BOOKMARK

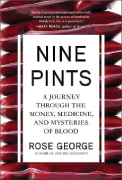

Title: Nine Pints: A Journey Through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood

Author: Rose George

Publisher: Metropolitan Books

Publication date: October 2018

Price: $27.00, hardcover, 368 pages

Blood has been mythologized and misunderstood since the earliest records of humankind and still remains a source of taboo and falsehood in many regions of the world. A new book by English author Rose George, Nine Pints: A Journey Through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood, traverses science and politics, personal stories, global epidemics, ancient history, and the current affairs around blood.

Ms. George begins her book on a personal note: “There is a TV, but I watch my blood. It travels from a needle stuck in the crook of my right elbow, the arm with better veins, into a tube, down into the clear bag…. I am giving almost a pint, and it feels like it always does: soothing and calm.” She deftly uses her experience as a blood donor—a process that happens every 3 seconds around the globe—to segue into a primer on blood.

Blood has been mythologized and misunderstood since the earliest records of humankind and still remains a source of taboo and falsehood in many regions of the world.—

Tweet this quote

The author describes the screening process that ensures the donated blood is safe, free from syphilis, HIV, hepatitis C, malaria, Chagas’ disease, and many more diseases. It is a laborious process that although highly regulated is not perfect, as readers will learn in the chapters exploring the behind-the-scenes activities of England’s National Health Service (NHS) Blood and Transplant.

Readers will be treated to a fascinating tour of the largest European blood donation facility, entering the cooled, pressurized environment that keeps stored plasma free of dust and insects. Ms. George mentions with a bit of chagrin the quasisexist “male plasma donor preference,” enacted in 2003 by England’s NHS, after the rejection of female blood donations due to their hormone-heavy chemistry.

‘Red Market’

Blood is a highly valued commodity in many regions of the world, creating a “red market,” which can get ugly. Ms. George takes readers on a picaresque tour of several in India, which prompted its Supreme Court to ban the sale of blood in 1996. In 2008, acting on a tip, Indian police raided a squalid camp of migrants; a local farmer kept them in sheds, using them as “blood slaves,” bleeding them twice a week. “Some had been imprisoned for more than 2 years. Hemoglobin levels in an adult should be 14 to 18 g/dL of blood. The blood slaves barely had 4 g/dL,” writes Ms. George.

Here readers also get a glimpse of a highly publicized event involving blood: Lance Armstrong’s doping scandal with erythropoietin (EPO). She describes Mr. Armstrong’s fridge full of his own blood, ready to be transfused back into him. The goal was an EPO rush to propel him up mountains to victory.

Leeches and a Heroic Woman

Chapter 2, “The Most Singular and Valuable Reptile,” is equally fascinating. Ms. George brings the reader from tropical ponds into a sterile room of a modern hospital, managed by nurses who are tending to little blood-sucking, slug-like creatures with hundreds of miniature teeth: leeches. As she points out, these creatures that repel us (what’s worse than being called a leech?) are commonly used in flap surgery, to transfer living tissue from one part of the body to another. “Attaching tiny blood vessels calls for a microsurgeon and if the blood vessels get congested, the surgeon calls for a leech. It is an unquestioned practice today.”

Some of the book’s most intense scenes focus on Janet Vaughn—one of the book’s heroes. During World War II, she helped devise and operate systems to deliver life-saving blood to hospitals in ice cream vans during prebombing blackouts. One memorable scene describes Ms. Vaughn injecting blood directly into a wounded girl’s breastbone, because her legs and arms were too severely burned to find veins. Later, the reader discovers that this girl survived and eventually attended the University of Oxford.

A Bloodborne Scare

This tantalizing book is not a memoir, although the author’s personal story is woven throughout, giving the narrative a personal tone, as in Chapter 4, “Blood Borne.” Ms. George was working for a magazine in northern Italy in 1998 when she got a call from an ex-lover; the young man informed her that he had herpes and advised her to get tested for the virus and HIV.

“My stomach dropped…,” she wrote. “I booked a flight to London to get an HIV test. At the time, being positive was a death sentence.” She tested negative, and over the next 15 pages, she looked back to the beginning of the AIDS pandemic. It is a sobering read.

Fighting Taboos

Chapter 7, “Nasty Cloths,” stands out for its quirky adventure into bloodborne territory that readers will marvel at. It begins: “To change his sanitary napkin and clean himself up, Muruga thought the public well near the burial ground was the best option. People avoided the well as they avoided death, and he could remove his pad, rinse his stained clothing, and be safe.”

This is the introduction of a poorly educated workshop helper (known as the “Menstrual Man”) who invents an affordable pad-making system for disenfranchised women. He was a revolutionary in a time and place in India where menstruating women were banned from their homes and forced to sleep in sheds until their period ended. This is a heart-rending tale, illustrating how one dedicated and courageous person can make the world a better, kinder place.

Nine Pints is an extraordinary book. It is highly recommended for readers of The ASCO Post. ■