NAME

Waun Ki Hong, MD, FACP

TITLE

Former Head, Division of Cancer Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

MEDICAL DEGREE

Yonsei University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

NOTABLE HONORS

American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) Margaret Foti Award for Leadership and Extraordinary Achievement in Cancer Research (2016)

American Society of Clinical Oncology Special Recognition Award (2016)

Member of National Cancer Institute’s National Cancer Advisory Board (2008—2014)

Elected Member of National Academy of Medicine (2013)

American Cancer Society Medal of Honor in Clinical Research (2012)

Past President of American Association of Cancer Research (2001–2002)

American Society of Clinical Oncology David Karnofsky Award from ASCO (2000)

American Association of Cancer Research Burchenal Award (2000)

American Association of Cancer Research Rosenthal Award (1993)

Waun Ki Hong, MD, FACP, one of the nation’s leading experts in head and neck and lung cancers, was born in South Korea and grew up in a tiny village outside the nation’s capital of Seoul. Number six of seven siblings, Dr. Hong described his early life in the cozy village as blissful, until the Korean War broke out in 1950, when he was 8 years old.

“It was a horrible experience going from such a peaceful time into war. The North Korean

refugees who were fleeing the fighting would be lined in the streets.”

Prior to the war, Dr. Hong came down with severe abdominal pain. Fluid had built up in his gut as a result of ascites, which became infected with bacterial peritonitis. “I could have died, but I had successful surgery that saved my life. Still, due to complications, I spent about a month in the hospital. As a kid, I received such good care in the hospital that I believe it had a subconscious effect on my respect for the medical profession,” he revealed. “My older brother became an incredible physiologist, and his inspiration along with my experience in the hospital was what eventually influenced my decision to pursue a career in medicine.”

In 1960, after performing well in high school, Dr. Hong entered Yonsei University, College of Engineering and Science, Seoul, where he did his premed studies before entering Yonsei University School of Medicine. He received his medical degree in 1967, after which he served in the South Korean Air Force as a flight surgeon, fulfilling his compulsory national service.

“During the Vietnam War, I was responsible for wounded soldiers we transported from Vietnam to the Philippines or Korea. It was difficult duty caring for wounded soldiers during transport. Many had severe brain trauma or had lost an arm or their legs. Seeing these young men so severely injured was devastating,” admitted Dr. Hong.

A Golden Opportunity

After completing his 3 years of mandatory national service in 1970, Dr. Hong took advantage of what he described as a “golden” opportunity to relocate to America, where he became a rotating intern at Bronx/Lebanon Hospital in New York City.

“After completing my medical training at Bronx/Lebanon, I was fortunate to be accepted to a residency program at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Boston. “I saw so many older veterans at the VA who were suffering from lung and head and neck cancers. Naturally, we didn’t have any effective treatments at the time for these diseases, and that challenge was what inspired me to pursue a career in oncology,” he explained.

I saw so many older veterans at the VA who were suffering from lung and head and neck cancers. Naturally, we didn’t have any effective treatments at the time for these diseases, and that challenge was what inspired me to pursue a career in oncology.— Waun Ki Hong, MD, FACP

Tweet this quote

Dr. Hong described his 2-year residency at the VA as a valuable learning experience, which would later inform his career. In 1973, after completing his residency, Dr. Hong was accepted into a medical oncology fellowship at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. This 2-year fellowship was yet one more valuable learning experience for Dr. Hong.

“After my fellowship, I went back to the Boston VA Medical Center, serving as Chief of Medical Oncology. It was an incredibly rewarding experience. I was the only trained medical oncologist and had to care for so many patients. Moreover, I was responsible for teaching medical students who wanted to pursue a career in oncology and also house staff,” he added.

Dr. Hong acknowledged that being the only trained medical oncologist in a large medical center was extremely challenging, but it also gave him the opportunity to explore the field of oncology within a selected patient population. “I also had the advantage of collaborating with oncologists from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard,” he noted. It was an exciting time in oncology; promising new drugs, such as cisplatin, were coming out of the pipeline. Dr. Hong spent 9 challenging years at Boston’s VA.

“Something I’m proud of during my tenure at the VA was building the hospital’s oncology training program, which ended up being one of the better clinical programs in Boston. By the time I left in 1984, we had produced about 15 board-certified medical oncologists,” he said.

Seminal Trials in Chemoradiation

While at the VA Boston Medical Center, Dr. Hong conducted seminal clinical trials showing that cisplatin-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy was an effective alternative to total laryngectomy for the treatment of cancer of the larynx. “At that time, for people who presented with laryngeal cancer, there was only one treatment: removal of the voice box. I felt very strongly that we could improve the outcome of this disease by enhancing the patient’s quality of life after curative treatment,” said Dr. Hong.

Dr. Hong with his wife, Mihwa, and family

Partnering with Gregory Wolf, MD, Dr. Hong began the VA Cooperative Group for Laryngeal Cancer Study, which in 1991 published results in The New England Journal of Medicine, showing this combination strategy could effectively treat patients while sparing the voice box. The results of his work changed the standard of care in head and neck cancer. This trial also served as a model for organ preservation for many other cancers, such as bladder, breast, and anal.

“At first, there was a lot of pushback from the surgical community,” he admitted, “but we proved that with chemoradiation, we could save the patient’s voice box, which is a tremendous quality-of-life issue.”

Chemoprevention Research at MD Anderson

In 1984, largely because of his seminal work in head and neck cancer, Dr. Hong was recruited by MD Anderson Cancer Center, where he assumed the position of Chief of the Section of Head and Neck Oncology. Dr. Hong made translational research a top priority, pioneering the development of therapeutic and preventive strategies for aerodigestive cancers. “Although research is vital to moving the field forward, I insisted on ensuring that high-quality, compassionate cancer care was the center of my work,” he said.

Dr. Hong continued his chemoprevention research, launching the National Cancer Institute P01 Program Project: Biology and Chemoprevention of Head and Neck Cancer. “We performed two large, randomized, comprehensive clinical trials to identify effective chemopreventive agents,” Dr. Hong explained. He continued: “The project’s goal was to develop effective chemopreventive approaches for reducing the incidence of head and neck cancer, especially in individuals who were at high risk.”

At first, there was a lot of pushback from the surgical community, but we proved that with chemoradiation, we could save the patient’s voice box, which is a tremendous quality-of-life issue.— Waun Ki Hong, MD, FACP

Tweet this quote

Dr. Hong and colleagues are also engaged in another chemoprevention first: the National Cancer Institute study U01: Biochemoprevention Therapy in Advanced Laryngeal Dysplasia, which he called a “very exciting project.” It looked at whether combination chemopreventive agents using retinoids and interferon with vitamin E could induce complete phenotypic reversal.

From 2001 to 2014, Dr. Hong was Head of the Division of Cancer Medicine. “During that period, I had the opportunity to teach and train so many truly outstanding young doctors who aspired to become leaders in the field of oncology. To me, that is such an important contribution, being able to help move the field forward,” he revealed. In 2014 on the occasion of Dr. Hong’s Festschrift, he was honored by Howard H. Koh, MD, then the immediate past U.S. Assistant Secretary for Health. In an excerpt from Dr. Koh’s paper, he recognized some of the many achievements of Dr. Hong,

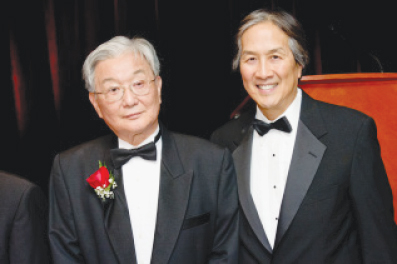

Dr. Hong’s legacy is his colleagues and trainees who now represent the future of cancer medicine in our nation and our world. As Head of Cancer Medicine at MD Anderson, Dr. Hong has overseen 17 academic departments and more than 350 faculty members. He has trained over 200 fellows from 18 countries, including China, Japan, Italy, France, and Spain. And, most notably, he never forgot where he came from. He has given back so much to his homeland. As a result, more than 60 of his trainees are from Korea, with about 20 of them now chairs or directors of cancer centers in Korea.

Howard H. Koh, MD (right) honoring Dr. Hong on the occasion of his Festschrift

Importance of Family and Patients

“I’m not the sort of person who complains about life,” continued Dr. Hong. “You must grab opportunity when it arises. I’m currently semi-retired, but I still work at MD Anderson. I commute between Houston and California, where my two grandchildren live. Family is the most important thing we have.”

His pioneering work in laryngeal cancer changed the treatment paradigm. “To this day, I get e-mails from laryngeal cancer patients, thanking me,” he said.