata."— Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS

Tweet this quote

In 1957, the Ministry of Health took over the Tata Memorial Hospital, and in 1962, the hospital’s administrative control was transferred to the Department of Atomic Energy. Then in 1966, the hospital and the Cancer Research Institute merged to become the two arms of the Tata Memorial Centre.

“It is the inclusive and collaborative model at Tata that allows our doctors to treat patients and understand disease as it affects people from all societal strata, Dr. Badwe said. “Over the past 2 decades, we have developed at least 5 major interventions that have changed the practice of oncology globally.”

He continued, “We have had two plenary presentations at the ASCO Annual Meetings in consecutive years. The first was on cervical cancer screening [Shastri SS, 2013], and the second was on dissection of neck nodes in head and neck and oral cancers [D’Cruz A, 2015]. The cervical cancer study, which looked at screening using visual inspection with acetic acid, showed a 30% reduction in mortality. States across India have adopted the protocol, which has resulted in a significant reduction in deaths—upward of 22,000 lives saved every year. If implemented in Africa and other places in the developing world, this intervention can save about 75,000 lives per year.”

Happiness Prevents Burnout

Asked about physician burnout, Dr. Badwe responded, “The beginning of burnout is usually unhappiness, and that stems from a choice that an individual exercises. From the moment you think or say that you’ve done too much, you’ve put a limit on your potential and career, and, again, that’s a personal choice.”

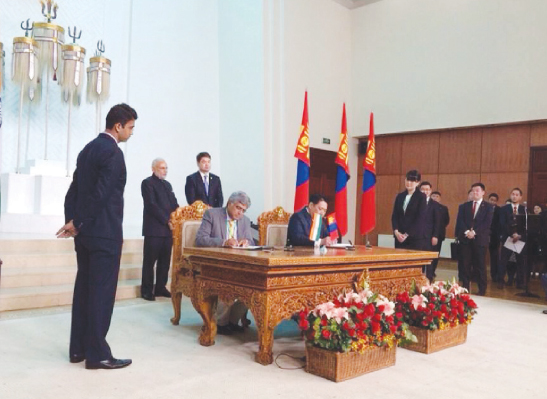

Dr. Badwe signs agreement between the Tata Memorial Centre and the National Cancer Center of Mongolia. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi is standing behind Dr. Badwe and Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj is seated next to Dr. Badwe.

He continued, “About 75,000 new patients with cancer come to Tata Hospital every year. And about 400 residents and 200 faculty care for these patients. So there is a huge amount of work mandated for each doctor. But there is great reward and satisfaction in treating these patients, and one makes the choice to do that or not. There’s a difference between being tired and being burned out. If you’re happy at work, you don’t burn out. If one is working toward one’s irrelevance, the way every medical doctor should, ‘burnout’ is only an imaginary threat.”

The Global Challenge

Dr. Badwe has offered opinions for devising cancer care, disease management, and research protocols worldwide. Considering the emerging burden of cancer in the developing world, he stressed that a concerted effort by leaders in oncology is necessary.

“We need to develop low-cost, easily implementable interventions with proven efficacy that can be widely disseminated throughout low- and middle-income countries,” Dr. Badwe said. “We have, in fact, been studying and initiating these kinds of interventions in India, with quite a bit of success.”

“We need to develop low-cost, easily implementable interventions with proven efficacy that can be widely disseminated throughout low- and middle-income countries.”— Rajendra Achyut Badwe, MBBS, MS

Tweet this quote

He noted that this success is due largely to the National Cancer Grid, which is a network of major cancer centers, research institutes, patient groups, and charitable organizations across India with the mandate of establishing uniform standards of patient care for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. The National Cancer Grid also provides specialized training and education in oncology and facilitates basic translational and clinical research.

“We also have a Web-based program that gives second opinions from the top centers across India to people who don’t have the time or wherewithal to travel. This is a free service,” Dr. Badwe said.

“So some of the key components of our model can be replicated and used in the rest of the developing world,” he said, adding, “If we can improve access to affordable care with better cure rates—and continue to improve—then we are on our way to winning the battle on the global stage.” ■