GUEST EDITOR

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

Dr. Abraham is Professor of Medicine, Lerner College of Medicine, and Chair of the Hematology and Medical Oncology Department at Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic.

In this edition of the Living a Full Life series, guest editor Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, spoke with pioneering art therapist Mickie McGraw, who, through her own experience as a survivor of both polio and cancer, made it her life’s work to share the life-enhancing role of creativity with people who are in some way confined by injury or illness.

To many Americans, the fear and uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic feel as if our society is being transformed in ways we yet don’t fully understand. However, the hesitancy to socialize or congregate in public places is a strange déjà vu for those Americans who lived through the polio epidemic of the past century. At that time, no one knew how the virus was transmitted or its genesis. In 1952, close to 60,000 Americans contracted polio, the highest number since the infectious disease was first discovered, leaving many survivors with some degree of life-long paralysis. In 1955, poliomyelitis was eradicated in the United States by a vaccine developed by Jonas Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh.

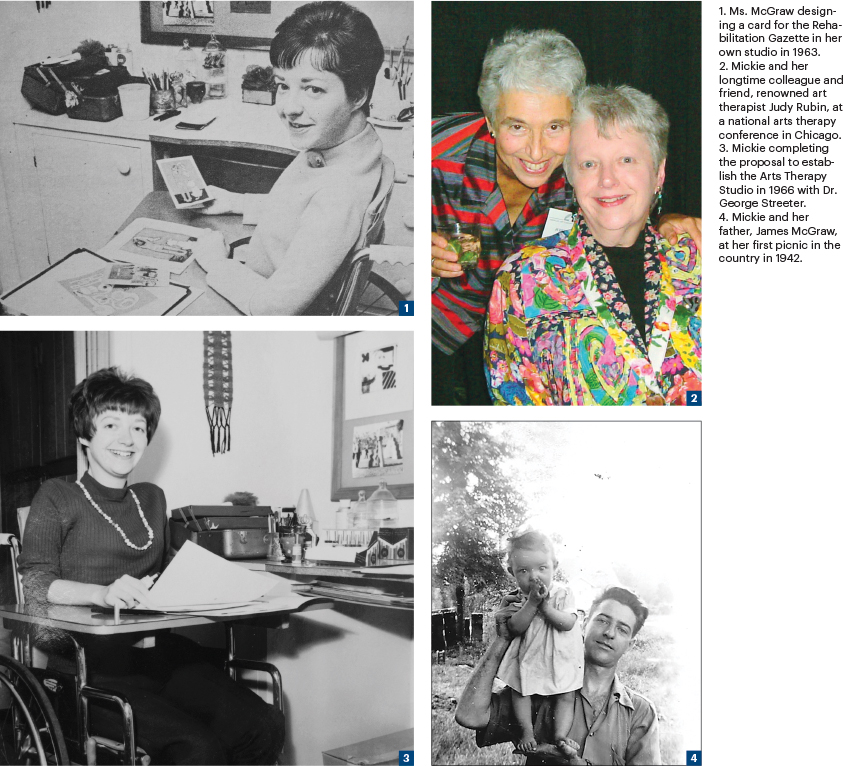

MICKIE McGRAW

On being a polio survivor: “Having polio obviously changed what I did in life, but it never changed me as a person. However, I probably would not have taken the route of art and psychology as a career path had it not been for polio.”

On establishing The Art Therapy Studio: “We opened on a shoestring, about $8,000, which included my salary. Over the years, we grew by using strategic collaborations within the greater Cleveland community and MetroHealth system, and a couple of years ago, we celebrated our 50th anniversary.”

On parallels between the polio epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic: “We were lucky we had President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His compassionate leadership unified the country, as opposed to today, where the country has essentially split on dealing with the current pandemic and how to solve it.”

Summers of Fear

Art therapist Mickie McGraw was born and reared on the east side of Cleveland, a place she still calls home. “I grew up in what would be described as a classic family for the time. My father worked, and my mother was a stay-at-home mom; I had one sister, Sheila, who was then and now my strongest advocate.” Ms. McGraw said. “All in all, it was a very supportive environment.”

In August 1953, when she was 11 years old, she contracted polio. “Even though I was quite young, I was aware of what polio was, as every summer it was covered extensively on the news, and we were not allowed to gather in large groups,” she recalled. “Places like public swimming pools and movie theaters were closed, so we were confined to being with our family and a few close friends.”

Ms. McGraw continued: “I remember a story on TV about a pregnant woman with polio who delivered her baby while in an iron lung. Ironically, I met her the next summer, when I was admitted with polio to City Hospital, which was founded in 1837, just a year after Cleveland became a city. City Hospital was originally an infirmary dedicated to poor, chronically ill people. In 1958, it became a county hospital and was renamed Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital. There were 13 other adults and children admitted onto the polio ward on the same day as I was.”

A Famous Doctor

Ms. McGraw’s doctor was Frederick C. Robbins, MD, a pediatrician and virologist who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with two other researchers, for breakthrough work in isolating and growing the poliovirus in tissue culture. Their research paved the way for the vaccines developed by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin.

By the time the nurses were preparing to put me in the iron lung, I was having difficulty breathing, which was the most terrifying part of the ordeal.— Mickie McGraw

Tweet this quote

When asked about her diagnosis, Ms. McGraw said: “I had a very sore throat and a terrible stiff neck, which my family at first thought was from the flu. On the night before I was diagnosed, I had trouble sitting up in bed and reaching for a glass of water on the night table. I remember thinking to myself, gee, I wonder if I have polio like the people I’ve seen on TV. My mother called our family doctor who came over. By that time, I was having trouble walking, and my father had to carry me to the car and bring me to the hospital.”

The Iron Lung

Directly after being admitted to the hospital, Ms. McGraw was placed in an iron lung, also known as a tank ventilator or Drinker tank, a type of negative pressure ventilator. This mechanical respirator enclosed most of a person’s body and varied the air pressure in the enclosed space, to stimulate breathing.

“By the time the nurses were preparing to put me in the iron lung, I was having difficulty breathing, which was the most terrifying part of the ordeal,” Ms. McGraw said. “However, as I look back, I realize the experience was more terrifying for the adult patients, as they had a better understanding of what lay ahead. As an 11-year-old, I had the belief that my parents could protect me from anything, and that it would all turn out fine,” she added.

Ms. McGraw’s stay in the hospital lasted 13 months, during which she spent 3 months being weaned off of the iron lung. “The first time I went home was on Thanksgiving,” she continued. “Since I was in a wheelchair, my family had to reorganize the house to make it accessible for me. At one point, I was paralyzed from the neck down, which was very difficult to deal with. My family was incredibly supportive, so I was lucky in that regard, as that was not always the case for kids with polio.”

Ms. McGraw recalled the development of the Salk polio vaccine in 1955—2 years after her diagnosis. “On my hospital visits, right after the vaccine came out, some reporters asked me how it felt to have missed out on the vaccine, which I thought was pretty callous. In fact, we were vaccinated but told it would have no effect on our condition; it was intended to prevent infection from another possible strain of the virus,” she noted.

Pioneering Field of Art Therapy

Asked about how polio changed her life, Ms. McGraw responded: “Having polio obviously changed what I did in life, but it never changed me as a person. As a kid, I was very active, a tomboy of sorts. And my home support system gave me confidence in who I was. So even before polio, aspects of my personality had already formed. However, I probably would not have taken the route of art and psychology as a career path had it not been for polio.”

Ms. McGraw was home-schooled through high school. She showed a strong interest and acumen for art. Through the Society for Crippled Children”, now called the Achievement Centers for Children, professional artists volunteered to come to her house and help nurture her blooming artistic talent. As a result, she embarked on an arts-centered life and enrolled in the 5-year Bachelor of Fine Arts program at the Cleveland Institute of Art. “I was the first in my extended family with a college degree,” she declared. “So, in my physical limitations was also a sense of freedom, because I didn’t have the natural distractions to deal with. I was very focused.”

Ms. McGraw majored in graphic arts and she met psychiatrist George Streeter, MD, on the last day of a graphic arts internship at Highland View Hospital, which opened the door to a pioneering field: art therapy. Dr. Streeter had spent 2 years confined to a bed after contracting tuberculosis, and as a lifelong painter, he knew the arts provided a life-affirming activity to those physically confined.

After graduation in 1966, Ms. McGraw met with Dr. Streeter, and together they created what is now the oldest medical art therapy program in the country—The Art Therapy Studio (ATS) at Metro Health Medical Center. “We opened on a shoestring, about $8,000, which included my salary,” she recalled. “Over the years, we grew by using strategic collaborations within the MetroHealth system, and a couple of years ago, we celebrated our 50th anniversary.”

Given her rough start on the way to adulthood, Ms. McGraw could have easily adopted a “why me?” attitude. However, she instead decided that rather than wallow in self-pity, she would go out in the world and make a difference. That can-do philosophy stood her in good stead after she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2009. “Naturally, a cancer diagnosis feels like a punch in the stomach,” she admitted. “It takes your breath away. But I’ve always been a problem-solver, so I asked myself what I could do to beat this and move on. So that’s what I did. That was 10 years ago, and I feel pretty good about the outcome.”

Lessons From the Polio Epidemic

Dr. Abraham asked whether there are any strong comparisons in public mood between the polio epidemic and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Ms. McGraw stated: “I think there were similar reactions among the public, about distancing and large gatherings. But since I was so young at the time, some of the worries did not register as they would for an adult. I do remember picking up some of the fear in the environment every summer. However, there wasn’t the awful economic impact with polio that we see with COVID-19. I also remember the universal rejoicing when the vaccine was discovered.”

Ms. McGraw continued: “We were lucky in my time to have had President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself a polio victim. In that respect, he fought for us with compassionate leadership that unified the country, as opposed to today, where the country has essentially split on its approach and attitudes in dealing with the current pandemic and how to solve it.”

Ms. McGraw shared the following closing thoughts. “You never know what is going to happen tomorrow. We have no health guarantees. My advice is simply to live in the moment but also plan ahead for the days to come with a productive and positive outlook. It will help you cope with things you have no control over.”

DISCLOSURE: Ms. McGraw reported no conflicts of interest.